A couple of months ago, it seemed like things might finally be turning around. After a season of fits and starts -- 9-0 wins soon followed by 4-1 losses; defeating Manchester City, winning 7-1 in the Champions League, and canceling it all out with losses to Leeds and Nottingham Forest -- Liverpool went into the World Cup break with a win over Napoli, a road victory at Spurs and a 3-1 home win against Southampton.

More than anyone, this club needed a break -- and most of their players were going to get one. Outside of Virgil Van Dijk (Netherlands), Jordan Henderson (England), and Darwin Nunez (Uruguay), none of Liverpool's outfield players were expected to start at the World Cup. A number of others -- Thiago, Mohamed Salah, Andy Robertson, Joel Matip, Harvey Elliott, Roberto Firmino, to name a few -- weren't even going to Qatar.

Sure, they'd struggled in the Premier League, but despite that 4-1 defeat to Napoli, Liverpool's 15 points in the Champions League group stages were more than all but two other teams. Plus, it was still the same players and same coaches! Outside of Sadio Mane, everyone was back from last season's record-setting side. And they'd brought in Nunez for a new flavor up front, while the young duo of Elliott and Fabio Carvalho added some youth and some attacking/midfield depth to an aging squad.

Yes, there were injuries but even a depleted version of the squad should've still comfortably settled into somewhere within the top four. Hell, these guys finished third with Nat Phillips and Rhys Williams starting at center-back two years ago.

The first two games back from the World Cup suggested that Liverpool might, in fact, be fine. Even with injuries across the attack, Liverpool dominated matches away to Aston Villa and home to Leicester City. Come the end of the year, they'd won four in a row in the league and were just four points back of fourth.

Well, it's February now, and Liverpool haven't won a Premier League game in 2023. In fact, they've only won a solitary point, have only scored a solitary goal, and have conceded nine times in four matches. Things aren't getting better; it seems like they're only getting worse.

So how bad is it?

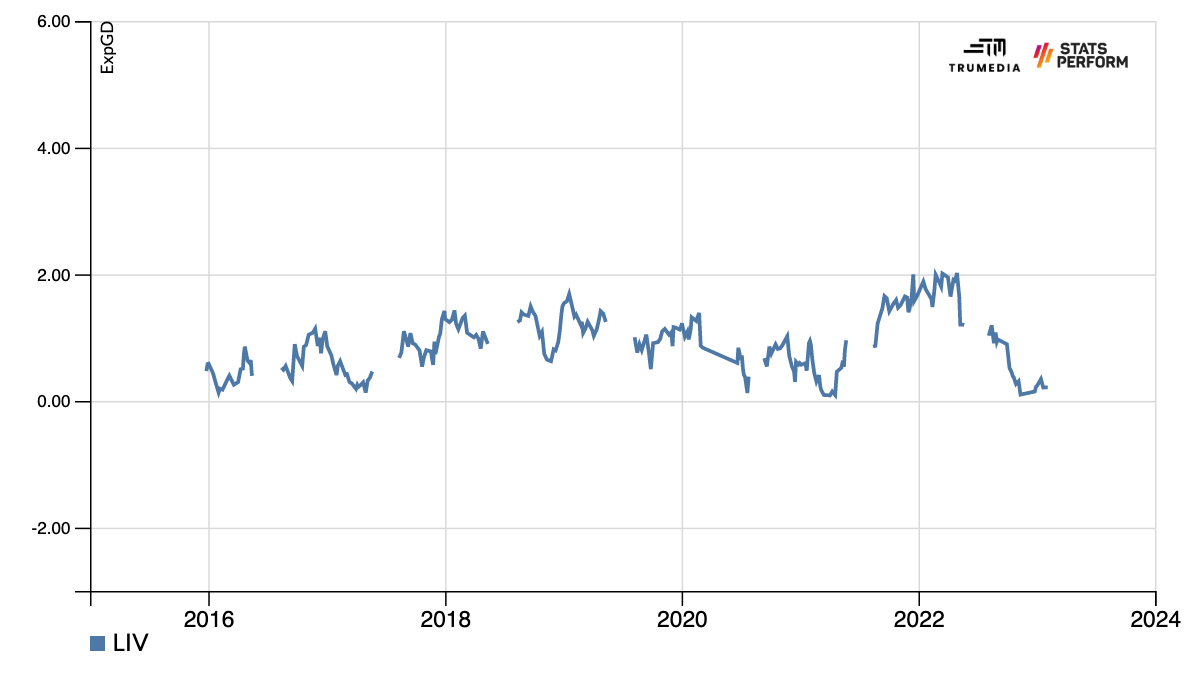

We've been over the injuries, the number of games and the defensive decline already. So perhaps it's useful to take a step back and look at the Jurgen Klopp era as a whole. Since points and goal differential only tell us so much about team quality, let's look at their expected-goal differential in the Premier League for every rolling 10-game stretch since Klopp became manager.

