Unless you're shirtless, on a beach, playing something called "dogfight football" days before a secret, low-probability mission to destroy a nuclear reactor in some unidentified foreign state, there is only one ball.

It's particularly a basketball truism -- one that gets trotted out every time a team assembles a new collection of superstar players. But like with so many overused sports clichés, it's factually true and it also scratches at a theoretical truth about how the sport works. At any given moment in an offensive possession, only one player can be touching the ball. The other four players, then, must find ways to help their team score without the ball.

There are two very different things. The player with the ball needs to be able to physically manipulate it -- in order to get a shot off, to move it into a more valuable area on the court or pass to a teammate in a better position. They also need to know where all of their teammates are, anticipate where they're going and understand when to get rid of the ball. The players without the ball need to move quickly and use their bodies to create space for their teammates. They also need to know when to stop moving and statically occupy the valuable area they're already standing in. But for that last one to matter, they also do need to offer a credible threat of scoring if they do get the ball, otherwise the defense can just ignore them.

The best basketball teams are the ones that navigate this balance of responsibilities with the least friction. And the best basketball teams I've ever seen are the two title-winning Golden State Warriors sides from 2017 and 2018. Their rosters were filled with capable off-ball players, but also had two of the league's best on-ball players in Kevin Durant and Stephen Curry. The overlap in their abilities could have led to diminishing returns -- whenever one of them had the ball, the other player wasn't able to do what he did best -- but that didn't occur because they both also happened to be two of the best off-ball players in the league, thanks to their abilities to move and shoot.

Another sport where there's only one ball is soccer. So, why can't we look at it -- how players impact winning, how they fit together -- in the same way?

The straw to stir the drink

Shaka Hislop feels Manchester City have no reason to worry that pressure will get to Erling Haaland in his first season in the Premier League.

What's your favorite YouTube highlight reel? I know the music is so-bad-that-it's-almost-good, and I know you have one. All soccer fans do -- because soccer games are boring. The ball moves around and nothing happens. Even when a player pulls off an incredible piece of skill or sees an invisible pass, it usually still ultimately ends in failure and a loss of possession. For watchers of soccer, highlight reels both completely rid the game of its overwhelming boredom and remove the disappointment that comes from a goal, inevitably, not being scored. You're just watching players do cool stuff, with no context, over and over and over again.

Of course, these reels are only vaguely connected to what makes an effective soccer player. My college roommate and I convinced each other that Mohamed Zidan was the second coming of Zinedine Zidane by watching his YouTube highlights. Who is Mohamed Zidan, you ask? Exactly my point.

The legendary player and manager Johan Cruyff did say: "There is only one ball, so you need to have it." But he also said: "When you play a match, it is statistically proven that players actually have the ball three minutes on average. ... So, the most important thing is: What do you do during those 87 minutes when you do not have the ball? That is what determines whether you're a good player or not." No part of those 87 minutes showed up on Zidan's highlight reels.

But enough about Zidan -- and more about how we think about soccer. If all basketball players are affecting the offensive end of the game by what they do on the ball and what they do off it, to varying proportions, then the same should be true of soccer even if no one individual player can touch the ball as often as one basketball player. I'm suggesting that it's a useful heuristic to think of all players as on-ball players, off-ball players or somewhere in between.

The analyst and writer Om Arvind has touched on this in a slightly different way, but the ultimate on-ball player is Lionel Messi. Even at his advanced age this past season with Paris Saint-Germain, Messi ranked in the 94th percentile or above at his position across the Big Five leagues in: shots, expected assists (xA), shot-creating actions, passes, progressive passes, progressive carries and successful one-on-ones. He's done all of that, for his entire career. It's why he's the greatest player ever.

The only two major attacking areas where he didn't do more of anything than everyone else were touches in the penalty area (64th percentile) and progressive passes received (24th percentile). These are both numbers that are overwhelmingly affected by what a player does before they get the ball. Messi can still affect the game without the ball because he's Messi -- the opposition are always ambiently aware of him and what he might do when the ball comes back to his feet -- but research has shown that much of his off-ball impact comes from how he stands still in high-value spaces.

