If you want to sound like a smart soccer fan, here's your word: gegenpressing. If you don't want to alienate your friends and loved ones, then perhaps peel back the accent and just go with: pressing or even counter-pressing.

Whatever language you land on, the broader concept is the defining feature of the modern version of the world's most popular sport. For the majority of the sport's history, the most important player was the No. 10 -- the attacking midfielder who would be positioned at the top of the penalty area, between the opposition defensive and midfield lines, and play balls into the penalty area or score the goals himself. These are the geniuses, the artists, the players who'd frequently be referred to in magical terms: Pele, Maradona, Zinedine Zidane and Ronaldinho all wore 10.

Eventually, though, as clubs became modernized, started raking in hundreds of millions of dollars in annual revenue, and thus grew their coaching and analysis staffs, they got really good at destroying the magic. In response to the dominance of the No.10, coaches simply began to pack extra players into the areas where the attacking midfielders once flourished. The position is now all but extinct.

What followed was a brief period where most of the best teams in the world were reactive and destructive. Jorge Valdano, a teammate of Maradona on the World Cup-winning Argentina side in 1986, famously described a match between English sides Liverpool and Chelsea as such: "Put a s--- hanging from a stick in the middle of this passionate, crazy stadium and there are people who will tell you it's a work of art. It's not: it's a s--- hanging from a stick".

Thankfully, that, uh, "era" was quickly overtaken by the "Pressing Era. The best teams now push all their defenders high up the field and try to win the ball back in the attacking third. While there was no space at the top of box for the creative geniuses anymore, these teams created all kinds of new spaces for themselves by swarming their opponents as soon as they lost the ball, winning it back, and attacking the gaps in the now-unsettled defense. "No playmaker in the world can be as good as a good counter-pressing situation," according to Liverpool manager Jurgen Klopp.

The major stylistic lever -- the pre-planned strategy that most affects what you see in a given game on a given Saturday -- is the press: how aggressive both teams are in trying to win the ball back, and how successful they are at doing so.

Got it? OK, now forget it all, because the first step toward understanding what you're about to see in Qatar is accepting that it's going to look very different from the soccer you might've seen over the past four years.

Why not press?

Although Cristiano Ronaldo recently claimed to have never heard of him, there's perhaps no single person who's had more of an impact on the modern game than a tiny, bespectacled German nerd named Ralf Rangnick.

While managing at then-third-division club Hoffenheim back in 2006, Rangnick came across a piece of research that suggested goals are most often scored within eight seconds of winning possession back from your opponent. Eight years prior, while coaching a tiny club called Ulm, Rangnick had appeared on a national talkshow called Das aktuelle Sportstudio. Among other things, he suggested that teams could be more proactive in attempting to win the ball back from their opponents. By saying this on national TV in a massively successful and very traditional soccer-playing nation, Rangnick earned the mocking nickname of "football professor."

However, there was a virtuous connection between the two ideas. Rangnick became convinced that his teams should pressure the ball high up the field and then attempt low-probability passes quickly toward the opposition goal because if those passes failed, they could just start the cycle up again. "We are prepared to play risky passes, at the danger of them going astray, because that opens up the possibility to attack the second ball," he's said.

- World Cup 2022: Schedule, how to watch

Fully committed to these ideas, Hoffenheim quickly were promoted through the lower leagues and up to the Bundesliga, Germany's first division.

Swayed by his style, Red Bull -- yes, that Red Bull -- gave Rangnick the keys to their soccer project, and he helped to define the style for what would become their network of clubs across the globe: lots of energy, forward passing and chasing after loose balls. It's mostly worked because Red Bull are able to recruit across the world and find players who fit their ideas, and are then trained toward them through their network of teams. The same goes for all of the big clubs across Europe that have adopted their own version of the press: They can sign whoever they want and then coach them up, day after day after day.

Sam Borden joins Futbol Americas to talk the USMNT captaincy situation as well as the latest on injury news.

You know who can't just sign anyone and who doesn't get to train every week? National teams. For even the best national teams, the player pool is constantly changing, and the teams only get together a few times per year to train.

