Is it a high bar or a low bar to clear? Either way, we're currently witnessing the worst season of Pep Guardiola's managerial career.

Since 2010, which is as far back as Stats Perform's dataset extends, Guardiola has managed 491 league matches across Barcelona, Bayern Munich and Manchester City, and his teams have won 1,177 points. That averages out to about 2.4 points per game; over a 38-game season, that adds up to about 91 points.

To put that into context: the team many consider to be the best in the history of the Premier League, Arsenal's Invincibles of 2003-04, won 90 points. In other words, the average Guardiola team was better than the only Premier League team that lasted an entire season without losing a game.

Of course, Pep's newest team has already lost five matches across all competitions. And through 12 league games this season, City have won 23 points, at an average of 1.92 points per game. If they keep it up for the remaining 26 matches, they'll win 73 points, well below the worst full-season tally of Guardiola's career: the 78 points a transitional, aging City squad won in his first season in England. Even with Bayern Munich in the Bundesliga, where they play only 34 matches, his teams never won fewer than 79 points.

The sky is falling ... and City are still in second place, a position almost any other club in England would be glad to occupy. Such is the floor when you combine the best manager of the modern era with a boundary-pushing ownership group funded by sovereign wealth.

But after winning four straight league titles, City are already eight points back of first-place Liverpool. And now they get to play Liverpool at Anfield, where Guardiola has won only once in nine tries. It's a chance to claw back points, but it's also their most difficult fixture of the season. Come the start of December, City could easily be 11 points off the pace.

How did we get here? Let us rank the reasons.

1. The defense has collapsed

It's not hard to describe the problem here. Since 2010, Guardiola's teams have conceded 0.7 non-penalty goals per game. This season, they're allowing 1.3 non-penalty goals. (Unless otherwise noted, we'll be referring to non-penalty goals as just "goals" for the rest of the piece.) Through 12 games, the defense has been nearly twice as bad as we've ever seen from a Pep side.

In the past, we've seen brief stretches where it seemed like Guardiola's teams couldn't defend, but that was usually because their opponents converted their chances at a higher-than-average rate. In Guardiola's first season with City, 2016-17, they conceded a goal per game despite only conceding 0.7 expected goals per game. They should've been a classic Guardiola defense, but then something went wrong in the brief moment after the ball left the attacker's foot.

