Last season, Manchester United finished in eighth place. Since the breakaway Premier League was formed in 1992, they hadn't ever been any lower. Over 38 games, they conceded one more goal than they scored -- also a club-worst in the Premier League era. In fact, the last time a Manchester United team produced a negative goal differential was back in 1990 when we still called it the "First Division."

For a team with higher revenues than all but four other teams in the world, United almost have to actively try to be this bad in order to be this bad again. And with a new minority owner, billionaire Jim Ratcliffe, taking over the club's football operations, plus Dan Ashworth (who helped rebuild England's national team, Brighton and Newcastle) leading the way in the new front office, perhaps a seventh, sixth, or even fifth-place finish seemed like it might be on the cards this season.

Well, nine games into this season, United are in 14th. They've conceded three more goals than they've scored, and they still haven't played against Manchester City, Arsenal or Chelsea. It's not quite United's worst-ever start -- they were minus-3 through nine games in Erik ten Hag's first season; in 2019, they had only 10 points during Ole Gunnar Solskjaer's first season.

In both of those other campaigns, United ended up finishing in the top four. Although we've seen them bounce back from situations like this before, we've never seen them be this bad, for this long. Now that they've sacked Ten Hag, let's run through five simple numbers that show how the club reached a new low under his leadership and why they had to make a change.