When I asked him about the occasional high-profile breakdowns that come from playing an aggressive high-press, current Leeds manager and former Red Bull coach Jesse Marsch said: "Most of those times that it looks bad is a tactical breakdown where the players behind the ball, when we lose a ball, are not in tactically sound positions. Then the game looks more open than it should be. It's aggressive. There's no doubt, but it's also intelligent. The goal is to not be wild; the goal is to still be in control."

To play an aggressive press, the players need to have the physical capacity, and then they need to know how to move in concert with one another. Otherwise, a couple of simple passes and boom: The other team is in on goal. Unfortunately, international sides don't get to pick who was born where, and they really just don't have the training time necessary to play in such an aggressive way without constantly getting torn to shreds.

- World Cup rank: The top 50 players in Qatar

France are the defending champs and the current third-favorites to win the whole thing, according to the betting markets. Brazil, meanwhile, are the favorites. According to a collection of projections combined together by Jan Van Haaren, a data scientist for a Champions League club in Belgium, Neymar & Co. have a 20% chance of winning the whole thing, while no one else is above 10%. In all competitive matches played since the beginning of last August, Brazil have allowed their opponents to complete 83% of their passes. Only two teams in the World Cup field were easier to pass against: Costa Rica ... and France.

That doesn't mean everyone is going to abandon the press, though. Since last August, Germany have won possession 7.4 times per game in the final-third -- second among all 32 teams, behind just Japan. In addition to those two, a pair of other teams have both held their opponents to a completion percentage of 75% or lower and won at least six possessions per game in the attacking third: Spain and the United States.

In the club game, the full-season success rate of pressing makes it a good risk-reward bet in the long run. But at the World Cup, you play no more than seven games, and the risk of a leaky press is way higher. So, the defining strategic facet of modern soccer I talked about in the intro? It'll mostly be absent from its most popular modern event.

So what will we get instead?

On soccer's journey toward analytical enlightenment, the sport has gotten really good at measuring what happens around the goal.

Throughout the World Cup, you'll no doubt hear "expected goals" mentioned. Abbreviated as xG, it's just an estimated probability that a given chance will be converted based on a number of historical characteristics. For example, a tap-in on the goal line would be worth something like 0.99 expected goals (99%) because Eric Choupo-Moting exists:

Meanwhile, a shot from 50 yards out would be worth something like 0.01 xG. And then there's everything in between. Why do we care about this? Well, xG is more predictive of future performance than any other single statistic. In the short term, anyone can turn two or three low-probability shots into goals, but in the long run, the best teams are the ones that create lots of high-quality chances and concede very few of them.

