Remember the last time Chelsea and Liverpool played? No? Well, it feels like it was six years ago.

Back in May, they met in the FA Cup final, just a couple of months after meeting in the Carabao Cup final. The latter ended scoreless in penalties, and so did the former; their league matches would have gone to penalties too, were it possible. Their second league fixture was a thrilling 2-2 draw at Stamford Bridge, while their early-season matchup at Anfield ended 1-1, with the Blues holding the Reds mostly at arm's length after Reece James was sent off right before halftime.

After winning the Carabao Cup, Liverpool won the FA Cup. For Jurgen Klopp's team, it ended up salvaging the bare minimum of success from their lights-out, season-long performance. Despite reaching the final of all three cups and running Manchester City all the way into the second half of the final game of the season, they only won the lesser two of the four major trophies. In an oh-so-slightly-alternate universe, two bounces go differently, Liverpool also win the Champions and Premier leagues, and there's a legit argument for them as the best English team of all time.

For Chelsea last season, there's at least an argument for them as one of the best English teams to win nothing. Their plus-43 goal differential was a top-35 mark in league history. Thomas Tuchel & Co. beat Real Madrid 3-1 at the Bernabeu to force extra time in the Champions League quarterfinals. On the whole, they outplayed the eventual champions ... though you could say the same thing about City and Liverpool, too. Plus, they played Liverpool to a stalemate in two cup finals, only to come away empty-handed from the lottery that is two penalty shootouts.

Despite two seasons that ended in disappointment, each club still had one of the five best managers in the world. Chelsea won the Champions League just a year earlier, while Liverpool somehow had managed to improve on the team that won 99 points. With deep, proven squads and brilliant coaching, they each entered this season as top-five teams in the world.

Now, they each enter Saturday's matchup at Anfield barely clinging to a top-10 spot in their own league. Liverpool sit ninth, Chelsea 10th. Even though it's mostly the same players who've been excellent in the past, both sides have been unthinkably terrible so far this season. What the heck happened? Maybe they just played too many games.

Liverpool's disappearing defense

The most oversimplified version of the Klopp-at-Liverpool story goes like this:

Klopp arrives. The attack is immediately very good, but the defense keeps buckling under the weight of Liverpool's own press. Then Sadio Mane and Mohamed Salah show up, and the attack becomes world-class. The defense continues to shake until the Reds sign Virgil van Dijk, Alisson and Fabinho in the same year. All of a sudden, the defense becomes world-class, too, and then Liverpool win every possible trophy over a four-year stretch.

- Stream on ESPN+: LaLiga, Bundesliga, more (U.S.)

Over Klopp's 275 Premier League games as manager, Liverpool have allowed 266 goals -- just slightly below a goal per game. Their three best seasons -- the Champions League-winning 2018-19 campaign, the 99 points of 2019-20, and the all-fronts excellence of last season -- were the three seasons when they allowed under a goal per game:

2018-19: 0.6 goals allowed

2019-20: 0.9 goals allowed

2021-22: 0.6 goals allowed

This season, they're scoring 1.9 goals per game -- lower than the Klopp era average of 2.1 and lower than any full-season mark other than 2020-21. However, they're generating 1.8 expected goals per game -- right around the Klopp-era average of 1.9, and the same as they averaged in the 2019-20 and 2020-21 seasons. Only Arsenal and Manchester City have been better at creating chances this season, and given that Mohamed Salah is the only Liverpool attacker to start more than 11 league games so far, there's reason to believe the attack can still improve.

The same can be said about the defense because, well, it can't really get any worse, can it? Liverpool are allowing 1.4 goals per game, which is tied with Brighton for just eighth-best in the league. It might be even worse than that, though: Liverpool are allowing 1.5 expected goals per game, which is the 14th-best mark in the league and 50% worse than the Klopp era average.

And it could be even worse than that.