Points

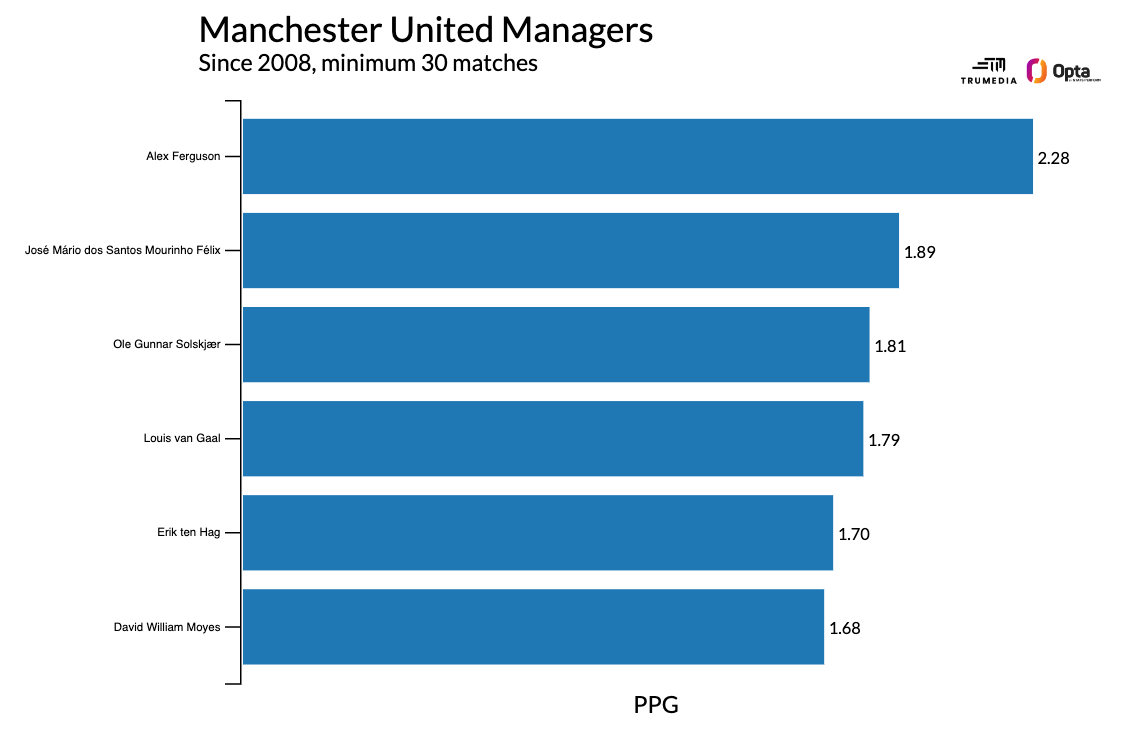

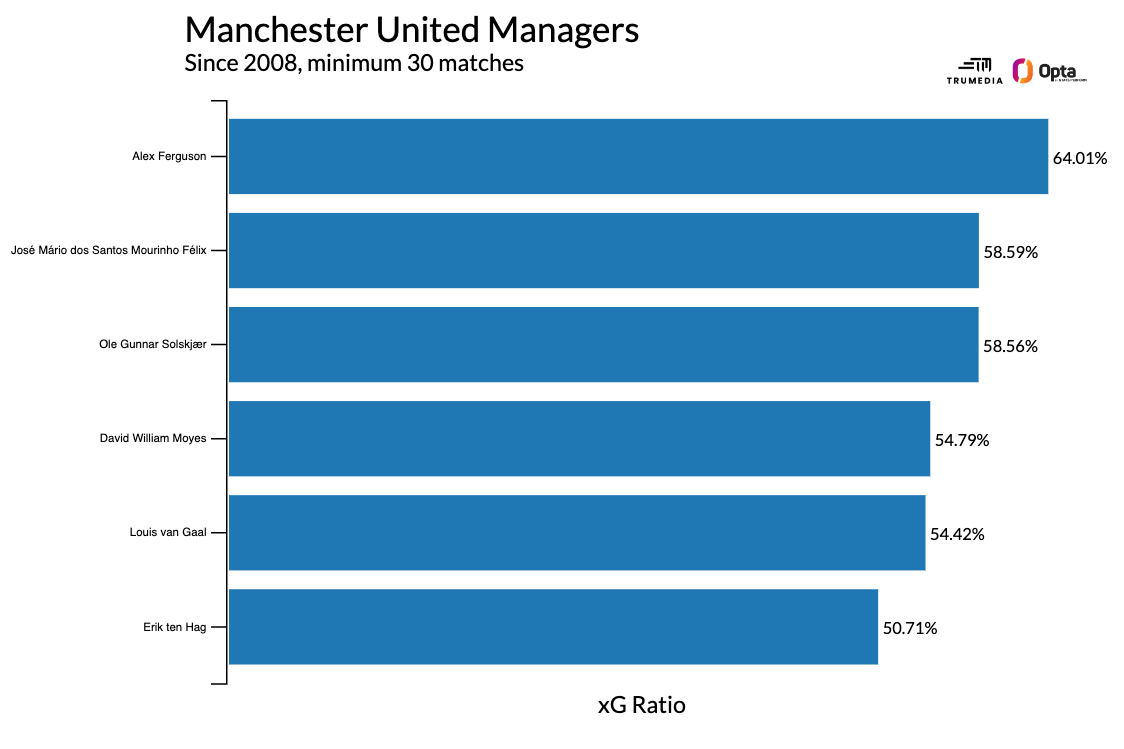

We'll start with the simplest one: points per game. The Stats Perform database goes back to the 2008-09 season for the Premier League. Since then, United have had six full-time managers. Here's how they stack up by points per game:

Over the course of a 38-game season, 1.7 points per game averages out to about 65 points.

In the 38-game era of the Premier League, Sir Alex Ferguson's teams never won fewer than 75; in Louis van Gaal's two years, 66 points was their worst; Jose Mourinho's two full seasons never went below 69; and Ole Gunnar Solskjaer's full-season minimum bottomed out at 66.

After Ferguson's unparalleled run of success, David Moyes took over and in his only season, the team averaged 1.7 points per game. He was fired after 34 matches. Ten Hag's teams won points at almost the exact same rate -- and he managed 84 Premier League games.