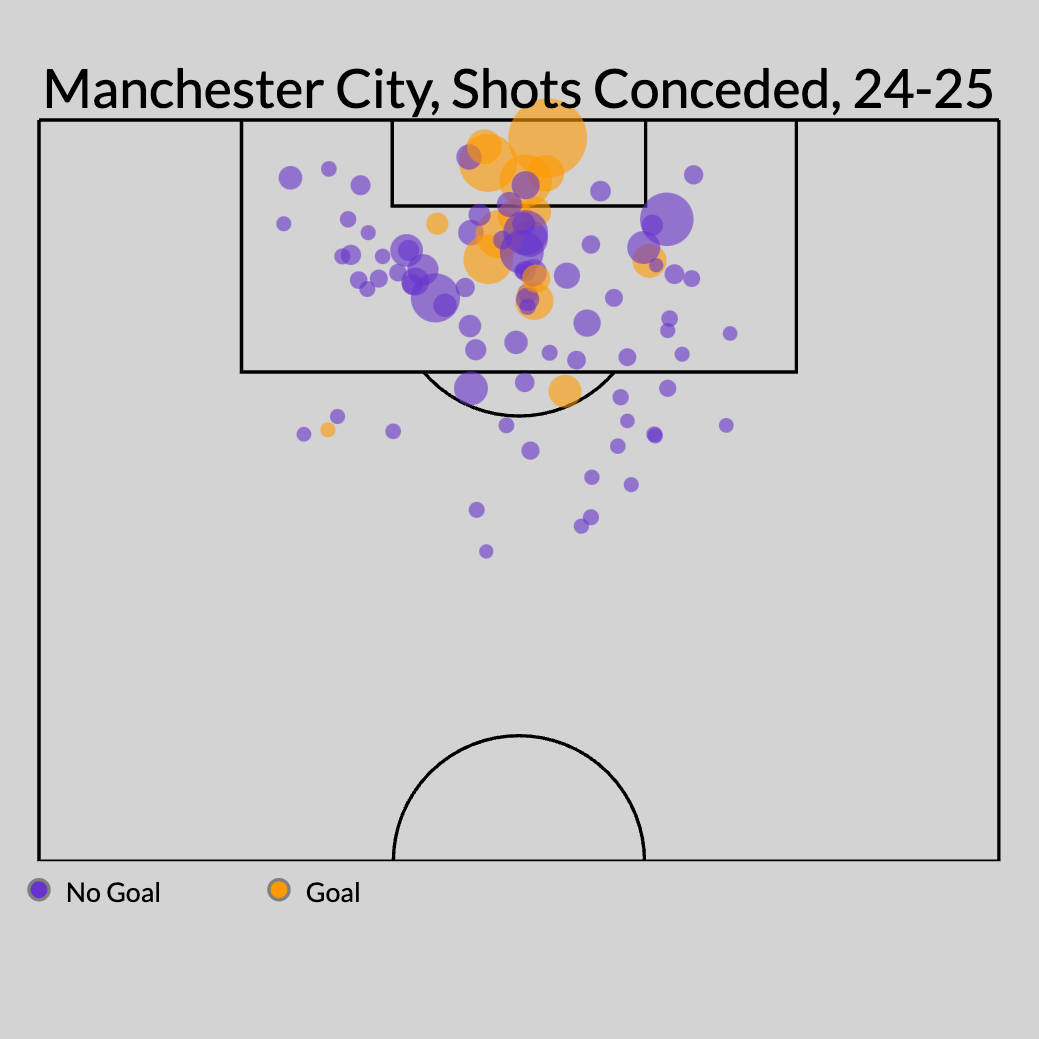

Ultimately, the problem that season was that Joe Hart and Claudio Bravo were both terrible shot-stoppers. That hasn't been the issue this time around. Éderson has actually conceded one goal fewer than expected based on the difficulty of the shots he has faced. Opponents are doing a little better with their shot placement so far this season, but that's just a marginal effect. The main issue is that City are conceding chances worth 1.2 expected goals per game.

There were already signs of issues last season. The 0.9 xG allowed per game was the joint worst in any Guardiola season since 2019-20, or the last time they didn't win the league. They also allowed 7.9 shots per game, the most of Guardiola's Manchester City era and the second most overall after his first season with Bayern Munich in 2013-14.

In 2024-25, City are allowing the same number of shots as last season; it's just that the shots are way more dangerous.