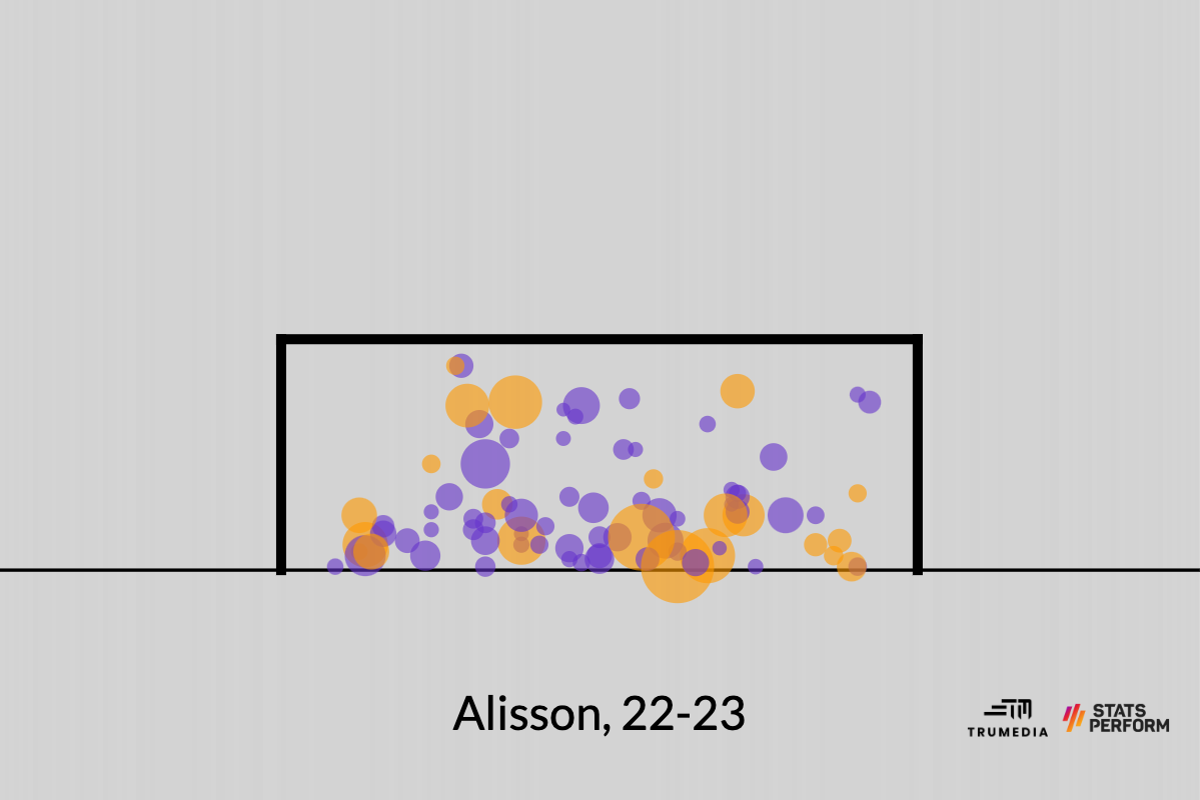

Opponents have been picking out corners left and right against Liverpool this season. They've conceded 26.17 xG this season, but when you control for where the shot ended up on the goal frame, that number rises to 32.42 -- the second-highest mark in the league. Alisson, however, has conceded only 24 goals from opposition shots, which means he has saved 8.42 goals above average -- by far the best mark in the league. Orange circles are goals, purple are saves; the bigger the circle, the higher the xG value of the attempt:

Put another way, Alisson is playing like the best keeper in the world and Liverpool still have only a league-average defense, at best. They're allowing 10.4 shots per game -- by far the most of the Klopp era -- but still just the fourth-fewest in the league. However, the value of those shots (0.141 xG per shot) is not only the highest of the Klopp era but the highest in the league this season.

It all looks bad, really. They're allowing 21.9 opponent touches in the penalty area -- the most of the Klopp era and just the sixth-fewest in the league. Their pressing rate (measured by "passes allowed per defensive action" or PPDA) is the least intense of the Klopp era: 12.40, just seventh most aggressive in the league. And it's the same story with their share of final-third possession: 60.7%, lowest of the Klopp era, though third-highest in the league this season.

So, Liverpool are conceding better chances than ever before, conceding more chances than ever before, letting their opponents in the penalty area more often than ever before and allowing their opponents to have more of the ball than ever before.

Compared with the previous six seasons, it's a nightmare.

Unless you ask Chelsea...

While Liverpool have been terrible, they still have the sixth-best goal differential and the fifth-best xG differential in the league. That's a massive drop-off from where they were last year -- fifth-best goal differential in league history, with underlying numbers to match -- but they're also somewhat unlucky to be down in ninth.