The obvious NBA comparison is LeBron James; sure, he can impact the game without the ball here and there but he's so much better than everyone else with the ball that your optimal strategy is to have him touch the ball as many times as humanly possible. As Seth Partnow, formerly the director of basketball research with the Milwaukee Bucks and now helping the soccer consultancy and data company Statsbomb expand into other sports, put it to me, LeBron and Messi are the "straw to stir the drink."

While having either player on your roster pretty much automatically guarantees that your team will challenge for trophies in a given year, they also require a certain kind of player around them. Both Messi and LeBron have famously not meshed as well as expected with players who were previously stars elsewhere, because those stars also needed to have the ball to have their biggest impact -- except they were worse than Messi and LeBron, so you really didn't want them to have the ball.

A bunch of less talented players who were more adept without the ball were often better fits with both players, as opposed to bigger-name stars. It's likely no coincidence that Barcelona were at their best either with off-ball players like Pedro and David Villa ahead of Messi, or Ivan Rakitic and Jordi Alba behind him -- as opposed to, say, Zlatan Ibrahimovic or Cesc Fabregas. Oh, and ask any Lakers fan how the Russell Westbrook experiment is going.

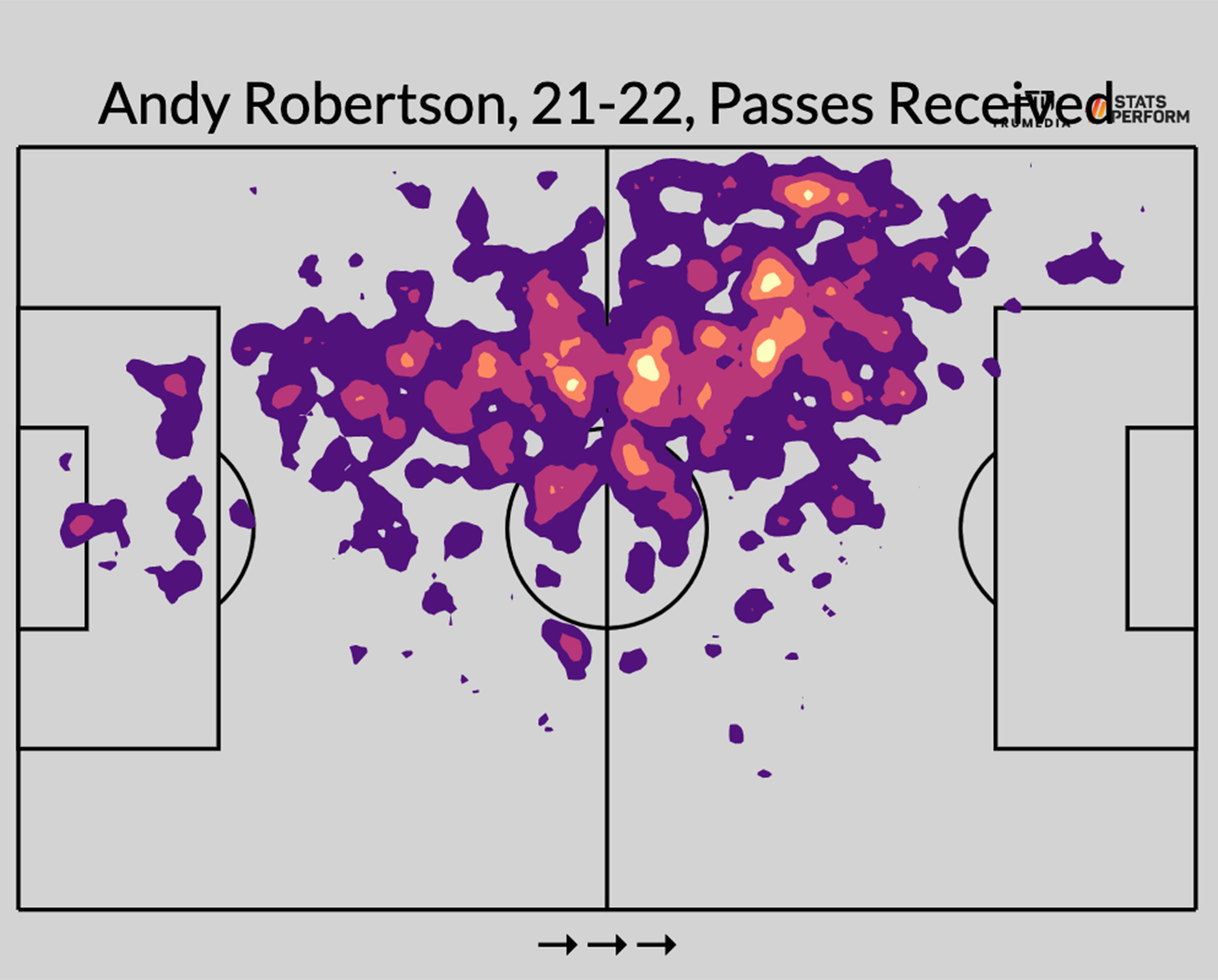

The balance applies all across the field, too. It's not really relevant for center-backs, but take Liverpool's full-backs. Trent Alexander-Arnold is the pure on-ball full-back; Liverpool have become an elite team as they've ensured that more and more of their possessions run through TAA's right foot. However, that's balanced out