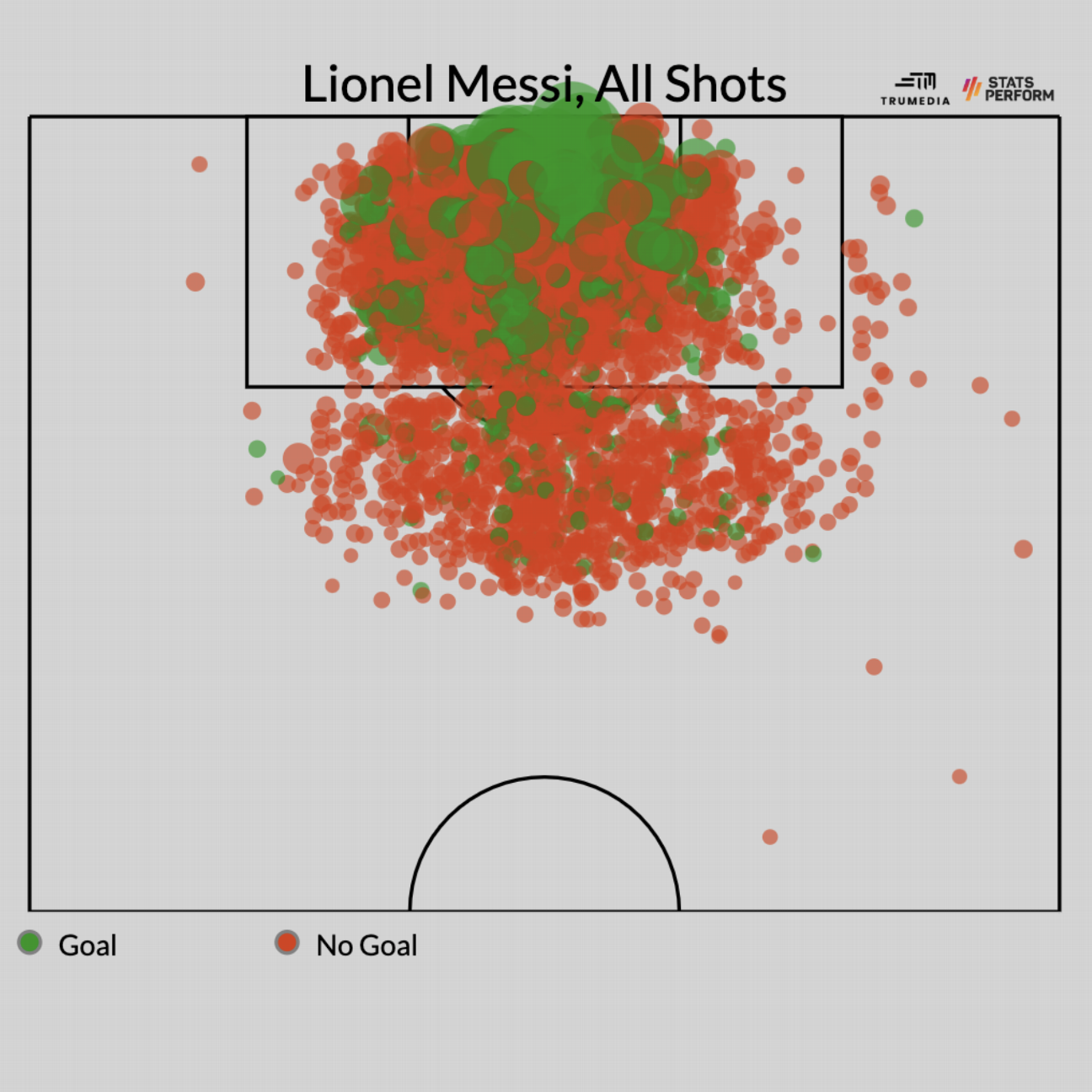

On an individual level, though, the same thinking applies. The best goal-scorers are the ones who get on the end of the largest collection of great chances, not the ones who are most likely to turn a particular shot into a goal. Lionel Messi actually is better than everyone else at converting shots into goals, but per Stats Perform data going back to 2010, he's scored 533 goals in competitive club games over that stretch from chances worth about 435 expected goals. In other words, more than 80% of his scoring can be predicted from a number of factors recorded before he ever kicks a ball:

