Despite a flood of new national television cash, 14 of the NBA's 30 teams lost money last season before collecting revenue-sharing payouts, and nine finished in the red even after accounting for those payments, according to confidential NBA financial records obtained by ESPN.com.

The gap between the league's most profitable teams and its weaker siblings will be addressed at the league's Board of Governors meeting on Sept. 27-28 in New York. Owners have planned a half-day review of the league's revenue-sharing system, sources said.

Some teams in smaller markets struggling to keep up with a fast-rising salary cap have pushed the league's richest franchises to share more of their profits, according to ownership sources. Some have argued that the expanding profitability gap could warp competitive balance: If big-market teams can earn fat profits even while paying the luxury tax, they could in theory hoard more stars.

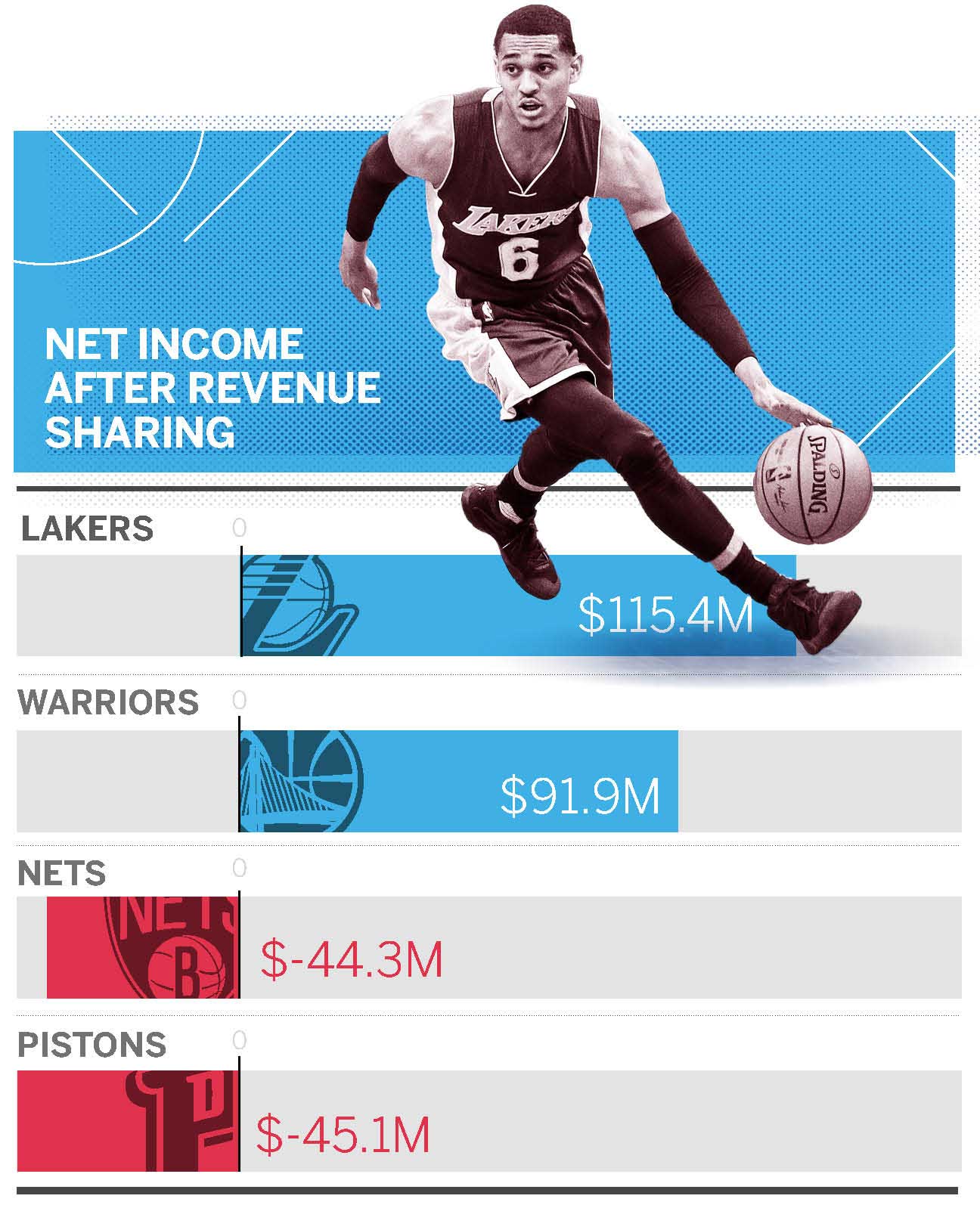

The nine teams that lost money, by the league's accounting for net income (which includes revenue sharing and luxury tax payments), were the Atlanta Hawks, Brooklyn Nets, Cleveland Cavaliers, Detroit Pistons, Memphis Grizzlies, Milwaukee Bucks, Orlando Magic, San Antonio Spurs and Washington Wizards. Sources pointed out that by a different accounting measure the league tabulates -- operating income, which discards various debt obligations -- only 10 teams (rather than 14) lost money before accounting for revenue sharing.

"Teams in small markets are told we need to run our businesses better so we can make money," one ownership source told ESPN.com. "But teams in the largest markets can run their businesses poorly and still make money."

Just how big is the revenue gap?

The NBA's new $24 billion TV deal was believed to be a potential panacea for the league's revenue disparity. But the data from the first year of the deal shows the gap between the have and have-not franchises remains extremely wide.