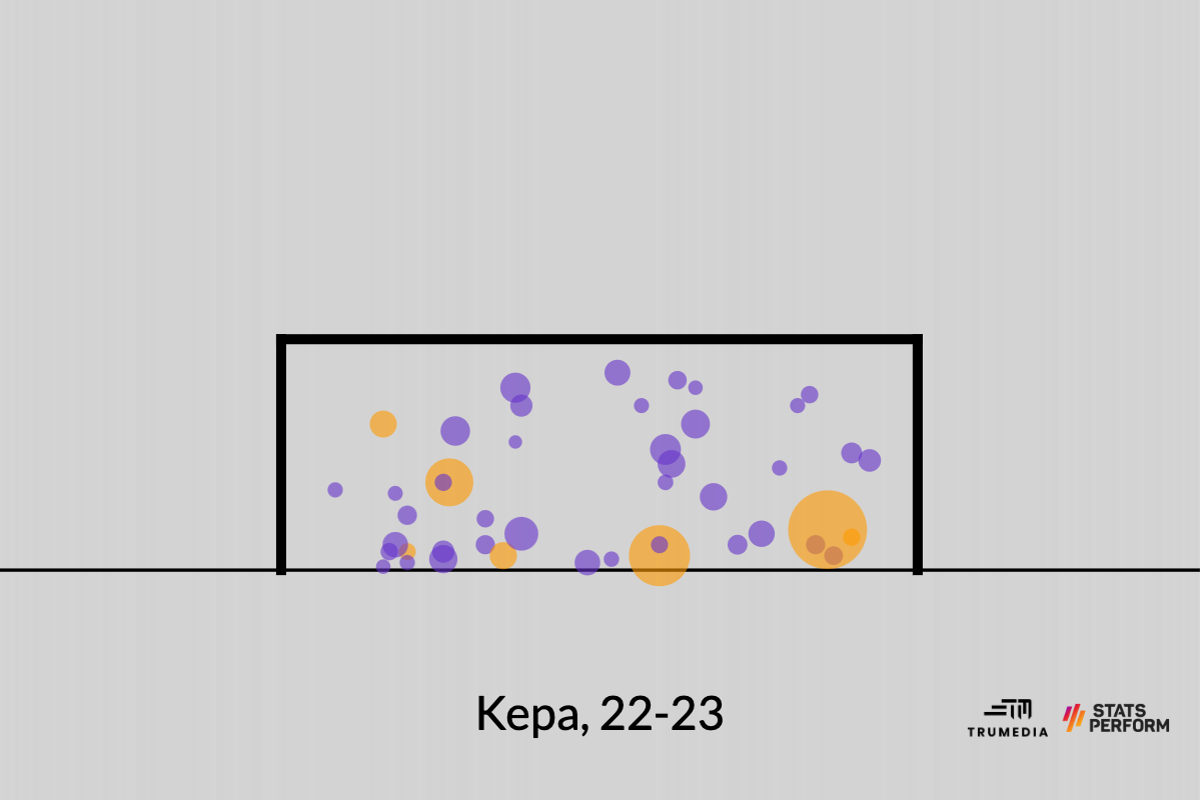

Chelsea, meanwhile, belong in 10th place. They have the 10th-best goal and xG differential. Much as with Liverpool, though, it really could be even worse. Much-maligned Kepa has saved 6.3 goals above average -- second in the league behind Alisson.

Liverpool's high-variance approach has landed them in ninth, while Chelsea frequently feel like a team that's trying to turn every match into a coin flip -- or can't do any better.

Under Tuchel, they became an elite defensive team by limiting both shots and shot quality. Part of the reason they were able to do that was a deliberate approach in possession that didn't expose them if they lost the ball but also created high-quality chances from a smaller number of shots than you'd expect from a Champions League-winning team.

This season, Tuchel has gone, the high-quality shots are gone and the defense has declined, too. Chelsea press aggressively, but they don't quickly turn the press into shots. Rather, the press just seems to deflate the game. Despite averaging 58% of the ball -- third after City and Liverpool -- they're turning that into only the 11th-most shots (11.6) and the sixth-fewest shots allowed (11.1). They can't create chances from all of the possession, but it's also really not helping them prevent chances, either.

Last week, I wrote about how Chelsea had signed a baffling 12 new players since part-owner Todd Boehly had taken over as interim sporting director last summer. They've signed two more players since that piece was published. None of the new arrivals has helped improve the team, while almost all of the players who were already there -- the ones we've seen play, together, at an elite level before -- seem to have gotten worse, too.

So... why?