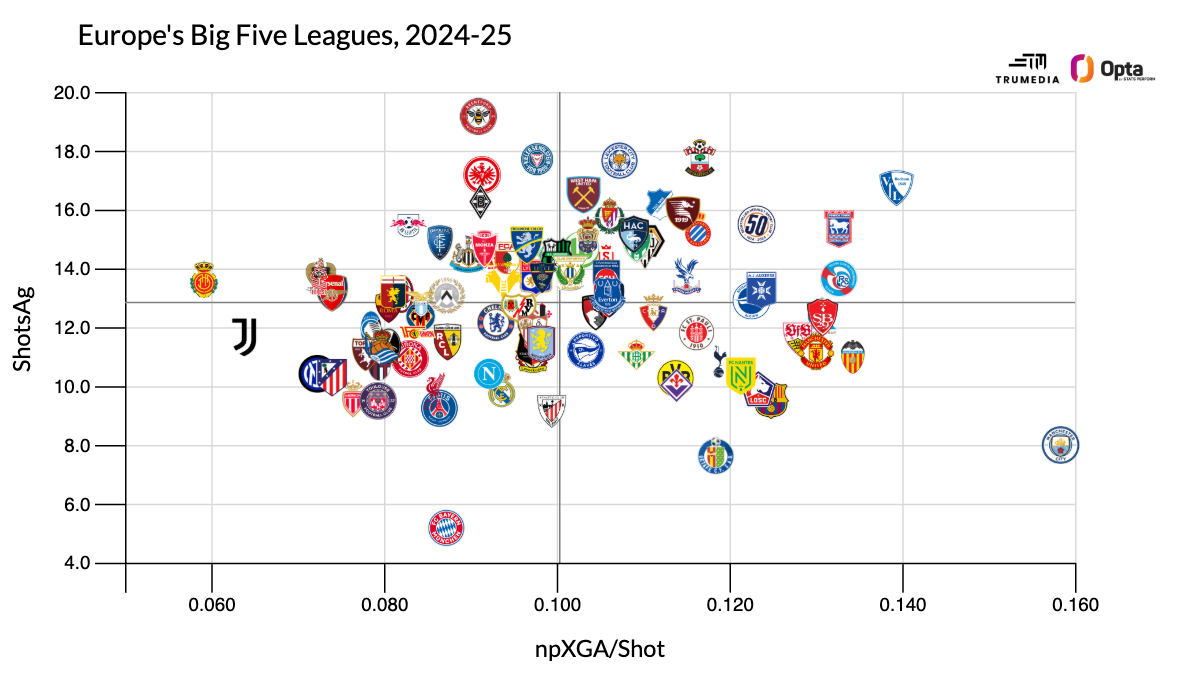

Since 2010, Pep's teams have allowed shots worth 0.10 xG on average, pretty much the average number across Europe's Big Five leagues. Their defensive dominance came from their ability to limit shots without allowing the quality to creep up. Well, this season, they're conceding shots worth 0.158 xG -- by far the highest number across Europe's Big Five leagues:

And somehow, I think that's underselling the issue. City's matches this season are averaging an absurdly low 69 possessions per team. The current trend at the highest level is toward fewer possessions, but Guardiola's teams have averaged 90 possessions per game since 2010. That means they're allowing more high-quality chances than ever before -- despite their opponents having fewer opportunities to attack them than ever before.

This team is broken.

2. Pep wanted a small team

Guardiola prefers a small squad. We know this because he has been happy to cut ties with any player who isn't fully committed to the City project. See: the fact that Leroy Sané, João Cancelo and Julián Álvarez no longer play for Manchester City.

We also know this because Guardiola himself has said it. "When you have 20 players and six injuries they say you should have bigger squad," he said last September, "but what happens when I don't have injuries? How can I manage that?"

Craig Burley says Pep Guardiola will be worried about Manchester City being swept aside by Liverpool in the Premier League this weekend.

That was Pep, reaping. This, three weeks ago, was Pep sowing: "We have 13 players so we are in real difficulty. ... When we are in trouble, like we are because in nine years it never happened, this situation, with many injuries for many reasons."

Despite comparatively unlimited spending power to build a bigger and more robust squad, Guardiola has preferred to keep things tight so he doesn't have to deal with unhappy players who aren't getting as many minutes as they think they deserve. We can't quantify the effects of this, but it's hard to argue with the results: City are the most dominant team in the history of English soccer.

However, it really feels like they finally flew too close to the sun.

City came into this season with arguably three irreplaceable players: Erling Haaland, Kevin De Bruyne and Rodri. De Bruyne was perhaps the easiest one to figure out -- the likes of Phil Foden, Bernardo Silva and Ilkay Gündogan can all do some version of what KDB does -- but he was also the most likely to get injured. He turned 33 over the summer, and he already missed half of last season due to injury.