by Andy Robertson on the left side -- although not in a traditional way. The traditional form of balance would be a more defensive left-back, but instead Robertson stresses the space on the other side of the field from TAA, as he ranks in the 90th percentile or above at his position in both touches in the box and progressive passes received.

In the midfield, Liverpool's rivals, Manchester City, achieve a similar form of balance. Kevin De Bruyne is their TAA -- possessions run though him, his cannon of a right foot and his ability to drive the ball upfield. If they paired him with another passer in midfield, there would be that diminishing-returns issue mentioned above; if the other guy is making passes, then De Bruyne isn't on the ball, and so De Bruyne would be doing something he's worse at and the guy passing the ball would also be worse at passing the ball than De Bruyne.

Instead, Guardiola pairs De Bruyne with either Bernardo Silva or Ilkay Gundogan, two midfielders who complete an average-to-below-average number of progressive passes but who both rank in the 99th percentile at their possession for touches in the box and progressive passes received. They don't need a ton of touches to make an impact.

How Kane and Son make it work

You've probably seen the stat by now. It pretty much gets updated with each passing weekend at this point:

Son and Kane have combined for 41 Premier League goals

— PFF FC (@PFF_FC) July 26, 2022

They're already five clear of any other duo 🤯 pic.twitter.com/uOOJQF2XZf

Yet while it seems like Harry Kane and Son Heung-Min have been setting each other up for a decade now, no one was really talking about them as a dynamic duo back when Spurs were scratching at a league title under Mauricio Pochettino. A big reason is that they used to be similar players.