For context, an even xG differential is league average, while anything plus-1 or above means you're one of the best teams on the planet.

There's a break between each season, and you can see that in five of Klopp's six full seasons: The team's form tends to peak right around the middle of the season, and tails off in the second half. I'd caution against reading too much into this, as the competitive value of later-in-the-season matches changes based on where you are in the table and how deep of a run you're making in Europe, but the trend does at least lend a little credence to the idea that Klopp's teams require a tough-to-maintain level of physical and emotional output. Maybe the players can keep up for 19 or 20 games, but then start to tire as the matches add up.

Of course, that didn't happen last season, which -- as the graph shows -- was Liverpool's best year of the Klopp era. Their average 10-game stretch was equal to the peak of any of the previous six seasons: midway through the 2018-19 season. There still was a falloff in 2021-22, but it didn't happen until the last month of the season. They were heavily rotating the team amid the concurrent runs to the FA Cup and Champions League finals, but there were at least some warning signs of decline before the start of this season.

Now, Liverpool have been this bad before. They dipped down to a similar point at the end of Klopp's first full season, when they crawled over the finish line and finished just one point ahead of fifth-place Arsenal to qualify for the Champions League. It happened again in 2019-20, after the coronavirus break and after they'd already clinched the league title. It happened again the following season, right around a similar point in the calendar to the current chaos.

On March 10, 2021, Liverpool were in eighth place, seven points back of fourth. Per FiveThirtyEight, they had a 20% chance of qualifying for the Champions League at the time. Today, they're in 10th, 11 points back of fourth, and FiveThirtyEight gives them a 15% chance of qualifying for the Champions League.

The good news, then: Every time they've hit a similar point in the past, they've bounced right back up.

Steve Nicol reacts to Liverpool's 3-0 defeat at the hands of Wolverhapton at the Molineux Stadium.

Will it get better?

Here comes the bad news: This time, it's different.

First, the team. In 2016-17, the squad's average age (weighted by minutes played) was 26.1 -- the third youngest in the league, per FBref. Then, in 2020-21, it had moved up to 26.8 -- the sixth oldest in the league. And now it's 28.2 -- the fourth oldest in the league.

The ranking, though, is less important than the actual number.

The last two times Liverpool's performances reached a similarly mediocre level, the squad was composed mainly of players right in the middle of their primes. A team-wide decline in performance, both times, could be explained away as just an aberration or the result of uncontrollable and fleeting external factors; there was no reason these groups of players should suddenly decline. But this season? Well, the average player on the field for Liverpool this season is already past his prime years, which typically come in the 24 to 28 range.

When a bunch of players get slightly worse, it adds up.

The other big difference: how the team is being built.

To aid the Champions League push, forward Sadio Mane, midfielder Georginio Wijnaldum and defender Joel Matip joined the club in the summer of 2016. After the just-barely-got-there end to the 2016-17 season, Liverpool responded by signing forward Mohamed Salah, midfielder Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain and defender Andy Robertson in the summer, followed by star defender Virgil van Dijk in the winter. They also transferred Brazilian playmaker Philippe Coutinho to Barcelona in January for a club record £105 million fee. And in the following window, they added goalkeeper Alisson plus midfielder Fabinho, Naby Keita and Xherdan Shaqiri.

So, in about 24 months, the club added the starting keeper, starting left-back, both starting center-backs, two starting midfielders, and two starting forwards for a team that would go on to win the Champions League and take home 99 points in the Premier League in consecutive seasons. That's about the hottest run of recruiting you'll ever see.

There were free transfers (Matip), deals for players on relegated teams (Wijnaldum and Robertson), moves for undervalued star attackers with fantastic underlying numbers (Mane and Salah), out-of-nowhere deals wrapped up right after losing the Champions League final (Fabinho), and risky big-money moves for big names who ended up being even better than expected (Alisson and van Dijk). Meanwhile, just about every player Liverpool let go over that stretch -- Coutinho, goalkeeper Danny Ward, defender Mamadou Sakho and forwards Dominic Solanke, Christian Benteke and Jordon Ibe -- failed to live up their transfer fees.