Goals allowed

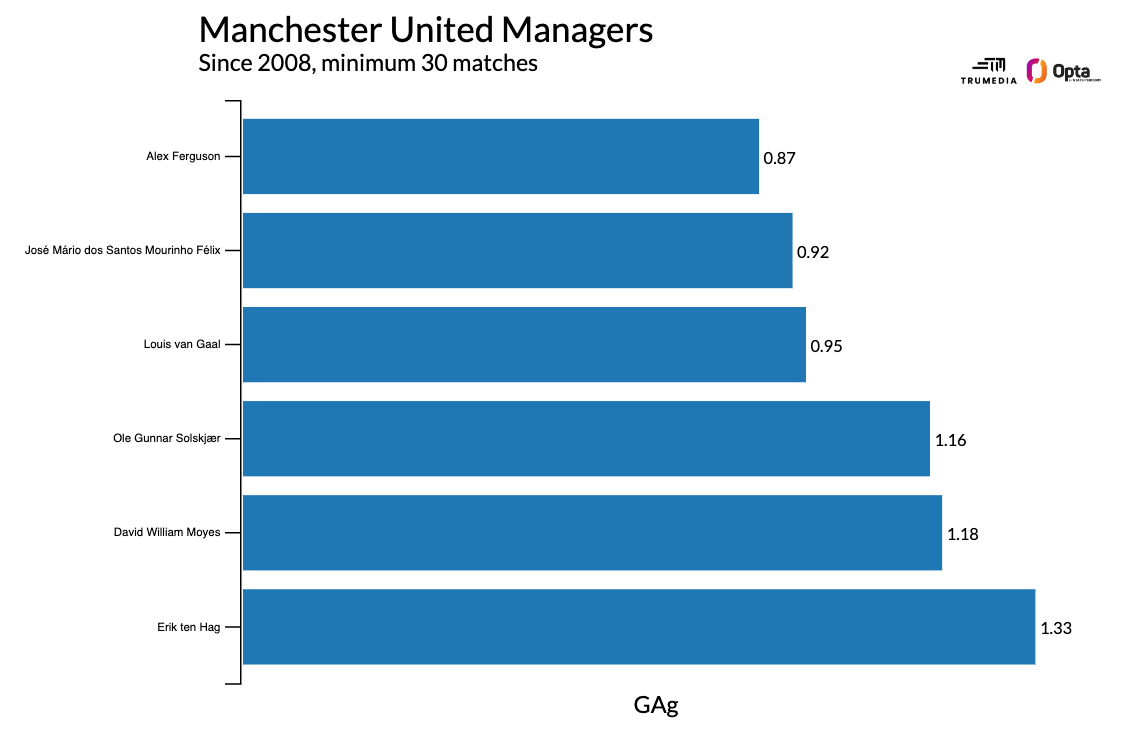

Broadly, the biggest problem of the Ten Hag era was that United seemingly let other teams score goals for fun. Here's how his defense stacked up to all of the managers before him:

Over the past five Premier League seasons, the average 10th-placed team has allowed 50.4 goals per season. Over Ten Hag's two-plus seasons in the Premier League, United have been slightly worse than that, at a 38-game rate of 50.5.