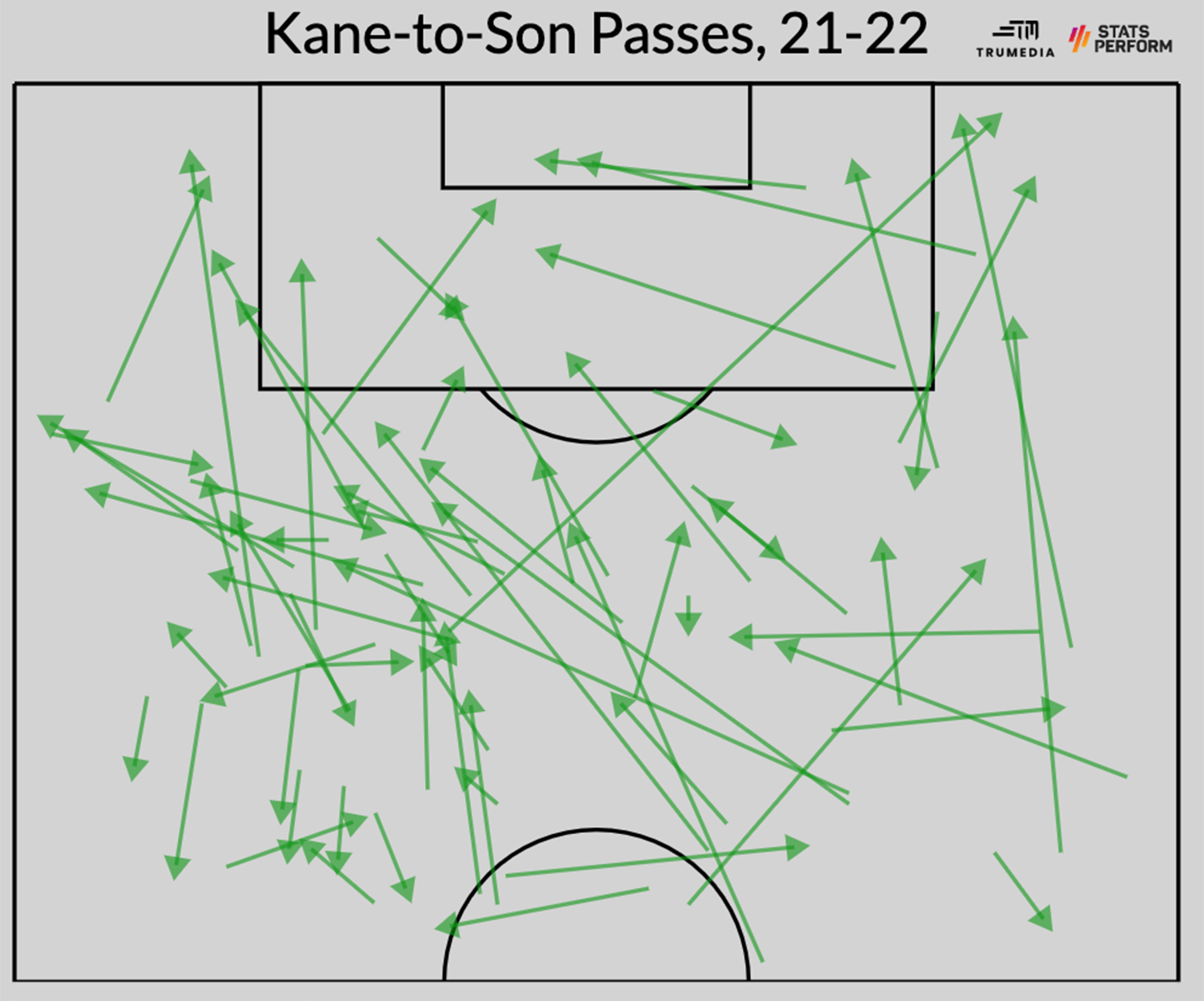

In 2017-18, Kane scored a career-high 28 non-penalty goals to go along with just two assists. He ranked above the 75th percentile in progressive passes received and touches in the penalty area. In other words, he found space in the final third, received passes in space and took a ton of shots (5.21 per 90, most in the league.)

Whether due to injury, roster deterioration around him or both, Kane has since steadily become more of an on-ball player. In 2017-18, Kane averaged 1.99 progressive passes per 90 minutes; this past season, he completed 3.26, 93rd percentile for all forwards. He registered 0.08 xA per 90 minutes in 2017-18, and this past season that number shot up to 0.25, 95th percentile for all forwards.

