Back in a 1999 column, my old boss, Bill Simmons, coined the Ewing Theory. A friend of his "was convinced that Patrick Ewing's teams (both at Georgetown and with New York) inexplicably played better when Ewing was either injured or missing extended stretches because of foul trouble," he later wrote for ESPN.

Ewing was a star center for the New York Knicks, who drafted him No. 1 overall out of Georgetown in 1985. Unfortunately, his career directly coincided with a guy named Michael Jordan, so Ewing's Knicks won lots and lots of games, but never enough to secure an NBA title.

Ewing had just gone down with an Achilles injury during the 1999 Eastern Conference finals. The eighth-seeded Knicks were tied, 1-1, with the second-seeded Indiana Pacers. Everyone assumed the Packers would walk to the NBA finals, so Simmons wrote his column, debuted the Ewing Theory ... and the Knicks immediately won three straight games to clinch the series.

Over the 25-plus years since, the theory has been flattened and mocked. Oh right, so it's good not to have good players? Haven't the Knicks, uh, not been back to the Eastern Conference finals in the two decades since Ewing left the team? Of all the people you could've picked, you had to pick Patrick Ewing?

Simmons only landed on Ewing for the theory because a buddy of his was obsessed with that particular example, but the idea was more important than the individual. As he wrote in a 2013 update:

That's the thing about the Ewing Theory ... it takes various shapes and forms. Sometimes, we just overrated a player, or mistakenly believed he was more valuable than he was. Sometimes, an injury or departure can lead to more minutes for players who fit that team's style and framework better. And sometimes, it might take a simple injury for everyone to realize, We lost our way. We relied on that guy too much. I'm not doing enough. You're not doing enough. Let's step it up. You win a game or two, you build a little momentum, and before you know it, everything falls into place and you're a team.

Sounds familiar, right?

Like, what if the presumed best soccer player in the world, say, changed teams over the summer, but then his new team immediately got worse and his old team immediately got better? Or, you know, exactly what's happened with Kylian Mbappé after leaving Paris Saint-Germain for Real Madrid?

Let's dig into why Mbappé made Real Madrid worse, how PSG got better after he left, and what it all says about Mbappé as a player.

Why Real Madrid got worse with Mbappé

The downside case for Mbappé-to-Madrid was a pretty simple one: They brought in another attacker who doesn't defend, so while their attack might be lights out with Mbappé, Vinícius Júnior, Rodrygo, and Jude Bellingham, their defense is going to fall apart.

Last season, Madrid's defense was already getting by on individual brilliance -- great goalkeeping, the athletic range of their young midfielders and elite center-back play. The arrival of Mbappé, who is genuinely one of the worst and least active out-of-possession forwards in the world, was going to put even more stress on a defense that wasn't protected by a sound underlying structure.

Now, the defense has been worse this year, but not by all that much. These are their adjusted goals allowed (a blend of 70% expected goals and 30% goals) over the past two seasons, excluding penalties:

• 2023-24: 0.84 per 90 minutes

• 2024-25: 0.94 per 90 minutes

That's a decline, but based on the expectations for the attack with Mbappé added in, you would've taken three or four more goals allowed over the course of the season in exchange for the, I don't know, 10 goals you'd expect to add on the other end. And then when you consider that Éder Militão, David Alaba, Dani Carvajal, and Eduardo Camavinga have all missed significant amounts of time due to injury this year, it's not even clear that Mbappé's arrival has made the defense worse at all. Given all those injuries, we'd expect Madrid's defensive performance to decline a little bit.

That should've been a massive win for Madrid, but instead, the attack got worse. I can't stress this enough: The defending Champions League winners added arguably the best attacker in the world ... and then they got worse at attacking. Here are those same adjusted goal numbers for the other end of the field:

• 2023-24: 1.88 per 90

• 2024-24: 1.69 per 90

So, why didn't this work?