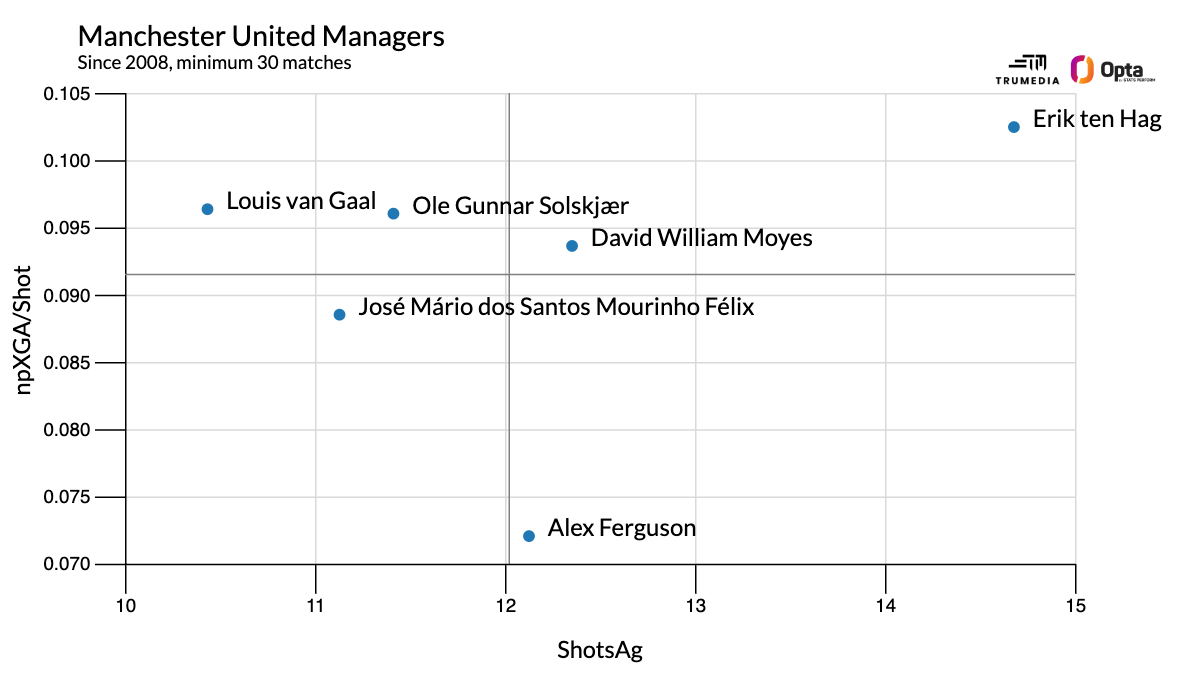

The story of why the defense was so poor is also a pretty simple one. Under Ten Hag, they allowed more shots and better shots than they did under any of the previous five full-time managers:

On top of that, they allowed 30 opponent touches in the penalty area per game. The worst mark, pre-Ten Hag, was the 21 touches conceded per game during the Solskjaer era.

Most managers are forced to make a trade-off with how they approach the defensive side of the game; concede fewer shots by defending aggressively, but allow higher-quality shots from the handful of times that aggression fails. Or allow a bunch of touches in the penalty area, but limit the quality of opportunities because of how many bodies you get behind the ball.

Under Ten Hag, United's defense had all of the downsides -- and none of the upsides.

