Strikers don't matter. In fact, you might even be better off without them. That, at least, seemed to be one of the lessons behind Manchester City and Liverpool's recent domination of the Premier League.

Now there are plenty of differences between how the two best teams in England -- and perhaps the world -- came to dominate on the field. Liverpool never stop running; City reasserted themselves by running less. Liverpool turned their full-backs into attacking midfielders; City's entire team is attacking midfielders. Liverpool blow you off the field like the weather; City systematically pick you apart at an almost molecular level.

However, the one thing Pep Guardiola and Jurgen Klopp's teams shared was something they both didn't have: a center-forward. Man City scored 99 goals, and Liverpool notched 94 -- the sixth and ninth most in league history -- without a player occupying the role that historically provides the majority of those goals. Given how dominant both sides were, as arguably the two best Premier League teams of all time, it became really hard to argue that they overcame their lack of a certain classical player profile. Rather, it was more likely the opposite: Manchester City and Liverpool were so good because they didn't play with strikers.

Then the season ended and the two clubs almost immediately spent more than $140 million to sign a pair of large, powerful, central strikers in Borussia Dortmund's Erling Haaland and Benfica's Darwin Nunez. So what's going on? While both clubs were at the forefront of one tactical trend, they might already be preparing for the next one.

Steve Nicol and Ian Darke detail why Darwin Nunez would be the perfect signing for Liverpool.

The death of the center-forward

First, a brief history of modern soccer. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, there were central players, there were right-sided players and there were left-sided players. To take it a step further, you could divide the central players into left-center and right-center players. However you chopped up the guys in the middle, though, personnel was evenly distributed across the field in the three or four zones.

Within this tactical environment, games were frequently decided by who could control the middle. More specifically, who could control what coaches referred to as "Zone 14" or the rectangle of space sitting atop the penalty area. Studies found that the number of passes played into and from Zone 14 correlated highly with winning games. In 1998, France's Zinedine Zidane won the Ballon d'Or for his exploits on the edge of the box. A year later, Rivaldo, a Brazilian No. 10 who broke teams apart from Zone 14, won the same award.

The eventual reaction to this from a defensive perspective was to pack Zone 14 with an extra midfielder. In the years around 2005, managers like Rafa Benitez and Jose Mourinho sacrificed an attacker to make this happen, but it didn't matter. As opponents pushed more bodies forward in frustration, their teams could exploit all that newfound space in behind on the counterattack with just two or three of their attacking players.

- Liverpool confirm Nunez transfer

- The stats behind Nunez' remarkable season

- Transfer window watch: Mane, Nunez and more

The solution to this was provided, in different ways, by Guardiola and Klopp (and others too). Both managers have publicly emphasized the "half-spaces" -- the areas between the wing and the center of the field, a kind of zone of uncertainty between the opposition's central and wide defenders. We saw the era's defining names dominate from these areas: Both Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo scored more goals than anyone ever has despite starting their movements from wider positions. The best players in the world became wide attackers because it was so hard to consistently influence games in the crowded center of the attacking third.

Eventually, both Klopp and Guardiola phased out their central strikers completely, preferring more dynamic options who could aid in build-up play, attack the goal from unpredictable areas and tempt defenders out of Zone 14. The evolution all seemed to culminate this past season, with a strikerless City and a strikerless Liverpool dominating the Premier League to an absurd degree.

It's not just these two clubs, though.

This past season in the Premier League, a pair of players shared the Golden Boot: Liverpool's Mohamed Salah and Tottenham's Son Heung-min on 23 goals each. One thing they have in common: Neither one is a center-forward.