Truly elite attacks have three players who complement each other in new ways on every possession. Think Liverpool's front three of Mohamed Salah, Roberto Firmino, and Sadio Mané or Barcelona's current group of Robert Lewandowski, Lamine Yamal, and Raphinha.

These players all have multiple elite-level skills so, on one possession, we might see Raphinha drive the ball forward and slip a through ball to Yamal, who plays a cut back for Lewandowski to score the goal. On another, Yamal might draw four defenders, Lewandowski will dart across to the near post to take more defenders with him, and Raphinha will crash the far post to finish off a curled ball in from Yamal.

On the tier below that, you might have attacks where the players have more static skills -- each one is really good at one particular thing -- but it usually works because each of those skills complement each other.

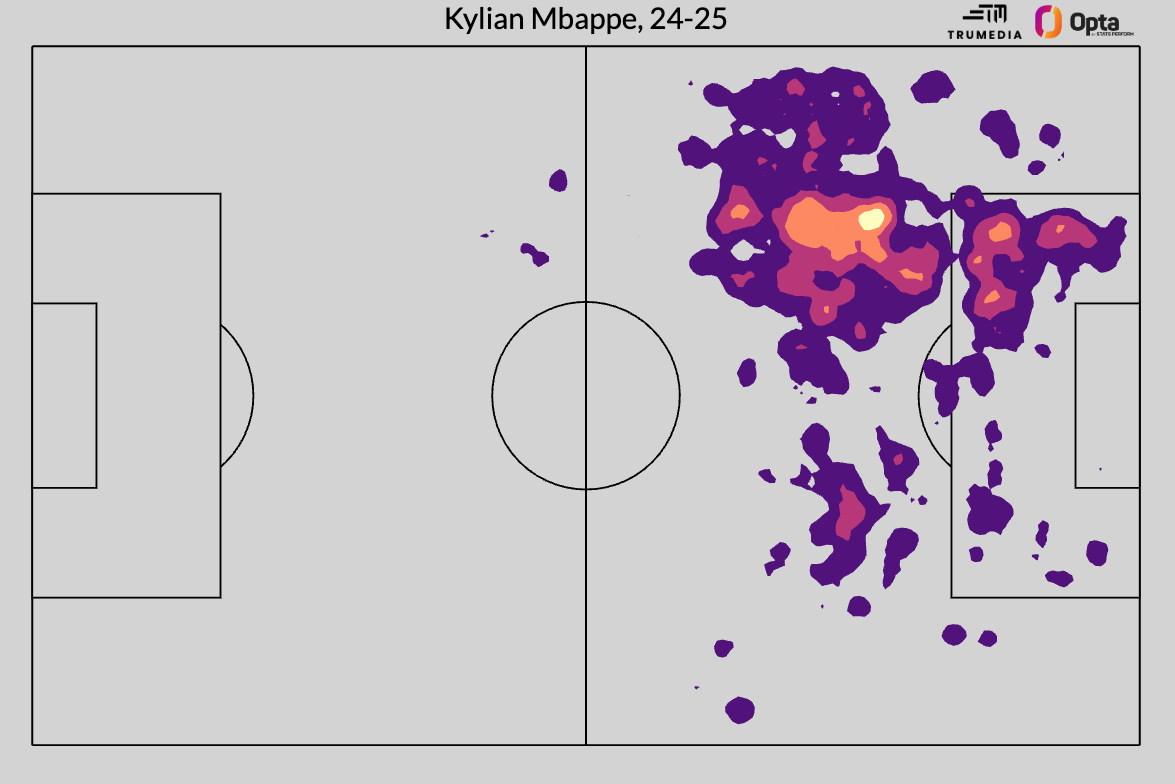

At Madrid, they've got none of this. Their two best attackers pretty much do the exact same thing: peel off to the left wing and try to run into the penalty area. Just take a look at Mbappé's heat map of touches for the season:

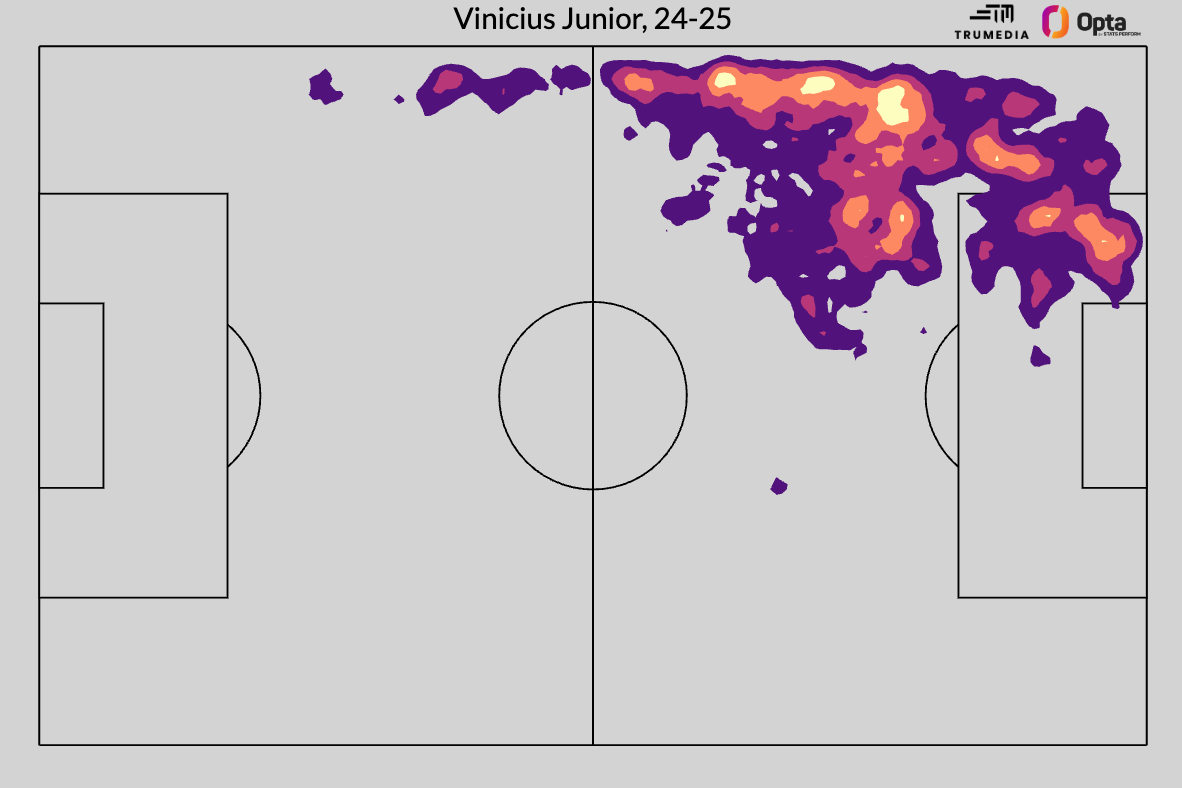

And then check out Vinicius Junior's:

Perhaps this could work if there was a third attacker who was constantly crashing into the center of the box, or maybe a ball-dominant creative type on the right who was springing Mbappé and Vinícius into these spaces on the left side.