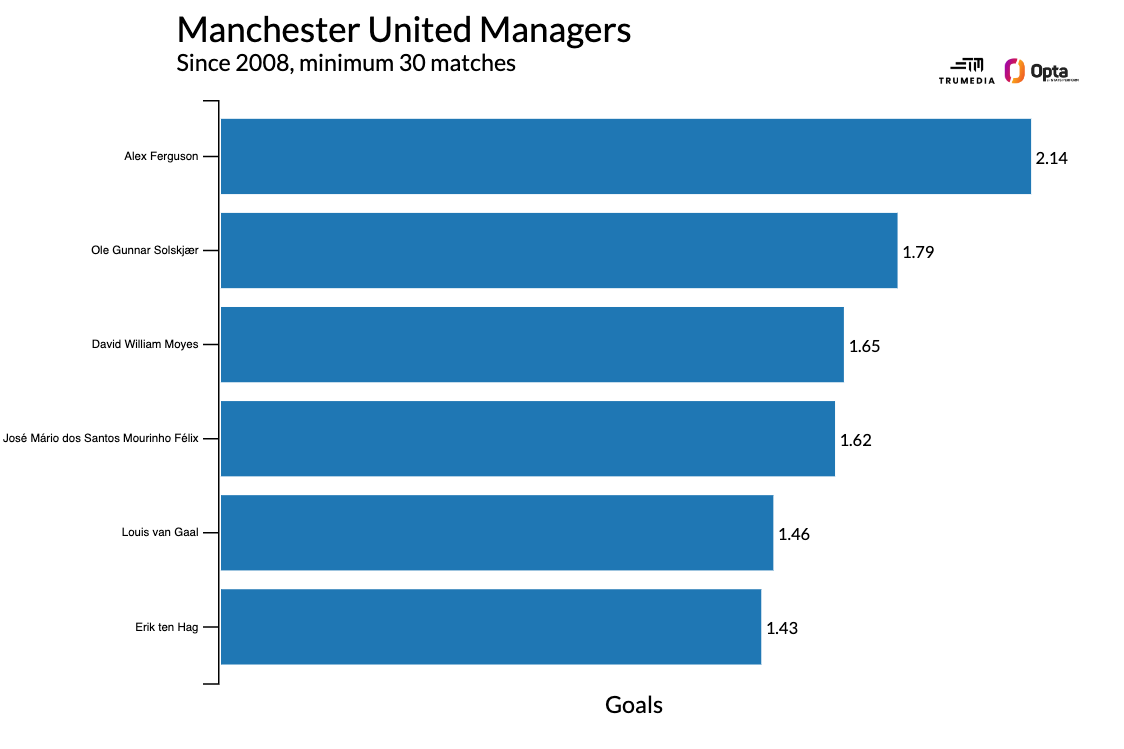

Goals scored

The other, larger trade-off is between defense and attack. Maybe you live with a creaky defense because you're pushing so many bodies forward and scoring so many goals. We're seeing it happen in real time, over at Barcelona. Under Hansi Flick, they press super high, they live on a razor-thin offside line, and do concede a fair amount of goals, but they score so many that it doesn't matter. They're probably the best team in the world right now because of the risks they take.

Except, with the steady defensive decline under Ten Hag, there was no real improvement at the other end:

In Ten Hag's first two seasons, United had been somewhat fortunate to finish as high as they did. Per expected points -- a metric that looks at the expected-goal difference for each individual game and awards an expected number of points to both teams -- United were sixth in 2022-23 and 15th last season. They, of course, finished third two seasons ago and eighth last season.

The one area, though, where Ten Hag experienced some bad luck is on the attacking end. HIs teams created 1.64 expected goals per game -- or just slightly below the joint-best 1.65 mark from both the late Ferguson era and the entirety of Solskjaer's reign.

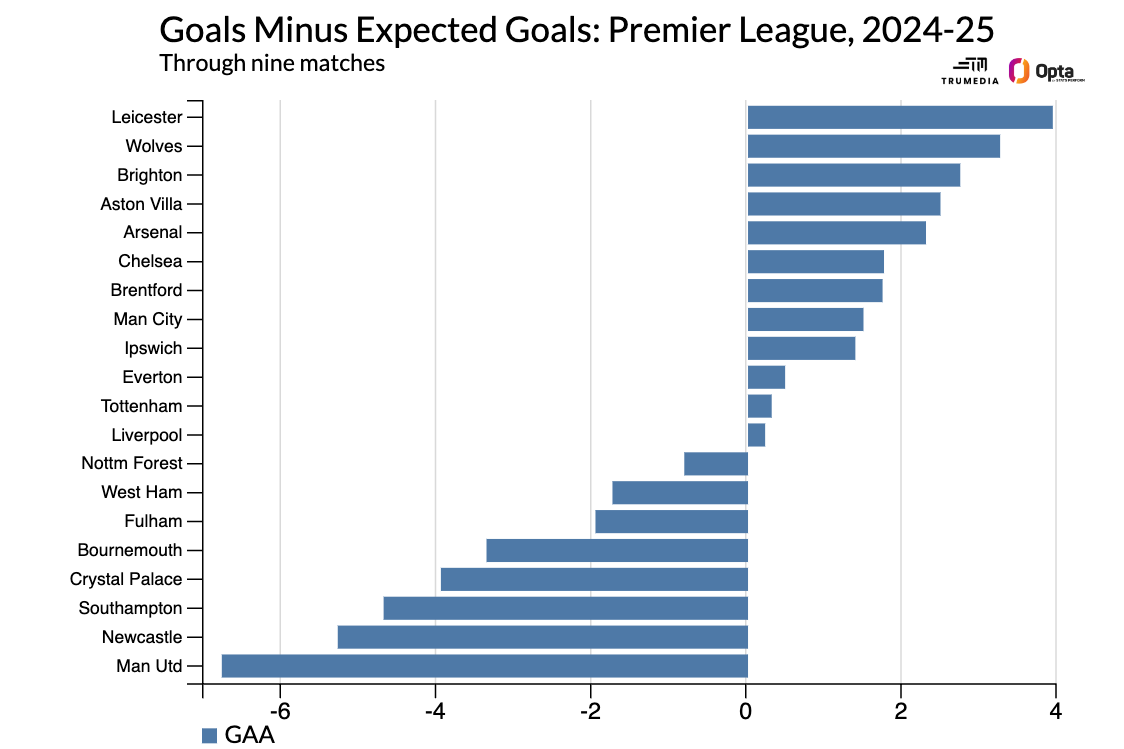

This season, in particular, United's finishing has been poor. The gap between their expected goals and their actual goals is the biggest in the Premier League through nine games:

But even accounting for that underperformance, United still have a negative expected-goal differential this season, and their expected-point total still only lands them in 10th.