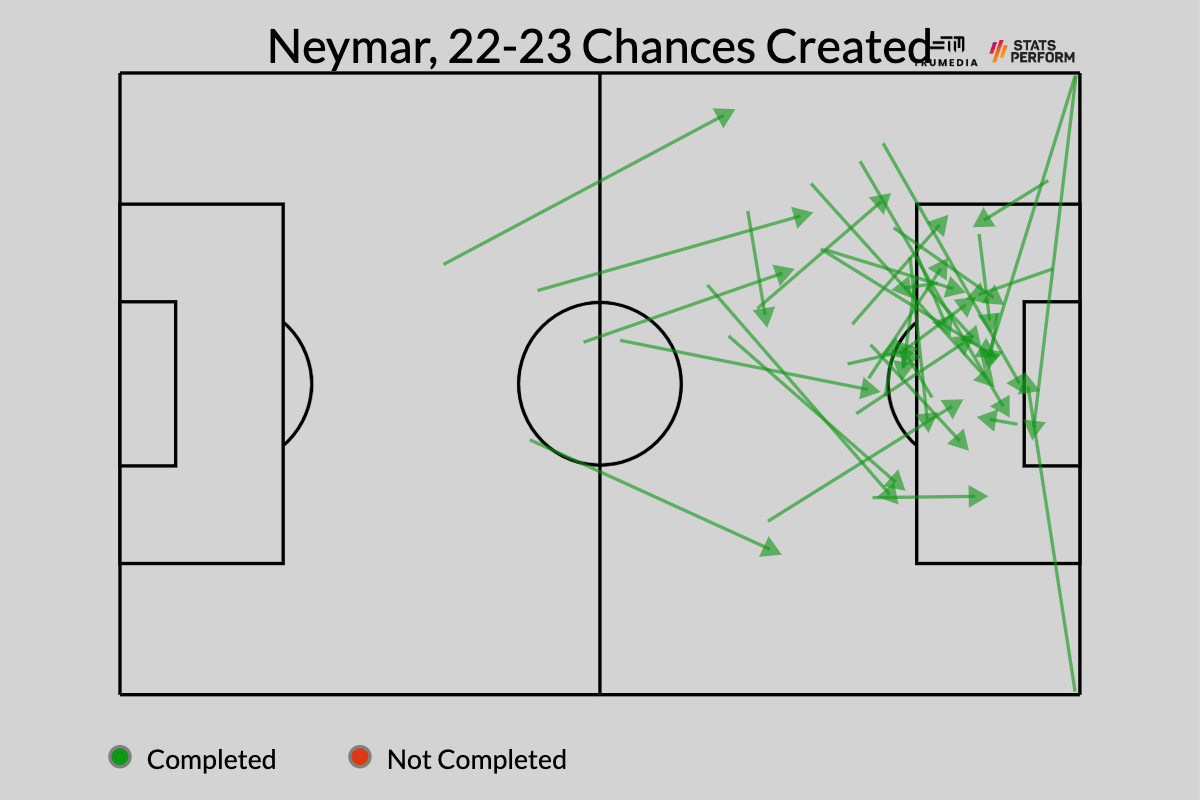

From expected goals, you can then take a step to expected goals assisted: Reward the passer with whatever the xG his pass created is. This strips out the quality of the shooter and instead rewards the passer for the quality of his passes, rather than what happened after he passed the ball. Leading all players across Europe's Big Five leagues in expected goals assisted this season is Messi's teammate at Paris Saint-Germain, Brazil's Neymar:

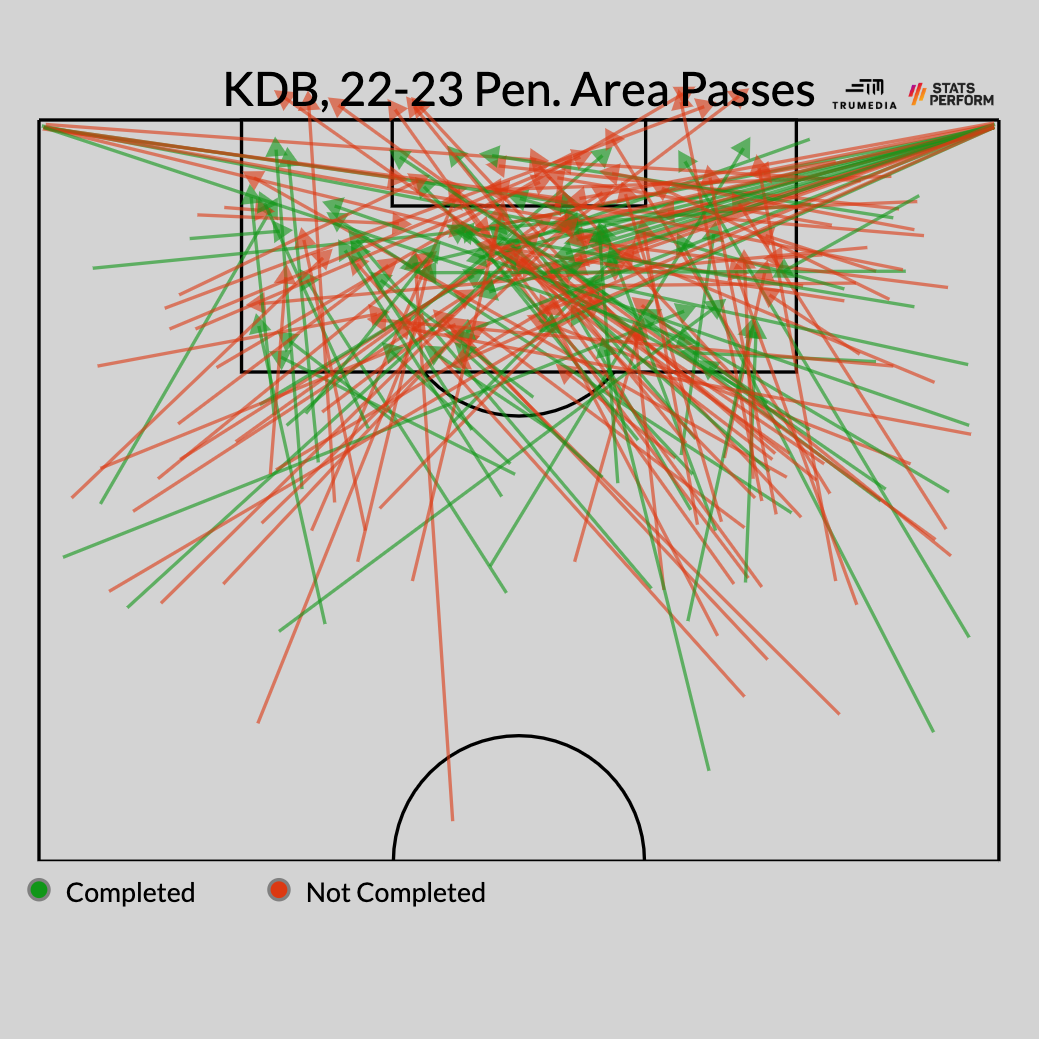

From there, you can take another step back and see who's playing the pass before the pass -- or, say, the pass into the penalty area. Messi, who's fourth in expected goals assisted, leads all players in Europe with 68. Next best is Manchester City and Belgium midfielder Kevin De Bruyne, with 50:

Take a step back from there, though, and things start to get really murky.

Luke Borrn, who was the head of analytics at Italian giants Roma before leaving to become the vice president of Strategy and Analytics with the Sacramento Kings, and is now a co-owner (along with Billy Beane) of French club Toulouse and Italian powers AC Milan, described the state of our objective knowledge of what's valuable on a field as such: "It's like the equivalent of if we only had data on dunks."

What happens in the midfield -- from a valuation standpoint -- mostly remains a mystery. When you look at actions that increase or decrease a team's likelihood of scoring a goal, everything that happens in the middle of the field pales in comparison to what happens near both goal mouths.

- Ranking every single World Cup: Which one is No.1?

Is this a calculation issue? Or does it require a re-imaging of the hierarchy of what happens on the field? It's probably a bit of both, but because of the patterns of play we're likely to see in Qatar, these players are going to have a much bigger influence on proceedings than they do in a given weekend across Europe.

Manchester City and England star Phil Foden takes on ESPN in a special shooting challenge ahead of the World Cup.

At the most recent European championships in the summer of 2021, passes were completed 84% of the time. In the Premier League season that followed, the number dropped down to 81%. On top of that, the ball moved toward the opposition goal at an average speed of 1.27 meters/second at the Euros, then leapt up to 1.39 meters/second in the Premier League. These seem like small differences, but with close to 1,000 passes occurring per game and around 200 total possessions per match, those differences really start to add up. There are fewer turnovers, and the game simply moves to a different rhythm.

With there being less pressure on the ball and with the ball moving upfield at a slower pace, the players in the middle have more time and space to make decisive plays. If you've only watched international soccer, you probably think that France's Paul Pogba is the best soccer player in the world.

If you've only watched club soccer, you probably think that Paul Pogba is one of the most inconsistent and hard-to-fit players in the world. That difference is due, in no small part, to the dysfunction of his former club Manchester United, but it's also due to the context in which he's performing. On the international stage, midfielders have more room and more opportunities to influence play near the opposition goal. With Pogba and his midfield partner N'Golo Kante out injured for France, that might spell trouble for what's been the heart of an uber-talented and successful team.

Germany lost Toni Kroos, one of the great midfielders of the 21st century, to retirement, while Spain opted not to select Thiago, who, when healthy, might just be the best midfielder in the world right now. Of course, a world-class midfielder is born every 15 seconds in Spain, so they're not wanting for depth. Croatia, meanwhile, made a run to the finals in 2018 behind a world-class midfield, and that group might be equally as good this time around. And if you're looking for a reason to be bullish about the USMNT, perhaps it's here: midfield is one of their strengths. With Tyler Adams (a destroyer and ball-winner), Yunus Musah (a vertical ball-carrier), and Weston McKennie (an off-ball runner and goalscorer), the pieces fit really nicely together.