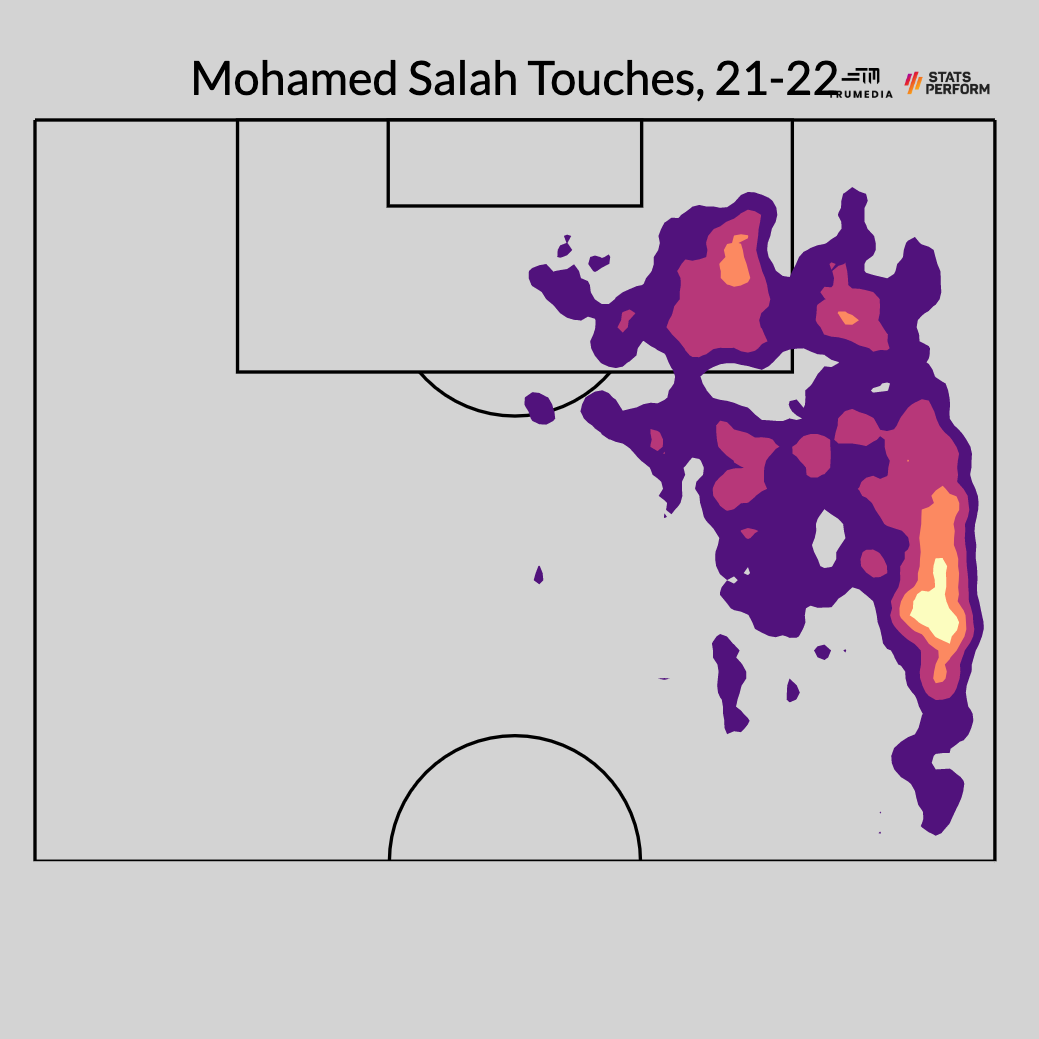

Here's where Salah took his touches in the Premier League:

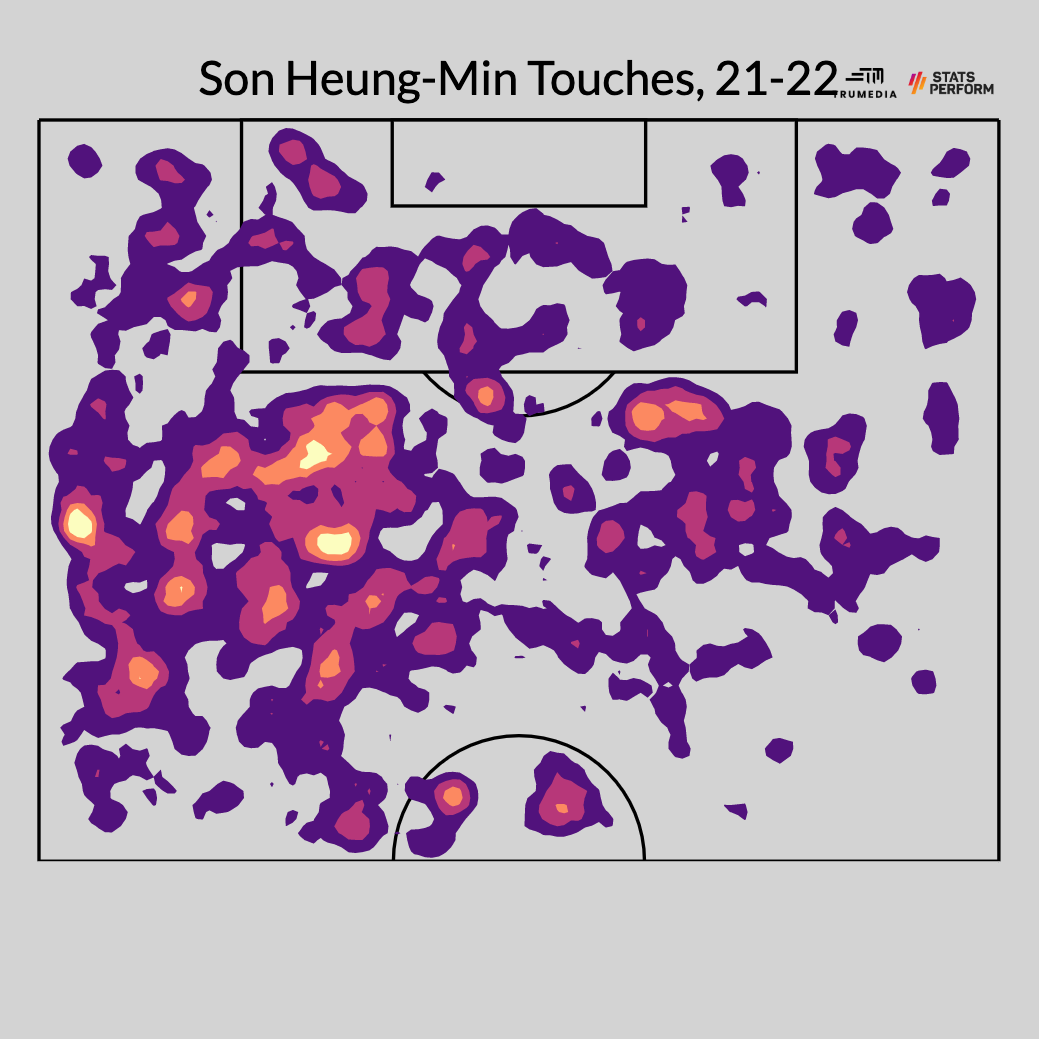

And the same for Son:

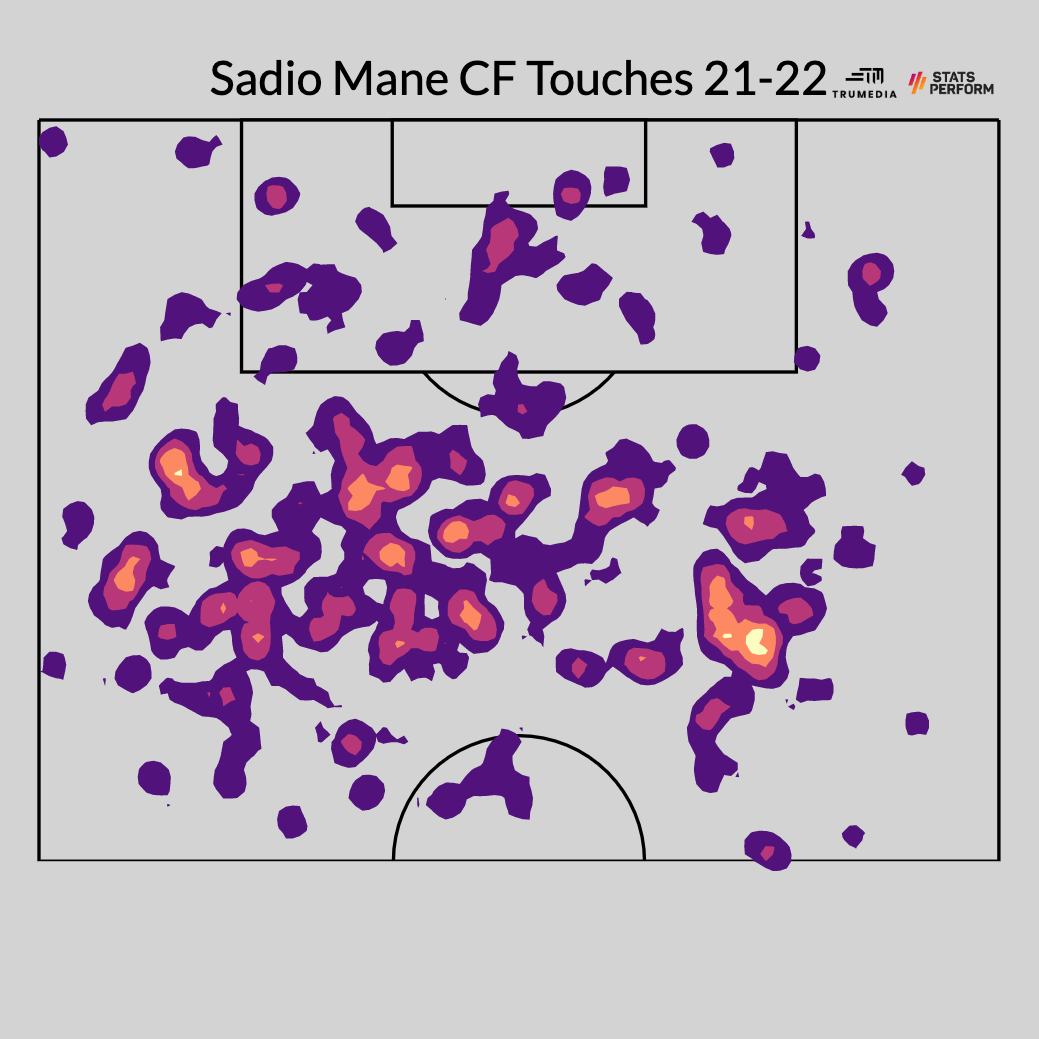

These are wingers who get tons of shots from inside the box by cutting onto their strong foot -- or strong feet, in Son's case. In terms of non-penalty goals, Son had 23, Salah had 18, then third in the league was Sadio Mane (16 goals), a left winger who turned into a "center-forward" during the second half of the season but really just wandered wherever he wanted to:

After that, four players were tied on 15: Man City's Kevin De Bruyne (a midfielder who moonlit as a false No. 9); Liverpool's Diogo Jota (a small, press-happy, flexible attacker who played across the front line); Leicester's Jamie Vardy; and Man United's Ronaldo. Fittingly, while the latter two are more traditional center-forwards, they are 35 and 37 years old, respectively, and while they both scored goals this year, neither helped his team come anywhere near achieving preseason expectations.