Rodri, you know, uh, won the freaking Ballon d'Or. But he was also coming off an absurd season where he played nearly 4,000 minutes for City and then captained Spain's run to a title at Euro 2024. While City signed Mateo Kovacic and Matheus Nunes last summer, neither one is a Rodri backup. The former is an aging, elite ball progressor who can't cover much ground defensively and is also 4 inches shorter than Rodri. The latter hasn't really shown anything to suggest that he's good enough to play significant minutes for a team at this level -- and certainly not at the base of midfield.

Despite a history of injuries before arriving at City, Haaland had managed to stay mostly healthy across his first two City seasons. He only just turned 24, too. But he scored 49 non-penalty goals in the Premier League over the past two years, and someone would have to replace all of that if he ever did get hurt. Of course, the person who could've replaced him, Julian Alvarez, moved to Atletico Madrid over the summer. And then no one was brought in to replace him.

So, City came into the season with no backups to their two most important players. And their most creative player, De Bruyne, entered the season with significant injury concerns.

Haaland has been totally fine. He has started every league match, and his shots, expected goals and actual goals numbers are pretty much right where they've been over his first two seasons. But in a way, that means there's another path for City to get even worse; what happens if Haaland ever misses a significant amount of time?

We already know the answers when we apply that same question to De Bruyne and Rodri: City win a lot fewer games. Rodri is out for the season with a torn ACL suffered against Arsenal in late September, and De Bruyne hasn't started a match since he came off injured at halftime of Arsenal's scoreless draw against Inter Milan in mid-September.

During their recent five-game losing streak, City have been almost totally without both De Bruyne and Rodri. The latter obviously didn't play at all, while the former featured in just 41 minutes during that stretch.

Now, De Bruyne is genuinely one of the greatest midfielders in the history of the sport, and Rodri might be the best player in the world right now. Any team is going to struggle without those two guys at the same time, for a significant amount of time. But rather than preparing for that possibility, Guardiola & Co. have created a situation where it's bordering on Rodri and KDB or bust.

3. They've lost the balance

Two years ago, City entered their newest era under Guardiola. Despite winning the league over arguably the best Liverpool team of the Jurgen Klopp era in 2021-22 -- and doing so without a recognized striker -- the club added one of the least Guardiola-like players in the world the following summer.

Haaland's goal-scoring record before the age of 22 was basically unmatched in Europe, but that was it. He only scored goals. He rarely touched the ball, didn't aid in buildup play, wasn't playing through balls to wingers running behind, and didn't really defend all that much, either.

For a while, it seemed like Guardiola's ideal was a team of 11 midfielders. They'd never lose the ball and they'd be able to play through any amount of pressure. Haaland, though, wasn't this. And in response to the disruptive presence of such a one-dimensional player, Guardiola made a stark shift in City's defensive personnel.

Although he was one of the best full-backs in the world the season prior, Joao Cancelo suddenly fell out of favor by the midway point of the season. Instead, Pep almost totally abandoned the idea of the fullback and instead played what was close to four centre-backs across the back line. The left-back was typically a player who had been a centre-back for his entire career. And the right back, Kyle Walker, was basically a centre-back at this point in his career -- no longer able to cover an entire side of the field by himself.

What prevented the team from becoming fractured during City's quadruple-winning season -- defenders who mainly defend and a striker who only scores goals -- was the presence of Rodri, himself a centre-back at times in his career but also a destructive attacking force; the flexibility of John Stones, a centre-back who would slide into the midfield while in possession; and De Bruyne, the creative genius who could still pick a defense apart without as many bodies or as many dynamic movements to choose from.

Mark Ogden assesses the 16 first-team Man City players with contracts expiring between 2025 and 2027.

Stones rarely played last season, but his absence was made up for by Rodri putting together one of the greatest individual midfielder seasons of the modern era -- and also the addition of Josko Gvardiol, another centre-back moved to fullback, but who was much more comfortable on the ball and pushing forward than the players who occupied the same role in the 2022-23 season.