Where does it all come together?

It used to be that coaches bemoaned set-piece practice: corners, free kicks, throw-ins, etc. Some, including Spain's Luis Enrique, still do.

Paul Power, now the director of Artificial Intelligence with the data company Skill Corner, used to work as a consultant with the Premier League club Everton. At the time, their manager was current Belgium manager, Roberto Martinez.

"There's this whole perception that scoring from set pieces is almost cheating," Power said. "You know, like it's not part of the beautiful game. Roberto Martinez just didn't practice set pieces. He wanted to know everything about open play: synchronization between players, how to create space through intricate movements. But if you looked at a set piece, there was no interest. This still kind of plagues soccer, from top to bottom."

In addition to the stigma around the set-piece goal -- as if it were an unfair or impure way to win games -- coaches would claim that any time spent practicing set pieces would take away from practice time elsewhere. In other words, if you started scoring more goals from set plays due to more practice, it would be canceled out by the decline in open-play goals caused by the decline in open-play practice time.

It's a sound-enough theory; it's also dead wrong, and proof of its invalidity came in the Danish first division.

FC Midtjylland, the most forward-thinking soccer club on the planet, scored 25 set-piece goals in the 2014-15 season en route to their first-ever first-division title. Eventually everyone else caught on and started to copy the champs. And a funny thing happened: Everyone else started scoring a ton of set piece goals, too, but their open-play goal-scoring remained unchanged. Despite spending more time on set-piece practice, their ability in open-play remained the same.

"It pointed to a huge under-exploited tactical wrinkle in the game that could help teams score enough goals to win a title," said Ted Knutson, who used to work for Midtjylland and now runs the data company Statsbomb. "And it's repeatable across the entire sport. That's a pretty big deal."

- Is Qatar's World Cup about "sportswashing" or something more?

Both Knutson and Power estimate that a good set-piece program can add somewhere around 15 goals in a given 38-game season. Why do they work so well? As the previous 2,000 words suggest, a lot of what happens on a soccer field is either random, difficult to quantify, impossible to comprehend, or all of the above. While you can't really pre-practice any specific open-play patterns, a set piece is the only time in the game the ball stops moving and a team can execute an exact plan: a chosen kicker, a pre-selected ball-flight, and then a collection of routes not unlike an NBA in-bounds play or any given NFL play.

According to research from Power, the average open-play possession leads to a goal 1.1% of the time while the mostly-still-poorly-performed set pieces lead to a goal 1.8% of the time. On corners, out-swingers lead to shots more often than in-swingers (20.9% vs. 18.6%), but in-swingers are more likely to lead to goals: 2.7%, compared to 2.2%. While much of the success comes down to the creativity of the play design, Power also pointed to the effectiveness of a ball flicked-on by a near-post header compared to one that's simply served into the "meat" of the box. Flick-ons are scored 4.9% of the time, while shots directly from the corner have a 2% success rate.

While there hasn't been a full-scale adoption of those ideas, the landscape is shifting, and quickly. Some groups, including Midtjylland and England manager Gareth Southgate, have even consulted with NBA and NFL teams on how best to create space in these situations. At the 2018 World Cup, there were 70 set-piece goals -- 43% of all the goals scored at the tournament. England themselves scored nine, breaking the record set by Portugal in 1966.

In Qatar, don't expect any drop-off in set-piece scoring. Hell, there might even be an increase. Given the limited training time afforded to national teams and the difficulty creating the kinds of cohesive creative structures that can conquer open-play, set-piece practice is even more time-effective at the international level. In 2018, the average team scored 1.3 goals per game. In a tournament that, at most, features seven total games for a given team, a couple extra set piece goals could be the difference between an early exit and a run all the way to the end.

There's bound to be plenty of uncertainty over the next month, but I feel pretty confident in making at least one prediction: At least one important game is going to be decided in the moments after the ref blows his whistle, when all that chaotic and dynamic movement briefly comes to a halt.