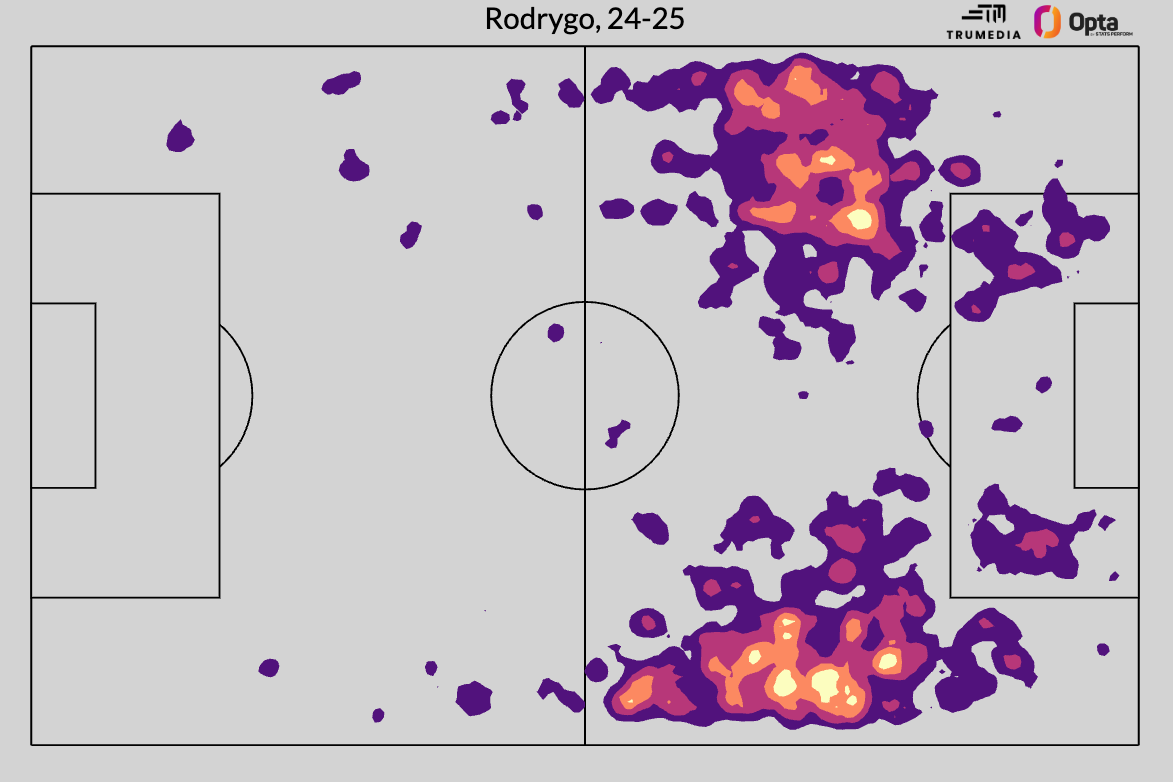

But among wingers in Europe's Big Five top leagues over the past 365 days, Rodrygo ranks in the 13th percentile for expected goals assisted. His heat map looks like this:

The common thread among Madrid's three attackers is that none of them are getting on the ball in the middle of the field. And here's a little industry secret about the middle of the field: it's where the goal is!

On top of all this, Madrid also lost midfielder Toni Kroos to retirement over the offseason, so the team never really had any kind of reliable, systematic way of getting the ball up to these forwards. Perhaps a more consistent pattern of ball progression would have brought the ball up to the forwards in a way where even their lopsided movements would've been able to rip apart unsettled or under-manned defenses.