Then there's Tottenham's Harry Kane (13), a center-forward who has dropped increasingly deeper and impacted matches with his passing more and more over the past two seasons. On 12 goals, you have West Ham's Jarrod Bowen, a right winger, and Leicester's James Maddison, an attacking midfielder. And on 11, the only other player with more than 10 non-penalty goals in the Premier League this season was Man City's Raheem Sterling, another winger.

If you employed a traditional center-forward in the Premier League this season, one of two things happened: (1) He didn't score many goals or (2) your team wasn't very good.

And now for the rebirth

When there aren't as many center-forwards or those "center-forwards" aren't doing the things that a center-forward typically does, it affects the other side of the ball too. While the job of a center-back used to be about clearing crosses and "getting close" to the opposition center-forward -- denying service into their feet, not allowing them to turn -- now it's something quite different.

Functioning as a modern center-back is about tracking runs from different angles, cutting off passing lanes and covering space rather than a specific player. It's perhaps a less overtly physical position than it used to be -- less physical in an "I'm gonna beat you up" sense, but more physical in the increased agility and speed it demands from players. The days of the one-on-one matchup is over; now center-backs need to worry about the player in the middle, the players on both wings, the players making late runs into the box from the field and even sometimes one of the full-backs crashing in at far post or slipping into the half-spaces.

- Man City's summer isn't over with Haaland arrival

- Inside Story: How Man City signed Haaland from Dortmund

While modern players are more skilled and more well-rounded than ever before, the role of the center-back is perhaps the least recognizable of all positions as compared to what it was 15 or 20 years ago.

In addition to the high-speed calculus that's now involved when defending your own box, high-pressing teams require their center-backs to cover almost half a field's worth of space behind the backline. And thanks to a rise in those pressing teams, these players also have to be comfortable with the ball at their feet; otherwise, they'll constantly be turning the ball over and having to do it all over again. Oh, and if they're not being pressed, they have to help break the other team down by being involved in their side's more patient periods of buildup play.

Teams like Liverpool and City can afford to sign the handful of defenders in the world who can do all of these things, and they're the ones who've created the situation that now demands it. So why change?

Back in 2013, Sir Alex Ferguson spoke to the Harvard Business Review about how he maintained success for so long at Manchester United. "I believe that the cycle of a successful team lasts maybe four years and then some change is needed," he said. "So we tried to visualize the team three or four years ahead and make decisions accordingly."

Both Guardiola and Klopp have been at their clubs now for at least seven years, and their respective periods of success have lasted for about five years. Their teams are clearly the best in the league, if not the world.

"Because I was at United for such a long time, I could afford to plan ahead," Ferguson said. "I was very fortunate in that respect." Liverpool and City have created the same situation for themselves; neither one is really in danger of being caught by anyone else in the league, so they too can plan ahead.

While the transfer fees paid to sign Haaland (€60m, $62m) and Nunez (€75m, $78.5m) suggest they'll be expected to contribute immediately, they both seem positioned to have a bigger impact in the long run. The profile of the modern defender is shifting toward smaller, more agile and more skilled players, and it's likely to keep moving in that direction.

You know what kind of player these defenders increasingly won't be equipped to handle? Gigantic, physical, speedy center-forwards like Haaland and Nunez.

Weighted by minutes played, Liverpool (average age of 27.7 years) and City (27) have teams built around peak-age players. Haaland is 21, and Nunez is 22. There are questions about how both players will translate into the specific systems their new teams play. Yet, in year one, both Guardiola and Klopp have the luxury of easing their new center-forwards into action and employing them in matches that'll maximize their effectiveness.

For now, maybe Nunez helps Liverpool take more points against the top-four sides or the same teams that employ this modern archetype of central defender. And maybe Haaland's powerful runs into the penalty area help City play more effectively from behind. Or maybe they both star immediately because their opponents have already devoted so many resources to stopping the way that both clubs used to play. Either way, Liverpool and City now have players who, in theory, could lead the way toward a second cycle of dominance for both clubs.

First, you create the trend. Then you make sure you're the first one who figures out how to exploit it.