It's the same story when you compare it to the five United managers before Ten Hag:

Ten Hag's United created just 50.7% of the expected goals from both sides in their matches. In other words, their average game was a coin-flip outcome for either side.

Pressing

Janusz Michallik can't believe VAR intervened to award West Ham a late penalty in their 2-1 win over Manchester United.

When United announced that they were hiring Ten Hag from Ajax, they referred to him as a manager "renowned for his team's attractive, attacking football." During his first preseason with the club, Ten Hag himself said: "We want to press, we want to press all day, and play proactive football."

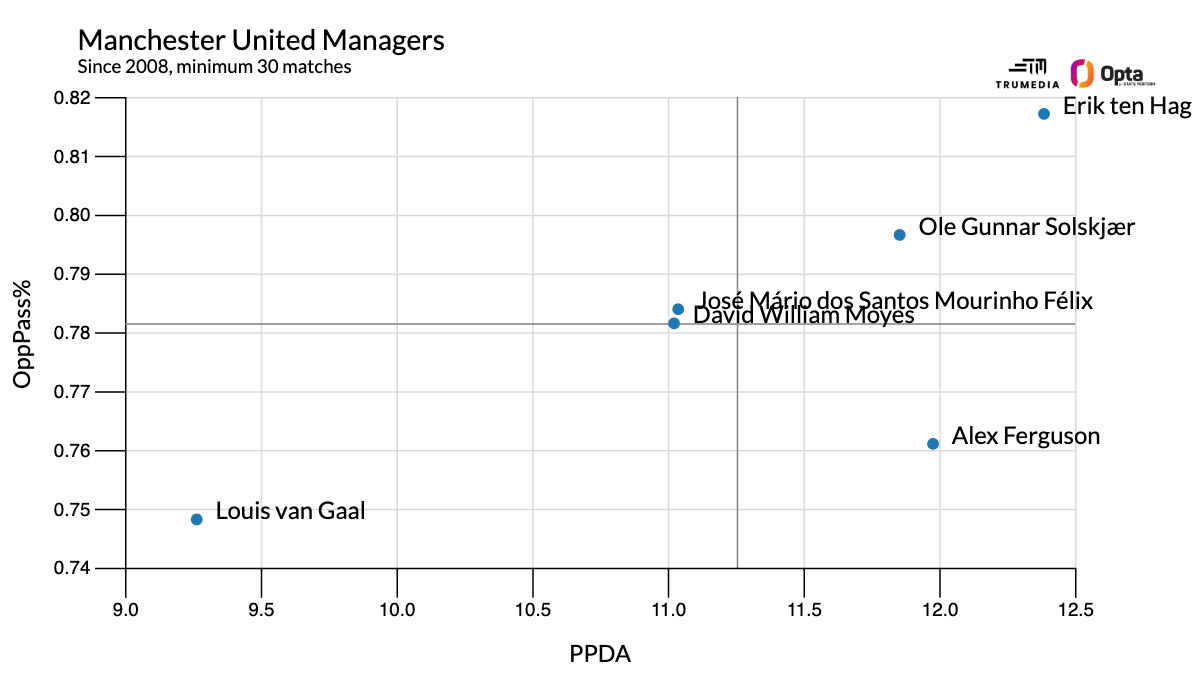

Two-plus seasons in, and that press never appeared.

We can quantify a team's intention to press by looking at their passes allowed per defensive action (PPDA), which is the number of passes a team allows outside of their defensive third before attempting a tackle, making an interception, committing a foul, or blocking a pass. Then, we can also look at the opposition pass-completion percentage allowed to see how effective the press actually is.

Under Ten Hag, United's PPDA and pass-completion allowed numbers were both higher than they've been under any of the previous five full-time managers:

Now, this isn't a perfect comparison because PPDA and pass-completion percentage have both been on the rise, leaguewide, over the sample of seasons we're looking at. But it's not inaccurate, either. Through nine games this season, United's PPDA ranks 15th in the league, and eight other teams are allowing a lower pass-completion percentage.