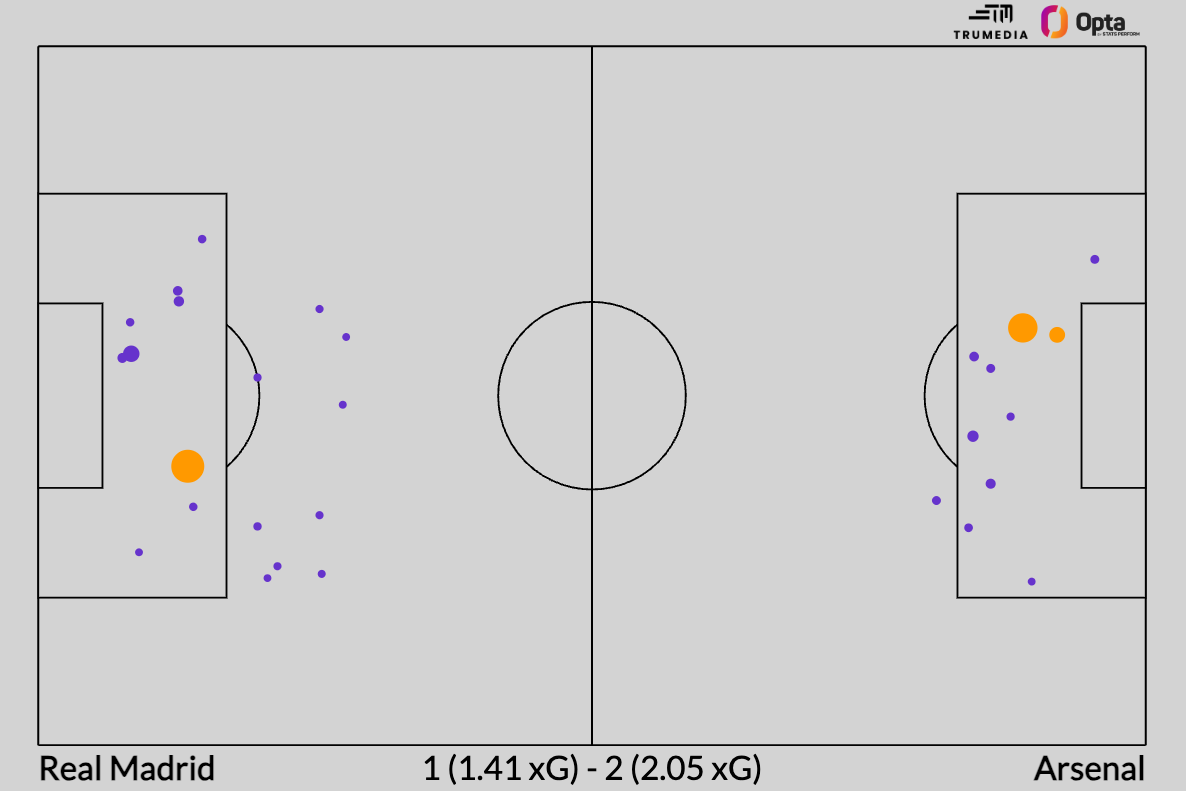

Instead, more often than not, it's looked like what we saw against Arsenal:

Needing to win by at least three goals at home, this collection of uber-expensive and super-talented attackers only created one decent chance off of a defensive error and otherwise were left shooting from tight angles and long distances -- far away from the center of the goal.

How PSG got better after Mbappé left

"The numbers speak for themselves. I still think we're better in attack and defense without Mbappé."

That's PSG manager Luis Enrique, right after his club knocked Liverpool out of the Champions League. And he's right.

By those same numbers we looked at for Madrid, here's how PSG have progressed defensively in Ligue 1:

• 2023-24: 1.02 adjusted goals allowed per 90

• 2024-2: 0.86 per 90

And for the attack:

• 2023-24: 1.94 adjusted goals per 90

• 2024-25: 2.56 per 90

Defensively, PSG are pressing more aggressively, winning the ball higher up the field, and allowing significantly fewer touches inside their own penalty area. On the other end, they're attempting almost four extra shots per game, playing more cutbacks, attempting more through balls, and getting into the opposition penalty area more often.

The only thing that's gotten "worse" is the quality of shots they're allowing: 0.09 xG per shot last season, now up to 0.10 this season. But even that, I think, is a good thing because it's indicative of a team that's able to press much more aggressively and much higher than last year. (With a high press, the best is that you'll allow better chances but also fewer chances, and it'll all add up to a decline in goals conceded.)