As such, City were pretty much exactly as good as they were the season prior. That's obviously no longer the case. Without Rodri, and KDB, and the marauding Stones, City have become what you might expect from a side with such stark player types: a team that can attack or keep possession or defend -- but not a team that can attack, keep possession and defend at the same time.

This number is somewhat skewed by the game they played a man up against Arsenal, but despite losing their two best midfielders for most of the season so far, City are controlling a higher share of final-third possession (76.5%) than any other Guardiola team since 2010. But part of the reason they've been able to achieve that is an incredibly conservative style of possession.

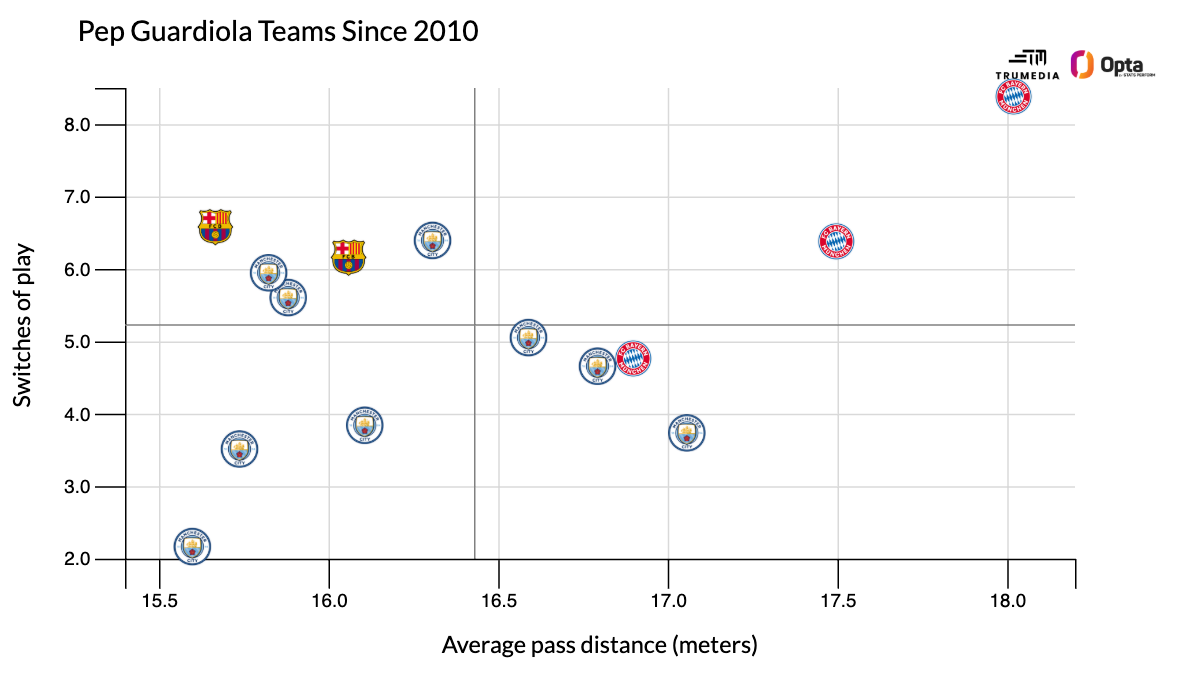

Guardiola often talks about how the key to soccer is to draw opponents to one side of the field with a succession of short, quick passes -- and then quickly move it to the other side of the field and attack the area the defenders have just vacated. City have been playing a ton of short passes this season, but they're totally lacking the other part of the equation.

Here's a plot of all the Pep teams since 2010, organized by their average pass distance and the number of times they switch the field per game. The current team is all the way in the bottom left corner:

In the upper left, you can see the 2010-11 Barcelona team that Sir Alex Ferguson said was the best side he'd ever managed against. They were the platonic ideal of the "tiki-taka" passing style, but they paired all of the short passes with a barrage of big switches that enabled them to attack into more advantageous situations. Pep himself has said "I loathe all that passing for the sake of it. ... You have to pass the ball with a clear intention, with the aim of making it into the opposition's goal." This season's team, though, has spent much of the campaign passing the ball without a clear intention.