The shift in Kane's game has dovetailed perfectly with Son's strengths. He doesn't need to be on the ball too much; frankly, he shouldn't be on the ball too much. Whenever Son has possession of the ball somewhere deeper, it means he's not doing what he does best: running into space to score with either foot. Among wingers, Son ranks in the 48th percentile for passes completed and the 24th percentile for progressive passes completed. But he rates in the 81st percentile for progressive passes received -- and that distribution of responsibilities with Kane produced a much more important number this past season: 0.69 non-penalty goals per 90 minutes, or more than any other winger in Europe.

Further questions

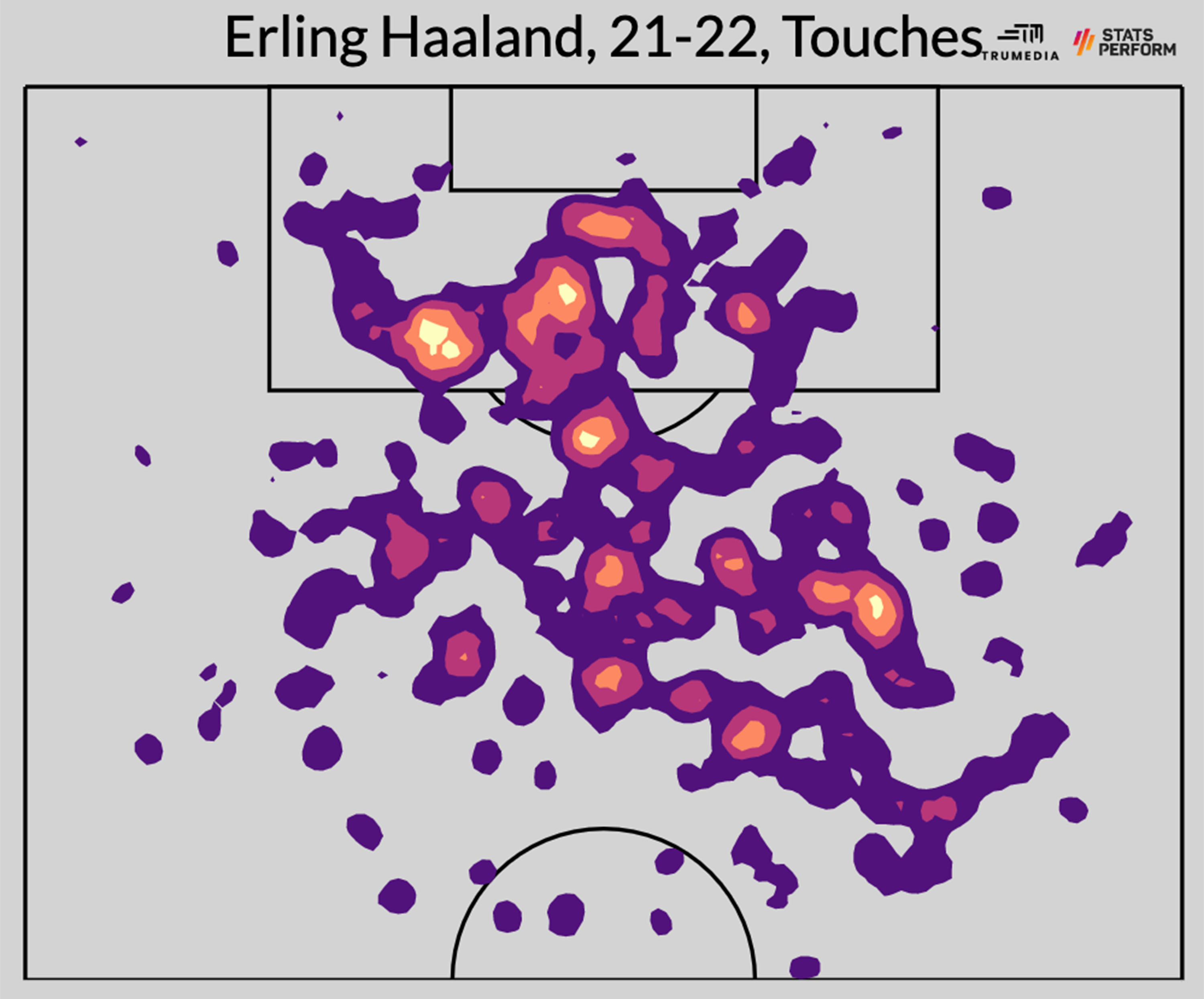

Last summer, Manchester City tried to sign Kane. It didn't happen, so they waited a year and ended up with Borussia Dortmund's Erling Haaland instead. The latter is seven years younger and theoretically will provide many more years of peak performance for the club, but that's not the pertinent difference between the two. No, it's how they play.

Kane's development into an on-ball creator (who could still score goals at a steady pace) turned him into what seemed like the prototypical Pep Guardiola striker. The manager, famously, wants his players to contribute to all phases of play. Except, Haaland, so far in his career, feels like the opposite of what Kane currently is. The Norway international completed just 22.39 passes per 90 minutes this season, which ranked in the 44th percentile among all forwards in Europe despite his presence on a ball-dominant Dortmund side. His progressive passing and carrying sat around a similar clip, too. His profile is actually a lot more similar to Son than it is to Kane: all pass receptions, off-ball runs and finishes inside the penalty area.

Perhaps, then, we should look at Haaland as a replacement for Raheem Sterling (and to a lesser extent Gabriel Jesus) rather than Kane. Sterling provides most of his value with all of what he does before he gets the ball, and that's why he's formed such a potent pairing with Kane. If City had signed Kane, maybe Sterling would have had more value to the way they'd be playing, while the more ball-dominant types they have in the same position -- Jack Grealish, Riyad Mahrez -- wouldn't fit as well. But Sterling and Haaland would have been looking to occupy the same areas despite not technically playing the same positions. So with Haaland and Phil Foden, another off-ball type, City now need their third attacker to, as Seth put it, be the straw to stir the drink. Grealish, in particular, is much better suited to that role than Sterling or Jesus ever would have been.