With Mbappé in the team, there's just no way PSG would've been able to press Liverpool off the field like they did this season. In the match in Paris, they held Liverpool to season-worsts in:

• Shots

• Expected goals

• Touches in the box

• Pass attempts

• Pass completion percentage

The attack also benefits from a press that keeps the ball in the attacking third for most of every match, and from the opportunities created by winning the ball back right as the opposition is transitioning from a defensive to an attacking structure.

Without Mbappé, who doesn't touch the ball a ton, is most effective in space, and likes to peel off left, the attack is also much more fluid and unpredictable. With the arrival of Khvicha Kvaratskhelia from Napoli in January, PSG now have four attackers who are devastating with the ball at their feet, but also comfortable running into space and slipping passes through the opposition backline.

The effectiveness of the press, too, allows both of their fullbacks, Nuno Mendes and Achraf Hakimi, to get forward aggressively and contribute to the attack.

While the various pieces of Madrid's lineup almost seem to actively negate each other, PSG's players all seem to amplify each other's strengths.

So what does this all say about Mbappé?

While I tend to believe that talent always trumps tactics -- and while almost every great manager is on the record in agreement with me -- that's the remaining elephant in the room.

When Bill Simmons outlined the Ewing Theory, he made it clear he wasn't saying that Patrick Ewing was necessarily worse than everyone thought. No, he was saying that specific circumstances sometimes create a situation where a team plays better without its best player, and the coaching circumstances at PSG and Real Madrid couldn't be any different.

Luis Enrique is one of the most tactically demanding managers in the world -- he has a clear way that he wants his teams to play, with and without the ball. And he's done a brilliant job at PSG so far this season.

It's not a given that a bunch of ball-dominant dribble-happy wingers should work so well in an attack, but Luis Enrique has figured it out, largely by freeing up Ousmane Dembélé to play centrally and do what he does best: everything, with either foot.

Meanwhile, Carlo Ancelotti said this at the beginning of last season: "I think the mistake new generation coaches make is that they give too much information about the system on the ball. I think old school coaches like me prefer not to give too much information and allow freedom for creativity."

That approach has worked brilliantly at Madrid, a club that's able to attract the best creative players in the world. But it has failed so far this season.

Without any clear plan on the ball, Vinicius and Mbappé's instincts always take them to the same area of the field. And sometimes, Rodrgyo joins them over there, too:

Now, Mbappé is still having a fantastic individual season. Michael Imburgio's DAVIES model, which values everything a player does on the ball, has Mbappé adding 10.57 goals compared to the average player at his position. That's the highest number of any player in Europe's Big Five leagues, and Liverpool's Salah (10.12) is the only other player with a number north of nine. More simply, he's leading Madrid in goals, expected goals, and expected assists.

But Madrid are simply a significantly worse team since he arrived. And the difference between Mbappé and everyone else on Madrid is that everyone else had already been a significant contributor to this team when it was the best team in the world, just one season ago. We've seen them do it -- we still haven't seen him do it.

For as productive as he is, Mbappé is just a really hard player to fit into an elite team. Since he refuses to press, he limits the approaches you can take without the ball. And while he's a winger, he's not the kind of high-touch player you can just ping the ball out to over and over again while he creates a ton of chances for himself and his teammates. You need a very specific blend of players both offensively and defensively to get the most out of Mbappé.

So, until further notice -- until we see Mbappé actually be the best player on the best team in the world -- we're officially designating Mbappé as soccer's face of the Ewing Theory.

In Simmons' 2001 column on the topic, he ended it by wondering, "Finally, what would be the greatest triumph for the Ewing Theory?" At the time, he suggested the 2001 Seattle Mariners winning their first-ever World Series after eventual Hall-of-Famers Randy Johnson, Ken Griffey Junior, and Alex Rodriguez all left the team. The Mariners won an MLB-record 116 games in 2001, but lost in the American League Championship Series to the New York Yankees.

Well, PSG lost Neymar and Lionel Messi two seasons ago. And now, with Mbappé also gone, they're undefeated in Ligue 1, and they're just three games away from winning their first-ever Champions League.