Now, it's not like this year's City are a bad attacking team. They've scored 1.8 goals per game -- a mark that would be the worst for a Guardiola team since 2010. But they're still creating 2.0 xG per game -- exactly average for this era. There's no reason to think that their actual goals won't eventually catch up to the quality and quantity of chances they're creating.

The only problem: they're hoarding a wild amount of the ball. They're even getting into the opposition penalty area at will. Their 48.3 touches inside the box per game are seven more than the next-best number in Europe. But since they're moving the ball so slowly, they're arriving into the box with way more defenders in position and behind the ball than the average team faces.

And so, City are tilting the field massively, they're constantly breaching the opposition box ... and they're just an average attacking team for the Guardiola era and by far the worst defensive team he has ever coached.

4. The press no longer exists

Normally, there's a pretty high correlation between final-third possession and pressing. You keep the ball in the final third and prevent your opponent from reaching your defensive third by pinning them deep and then swarming the ball whenever you turn it over.

However, a press requires players who can defend and attack, players who are comfortable in various roles across the field, players whose natural inclination is to push high up the field. As City have moved away from these kinds of players, their pressing has declined.

If we discard the 2020-21 season when the coronavirus pandemic threw everything out of whack, the three least aggressive and effective pressing seasons of the Guardiola era are the three seasons since Haaland arrived. On average, Guardiola's teams have allowed 9.32 passes per defensive action (PPDA) and allowed an opposition pass-completion rate of 74.8%. Over the past three years, though, those numbers have ballooned upward:

2022-23: 11.63 PPDA, 79.5% pass completion allowed

2023-24: 12.34 PPDA, 81.8% pass completion allowed

2024-25: 11.13 PPDA, 84% pass completion allowed

Given that the PPDA is lower this season than in either of the past two -- despite City having to chase more games than normal -- Guardiola's side is trying to win the ball back more often, but it's also way less effective at it. Just rewatch the highlights from the 4-0 loss to Tottenham and see how easy it is to play through City and create a high-quality chance on goal:

The way City keep the ball in the final third is by all of that conservative possession in the final third -- not by pressing effectively.

Haaland isn't a great presser, and compared with Jack Grealish two seasons ago, neither are the new wingers, Savinho and Jérémy Doku, whom the club has signed over the past two summers. As more traditional, direct wingers, these players, too, are also more likely to lose the ball in disadvantageous situations that create easier opportunities for opponents to break. Rodri isn't out there to cover those spaces up anymore, and the rest of the roster has experienced its own physical decline.

Walker and Gundogan are 34. Stones, Kovacic and Bernardo Silva are 30. Manuel Akanji will be 30, too, by the end of the season. So, in a way, they have to play slower and more conservatively to prevent these transitional situations, but by playing slowly and conservatively, they're unable to create enough attack to make up for the defensive deficiencies.

And yet!

Despite all of that, I wouldn't put it past Guardiola to figure out some new way to make it all work. Part of me actually thinks that he's loving this, finally forced to use a limited set of resources to create an elite soccer team. But if he is going to solve this problem, it has to be something new.

All of the other Guardiola teams were as good as they were, in large part, because the players and the tactics complemented each other. The wingers balanced each other, the defensive midfielder allowed the fullbacks to push high, the centre-backs allowed the other midfielders to take more risks on the ball. The sum of their parts was better than almost every other team in the world, and then Guardiola got them to play at a level even greater than the sum of their parts.

This season, though, the opposite has been true. For the first time since Guardiola broke onto the scene with Barcelona in 2008, the tactical approach and the talents of the players seem to be making each other worse.