Possession

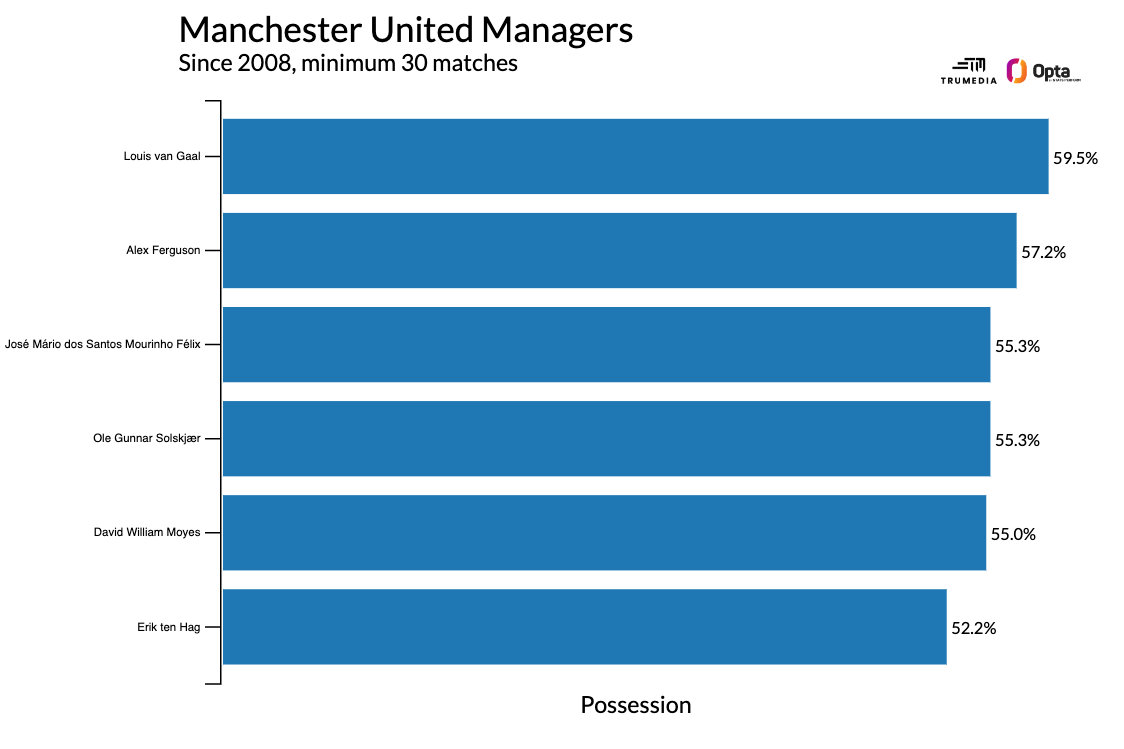

The core issue of the Ten Hag era was a simple one: They never found a way to control the ball. Every big club in the world has a plan for how to get the ball, how to keep it, and how to use those two things to create scenarios during a game when they generate more opportunities than their opponents.

While there are a handful of instances of clubs winning lots of points without much of the ball -- title-winning Leicester City, Atlético Madrid under Diego Simeone, Inter Milan under Antonio Conte, Monaco when they had all of the best prospects in the world for one year -- most modern teams create sustainable long-term success by keeping the ball away from their opponents. Ten Hag was certainly billed as the kind of coach who wanted to do exactly that.

Instead, United controlled a significantly lower share of possession under Ten Hag than under any of the five previous full-time United managers:

Usually, most successful managers have developed some cohesive sense of style with their team well before Year 3; some easy-to-identify things that they try to do, and some clear things that they do well. The likes of Jurgen Klopp (Liverpool), Pep Guardiola (Man City), and Mikel Arteta (Arsenal) all had their teams playing a certain way before they had them playing that certain way at an elite level.

Not only have the results not been there at United, but there's no evidence that they were on any kind of path toward anything. If there was any kind of strategic and stylistic idea that they were working toward, it was impossible to see it. They were absolutely hopeless without the ball, and never figured out a way to get it under Ten Hag.

Perhaps they'll have better luck under the new guy.