Elsewhere in Manchester, applying this framework creates a question about United's best player over the past few seasons: Bruno Fernandes. He's as much of an on-ball player as you'll find: in the 90th percentile or above for his position in total passes, progressive passes and xA. You don't watch Manchester United play and ever wonder where Bruno is; he's always doing something, always with the ball at his feet. But he's also only completing 75% of his passes, which is just a 47th-percentile mark for his position. Even with his inefficiency in possession, a team that let Bruno use so many possessions showed it could be a top-four team in England. But United want to be better than that, and it's unclear if they can be better than that with the attack running so heavily through Bruno, or if Bruno can be as effective as he is if he's not on the ball so often. In addition to the Cristiano Ronaldo complications, the pairing of Bruno and Jadon Sancho, another on-ball-leaning player, didn't have an additive effect on the team's performance.

"When a team overindexes on on-ball creation, it's weird because much like in soccer, it's an absolutely vital skill," Partnow said. "But it is also one that has diminishing returns. Whereas with off-ball stuff, you need the on-ball stuff to activate it. But once you have that, it's almost wholly additive."

The opposite problem might be one we see in November at the World Cup in Qatar. While the United States men's national team does have more high-level players in Europe than ever before, almost all of them have carved out their niches with their off-ball work. Chelsea's Christian Pulisic is a very similar archetype to Raheem Sterling, while Juventus' Weston McKennie is much more toward the Gundogan side of the midfield spectrum than the De Bruyne end. Timothy Weah, Brenden Aaronson and Antonee Robinson are all much more off-ball players, while the oft-injured duo of Gio Reyna and Sergino Dest probably fall somewhere in the middle, rather than toward the on-ball extreme.

So, if the USMNT fail to get out of their group at the World Cup, it might not be because of any of the popular concerns of the current moment: no striker, potential injuries or a lack of high-level club minutes for any of the theoretical starting goalkeepers. No, it might just be because the team doesn't have a straw to stir the drink.