If you've been paying attention to the Premier League this season, you've already seen a lot.

You've seen Erling Haaland detonate what is supposed to be the best league in the world. You've seen Mikel Arteta prove the illogic of the managerial merry-go-round. You've seen Liverpool shoot themselves in the foot. You've seen Thomas Tuchel get fired less than two years removed from winning the Champions League. You've seen Manchester United make their first steps, in over a decade, toward establishing any kind of identity.

- Stream on ESPN+: LaLiga, Bundesliga, MLS, more (U.S.)

You've seen Leicester City nearly implode. You've seen AFC Bournemouth lose a game 9-0 and then go six matches undefeated. You've seen the end of the Bruno Lage Era. You've seen plenty of people calling for the end of the Jesse Marsch Era (despite a better-than-average expected-goal differential). You've seen the end of the "Steven Gerrard Will Succeed Jurgen Klopp" fairytale. You've even seen Nottingham Forest sign a small Caribbean nation's entire population worth of players, beat Liverpool and still end up in last place.

One of the few things you haven't seen: Crossing. While the once-widespread practice of getting the ball wide and whipping it into the box for an on-rushing target man has been on the decline for over a decade, the 2022-23 season might truly be the end of crossing as we knew it.

The death of crossing

Back in 2008-09, Manchester United and Chelsea were meeting in the Champions League final. Liverpool were leading the league in goal differential and still not winning it. And Arsenal, captained by a 21-year-old Cesc Fabregas, were passing the ball around at pace and comfortably finishing in fourth place.

This was the Era of the Big Four. Tottenham Hotspur were playing Gareth Bale as a full-back, grinding out an eighth-place finish from 45 goals scored and 45 conceded. Manchester City, meanwhile, were down in 10th, struggling to find consistency during the first year after the Abu Dhabi takeover. In fact, only one of the teams in the bottom half of the league in 2008-09 is still in the league today: Newcastle United, who were relegated with Alan Shearer -- yes, that Alan Shearer -- managing from the sideline. Also relegated, perhaps foreshadowing what just happened in the UEFA Nations League: Gareth Southgate's Middlesbrough.

The list of managers elsewhere in the league evokes a pure and very specific kind of nostalgia: Phil Brown, Tony Pulis, Martin O'Neill, Roy Hodgson, Gary Megson, Sam Allardyce, Mark Hughes, Steve Bruce, Tony Mowbray. You read off all those names, close your eyes and bask in the memories of that yellow Nike ball getting smashed into the penalty area from wide positions, over and over and over again.