While Fenway Sports Group are seemingly hated by a loud, not insubstantial portion of the fanbase, Liverpool were simply the best-run big club in world soccer. They finished third in the most-recent Deloitte Money League rankings, meaning that for the 201-22 season, they made more money than every club in Europe other than Manchester City and Real Madrid. But the biggest driver of increased revenue is still on-field success, and as recently as -- you guessed it -- 2016-17 Liverpool only brought in the fifth-highest revenues ... in England. They closed that gap and then leapt over it by making smart player acquisitions, year after year after year.

With all that revenue now and this smart decision-making apparatus in place, then shouldn't they be poised to rebuild this thing -- even if this season doesn't end with a top-four or a Champions League run? Well, it's unclear how much of that apparatus remains.

Among Europe's big clubs, Liverpool were the real first-movers in terms of adopting analytical decision-making. Every club has analysts; few of them listen to them. Liverpool, though, were being run by the analysts. Michael Edwards, the club's Sporting Director, came over from Tottenham, where he was a performance analyst. Ian Graham, who has a PhD in theoretical physics from Cambridge, served as the Head of Research. There was also lead data scientist Will Spearman, who worked at the European Organisation for Nuclear Research before joining Liverpool. As Graham described their work to The New York Times Magazine, "We're just starting to ask the question, 'Why don't we try to play football in a slightly different way?'"

More important than revolutionizing the game, though, was building a functional organization. Liverpool hired Klopp on the back of a disappointing final season with Borussia Dortmund, but they weren't scared away by the poor results because their data department knew that Dortmund had just experienced a season-long stretch of terrible finishing luck. "They're the reason I'm here," Klopp said, of Graham's group.

So rather than a bunch of nerds working away in a dark room or a manager constantly feuding with the front office, Liverpool had the most sophisticated analytical front office in the sport working directly with one of the best coaches in the sport. Klopp knew what kinds of players would work for his system, but the front office could, reportedly, talk him into signing Mohamed Salah instead of Julian Brandt for the third spot in the front three. In turn, Klopp could take the occasionally ill-fitting pieces that the front office would find and make it work: Roberto Firmino as a false nine, anyone?

As detailed by Melissa Reddy for Sky Sports, Klopp and Edwards worked closely together, along with Mike Gordon, the president of FSG. In other words: ownership, the front office and the coaching staff were constantly in contact with each other. This led to things like Trent Alexander-Arnold being developed into a right back because it best-fit the club's long-term squad goals. It's also why you almost never heard of Liverpool's transfer moves until they happened. Outside of the move for Van Dijk, there were no sagas or bids being prepared; just Diogo Jota and Thiago suddenly being announced as Liverpool players. It almost always felt like the club were a few steps ahead of everyone else.

Not anymore -- or at least not right now.

Edwards, whose LinkedIn page lists his current occupation as "On a break", left the club after last season, but was replaced by his no. 2, Julian Ward. Nothing else changed, at least for a couple months. First, news broke in November that FSG were looking to sell the club. Soon after that, both Ward and Graham told the club they would also be leaving after the season.

It appears that Gordon is now spending most of his time on the sale process rather than the, you know, "help the soccer team win soccer games" part of the gig. With Edwards gone and Gordon essentially out of the picture, Liverpool are looking a lot more like all of the other inefficient teams across the continent, with the coaching staff driving transfer business.

In November, my colleague Mark Ogden reported that Klopp would assume a larger role in transfer dealings and you can already see it, too. Nunez was unlike any of the team's previous transfers: a raw, unproven and very expensive player at the most expensive position in the sport. The same goes for Cody Gakpo, a physically impressive forward who scored three goals on five shots at the World Cup.

That's not to say that neither one will work out -- and Nunez certainly seems like he's going to be a hit, eventually -- but these players both seems like the kind of player a coaching staff would recruit: all kinds of physical potential, with couple high-profile moments (for Nunez in the Champions League, Gakpo at the World Cup).

Coaches love the idea of molding talent; they don't have the time to watch as many games as a statistical model can, and they're less concerned with value than with talent. Same goes for the club's reported pursuit of Jude Bellingham, who would likely be the most expensive midfielder in the history of the sport. In the past, Liverpool seem like they would have found two or three key contributors for the combined cost of one Bellingham.

So where does it all go from here?

It still feels like Liverpool have too much talent -- even with the aging and the injuries -- to be this bad. They still should bounce back at some point, and a Champions League run wouldn't surprise anyone. But the longer-term future is less clear.

One source I spoke to who works with European clubs sees two futures for the team: 1) FSG will sell the club outright soon. Or 2) They'll sell a minority stake, bring their attention back to the club, attempt to run back another cycle of success, and then try to sell the club again in another five years or so.

For now, though, Liverpool remain stuck in a new kind of netherworld: plenty of resources, plenty of talent, but no longer any real plan.