The betting market Sporting Index updates the expected point totals of all the teams in the Premier League throughout the season. Before any games were played, Liverpool were projected to finish with 86 points -- second behind City (90) and well ahead of Tottenham (72) in third. Chelsea were fourth with 70 -- two more than Arsenal in fifth.

After 18 matches, Liverpool's projected point total has plummeted to 68. That 18-point swing is the biggest change relative to preseason expectations, in either direction. The second biggest drop-off is West Ham (14 points), and then there's Chelsea (nine points, down to 62) tied with Everton for the third-biggest decline in expectation.

There's no one reason for either decline. Both teams were among the oldest teams in the league last season: Liverpool with the fourth-oldest average age (27.7) weighted by minutes played, while Chelsea were the sixth-oldest (27.4). And they've only gotten older this season: Liverpool are up to 28.3 and Chelsea up to 27.9. Plus, both teams operated on very thin margins in very different ways.

Liverpool pressed super aggressively, threw their fullbacks forward and even asked two of their three central midfielders to contribute around the penalty area. When everything is clicking, you're creating high-quality chances nonstop, keeping the ball away from your goal and then snuffing out the handful of dangerous attacks that enter into your defensive third. But if everyone gets slightly older, the pressing from the front can get slightly worse, the midfield can be slightly slower to gobble up loose balls that break through and the defenders can be slightly less effective at covering up all that space on conceded counters ... perhaps it adds up to an exponential decline.

With Chelsea, they were able to exert so much control over matches because they didn't attempt as many shots, while their patient possession play allowed them to find the right openings and create higher-than-average-quality opportunities without risking the same number of bodies forward that, say, Liverpool did. But that only works if your attackers are executing at an incredibly high level and constantly make the right decisions about when to attack and when to just keep the ball. If the execution drops off at all, then maybe the output declines significantly.

That all seems as if it's playing a role, but a simpler explanation might be that both teams are running on fumes.

Over the past two years, Chelsea have played 122 competitive games -- more than any other team in Europe. (Liverpool are third with 117.) And since the start of last season, Liverpool lead the way with 92. Chelsea are second with 90, and then there's Manchester City (87), who haven't quite hit the same heights as previous seasons, followed by West Ham (85), the only Premier League team that might be having a more disappointing season than Liverpool or Chelsea. The other two English sides with 80-plus competitive matches on the ledger since the start of last season: Leicester City, who are two points clear of the relegation zone, and Tottenham, who have a worse goal differential than Liverpool despite having played two more matches.

How direct the cause is, I don't know, but most of the teams that are disappointing this season have played a ton of games over the past year and a half.

It seems to work in the opposite direction, too. Arsenal, who are currently 17 points ahead of their preseason Sporting Index projection, have played 71 competitive matches since the start of last season; both Liverpool and Chelsea have basically played an extra half-season of matches over the same period of time. Newcastle, who are 14 points ahead of their preseason projection, are even fresher. They've played just 64 games since the 2021-22 season began -- fewer matches than any team currently in the Premier League other than Aston Villa (63).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Arsenal and Newcastle have been able to rely on a small core of players as they've risen up the table. The former have 10 players who have played at least 75% of the league minutes, and the latter have 11. Liverpool and Chelsea, meanwhile, have been fighting through injuries all season; just five guys for Liverpool and three for Chelsea have broken that same 75% mark. Soccer players typically get injured playing soccer games, and when you're playing more games, you're more likely to get injured.

Of course, it's not as if the two clubs were unaware of how many games they'd played before this season or how many games they'd be playing this season. Modern players at the top end of the pyramid play too many games, but if you want to win as many games as you can, you have to acknowledge that reality rather than ignoring it and hoping for the best.

Chelsea brought in a full team and subs bench of new players, and although Liverpool's midfield depth is somewhat thin, they have multiple theoretically good players at almost every other position on the field. Neither Klopp nor Tuchel -- nor his replacement, Graham Potter -- has done a particularly good job at managing the respective situations. Even with aging squads and injuries and tired legs, both of these teams should still be way better than they are.

And they both will be, I think. (Then again, I've thought that since September, and it still hasn't happened.) The talent in both squads is too impressive -- and, at least in Liverpool's case, their manager's track record is about as good as it gets. But if they're going to turn it around this season, it sure seems as if they're both going to have to do something different. Their players haven't had the juice to play the way they used to play, and that's not going to change.

As bad as it seems, it's only January; we still have four months to go.