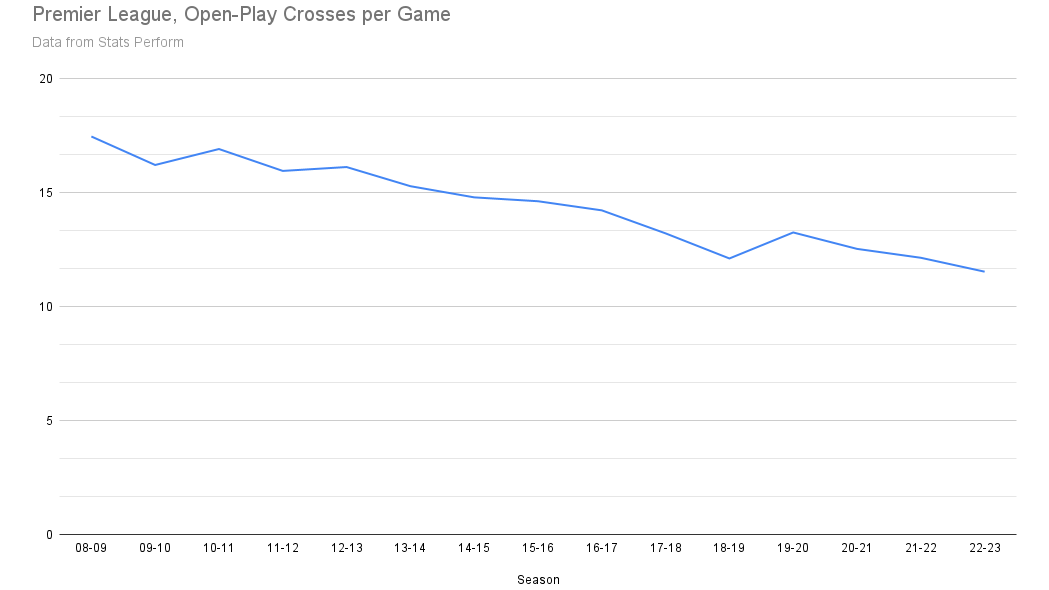

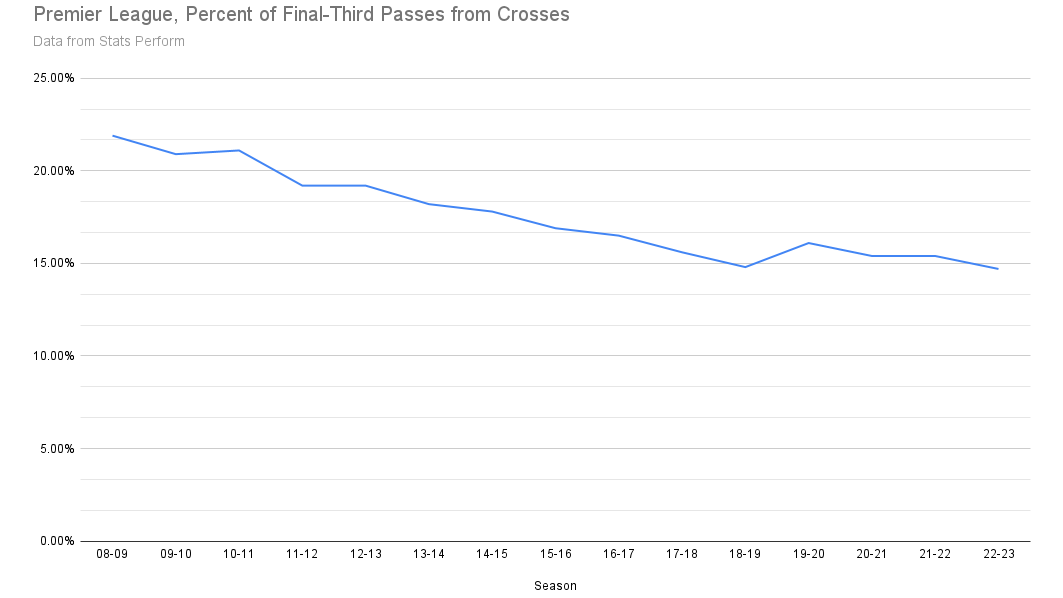

In the 2008-09 Premier League season, the earliest season for which Stats Perform provides, the average team was crossing the ball in open play 17.5 times per match. If you sat down on a given Saturday or Sunday, you were likely to see around 35 crosses attempted between both teams across a 90-minute game. In fact, 21.9% of all final-third passes were crosses back then. Saying that "every fifth pass in the final-third was a cross" would be to undersell how often balls were getting sent into the box.

Fast-forward to this season, and it's almost unrecognizable: Premier League teams are averaging 11.5 open-play crosses per match, and 14.7% of their final-third passes are crosses -- both of which are the lowest marks since 2008-09.

How James Milner explains the world

As you can see from this chart, it's been a pretty steady decline since the cross-heavy days of 2008-09. Save for a brief up-tick during the pandemic-interrupted season, when the way the game was being played did substantially change, the trend is clear:

Same goes when you look at the percentage of final-third passes that are crosses; in fact, the decline seems even steeper until the pandemic hit. The number dropped to 14.8% for the 2018-19 season before popping back up in the previous three seasons and then reaching a new low this year:

In 2008-09, Bolton Wanderers led the league with 33% of their final-third passes being crosses. This season, funnily enough, the leaders are West Ham United, who are managed by David Moyes, the only manager from the 2008-09 season still in the league today. However, West Ham, with 19.9% of their final-third passes being crosses, would've been only the 15th-most cross-happy team in the Premier League back then.

Back in 2008-09, Arsene Wenger's Arsenal were still England's supposed cultured continentals, prioritizing quick, short passing over what sometimes seemed like the easier and more direct route toward goal. However, compared with many of today's Premier League sides, they'd seem like they were dead-set on turning every match into a rock fight. In 2008-09, 16.6% of Arsenal's final-third passes were crosses -- more than 11 teams so far this season. The current iteration of the Gunners are crossing the ball with just 10% of their final-third passes, while Erik ten Hag's Manchester United are even more cross-shy, with a league-low 9.5%.

Among players with at least 500 minutes played, not a single player from this season would have ranked in the top 10 for open-play crosses per 90 minutes in 2008-09. Liverpool's Trent Alexander-Arnold's 5.74 per 90 would've ranked 11th, while only seven others would've ranked in the top 50. Three of them are Aston Villa players -- Leon Bailey, Lucas Digne and Matty Cash -- while Manchester City's Kevin De Bruyne, Tottenham's Ivan Perisic, West Ham's Vladimir Coufal and Wolverhampton Wanderers' Pedro Neto are the others.

Among players with at least half of their team's minutes played, the leader in 2008-09 was Aston Villa's James Milner with 6.65 crosses per 90. This season, Liverpool's James Milner is attempting just 3.34.

What's happening?

It feels like ages ago now, but back in December 2020, Arteta seemed to be clinging to whatever he could in order to justify his continued employment as Arsenal manager. After a 2-1 loss to Wolves, he went on the following rant:

"I think it is the first time in the Premier League that we put 33 crosses in," he said. "I am telling you that if we do that more consistently, we are going to score more goals. If we put the bodies we had in certain moments in the box, it is maths, pure maths, and it will happen."

Sarah Rudd didn't agree. The VP of Software and Analytics at Arsenal, when Arteta talked about maths and pure maths, pointed to crossing as one of the few easily exploitable inefficiencies in the modern game when I spoke to her for my book, Net Gains: Inside the Beautiful Game's Analytics Revolution.

"There are little things, like where [coaches are] teaching a full-back to come out and block the cross at all costs," she said. "And then you're kind of like, 'Let them cross from there. If they want to cross from there, that's fine.'"

Why would you let a player cross a ball from there? Well, in the same way you might let a basketball player take a shot from just inside the three-point line; it's inefficient. A 2014 study found that for Premier League and Bundesliga teams crossing had a strong negative relationship with goals; in other words, the more you crossed the ball, the less you scored. Other, more recent, work has found that crosses, on average, lead to goals somewhere between 1% and 3% of the time. Even when you look at goals that came after a cross but not directly from them, the goal-scoring percentage doesn't rise all that much.

The average shot from outside the penalty area, meanwhile, was converted 5.1% of the time in the Premier League last season, and that's not counting rebounds or other goals that came after the shot but not directly from it. So even if you're replacing the average cross with the average "bad shot," you're still significantly increasing your chances of scoring.

Arteta's current -- and Rudd's former -- club seem to have proven as much. In 2019-20, they averaged 14.2 open play crosses per 90 minutes and 14.9% of their final-third passes were crosses. The following year, those numbers dropped to 11.2% and 12.5%. And this season, they're down to 9.7% and 10%. Meanwhile, their points-per-game rates have gone in the opposite direction: from 1.6 to 1.8 to 2.5.

Of course, it's not that every cross is bad; you've seen De Bruyne or Alexander-Arnold kick a soccer ball. It's more that the game is moving away from the aimless, bad crosses from way wide against set defenses, focusing instead on cutbacks and low-crosses from near the byline, or early balls in behind a higher back-line. As the game has become increasingly globalized and domestic-league styles have fed off and influenced each other, most modern wingers are now playing on the "wrong" side, meaning they have to cut infield and away from traditional crossing areas.

In concert with this, teams are also relying less and less on the proper and/or traditional No. 9, a kind of immobile but aerially dominant big man who camps out inside the penalty area. So, there are fewer players who can actually cross the ball and there are fewer players whose main skill is getting on the end of crosses.

Perhaps, though, this has made crossing better. It's still early in the season, but 22.5% of open-play crosses this season have been completed -- a full two percentage points more than the previous high, from back in 2008-09. If everyone is relying less often on crosses in the final-third, then perhaps the only players still allowed to cross the ball without getting benched by their manager are the ones who are best at it. Maybe, without an obvious target to aim for, they're only crossing the ball when they see a clear passing lane and an open teammate. And maybe, one day, if the trend continues to head in the same direction toward less crossing, more intricate attacking play, and quicker, smaller defenders to stop it, we'll eventually see someone push for a return to 2009 ball in order to take advantage of all the players who no longer know how to defend crosses.

"Football is just really different from baseball [and other sports], in that you're constantly having these tactical innovations and revolutions driven by the coaching staff," Rudd said. "So a lot of those kinds of truths change really, really quickly."