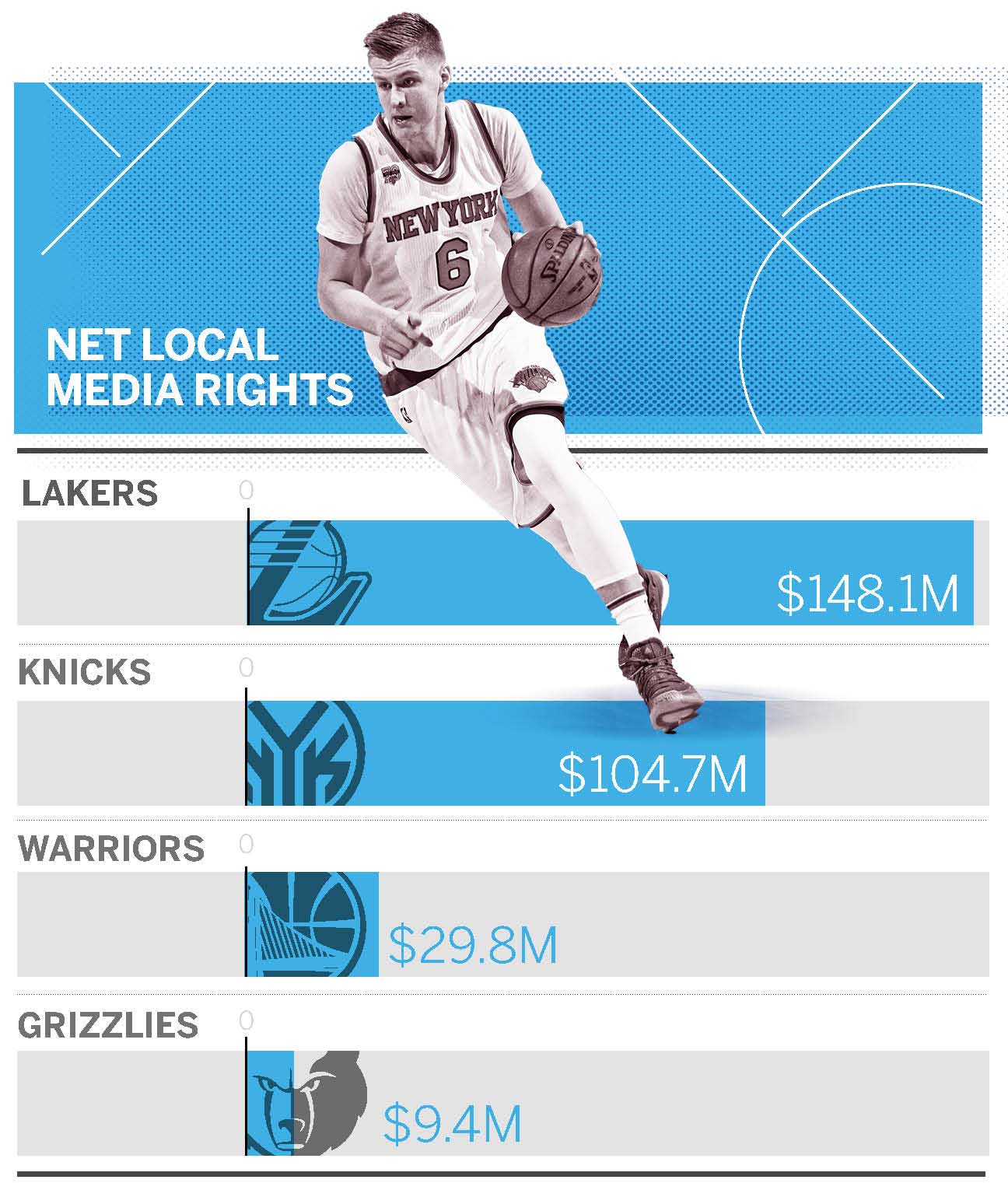

The range of the revenue spectrum is illustrated by the two teams at the opposite ends: the Lakers and Grizzlies. And it's stunning.

In the wake of Kobe Bryant's retirement, the Lakers were devoid of a star player attraction last season for the first time in two decades. To retain their protected draft pick, they tanked the second half of the season, their fourth straight with 27 or fewer wins.

But it was a wonderful season financially. The Lakers finished with a gargantuan $115 million profit as measured by net income even after writing a revenue-sharing check for almost $49 million, according to league accounting. That was the highest net income in the league by nearly $25 million. The biggest factor was the $149 million they took in from massive local media rights deals, primarily with Time Warner.

Four years ago, ESPN The Magazine named the Grizzlies the best franchise in the major sports in its study of 122 franchises, and the team remains highly rated in the annual report. They have molded a strong connection with their fan base behind the "Grit and Grind" marketing campaign and playing style. The Grizzlies have made the playoffs seven straight years and counting.

But it was a tough season financially. After boosting their payroll, the Grizzlies lost nearly $40 million, earning a league-low $9.4 million in local media rights. Their losses were offset by $32 million in revenue sharing, the most in the league. The Grizzlies start a new local TV deal this season that should boost revenue, but as the smallest market in the league by Nielsen rankings, they may continue to have challenges relative to their larger peers.

"National revenues drive up the cap, but local revenues are needed to keep up with player salaries," one owner explained to ESPN. "If a team can't generate enough local revenues, they lose money."

In all, 10 teams transferred $201 million combined in revenue-sharing to 15 other teams in 2016-17, according to the documents. (Five teams -- Toronto, Brooklyn, Miami, Dallas and Philadelphia -- neither gave nor received in revenue sharing. To illustrate how complex the revenue-sharing system is, the Nets are one of the teams that don't receive, despite being among those that lost the most money.) Four teams -- the Warriors, Knicks, Lakers and Bulls -- accounted for $144 million, or 71.5 percent, of those revenue-sharing transfers.

There is broad agreement that the revenue-sharing system is, on the whole, acting as intended, as it shifts money from juggernauts that drive up the salary cap to smaller-market teams that can't approach big-city revenue but have to spend anyway. And the relationship is considered symbiotic to a large degree. According to this argument, the Lakers are a cash machine but need to play teams like the Grizzlies to keep the money rolling in, while revenue sharing helps the Grizzlies stay afloat.

Still, some teams have bristled about the current scale of monetary redistribution. "The need for revenue sharing was supposed to be for special circumstances," one large-market owner told ESPN.com, "not permanent subsidies."

None of this is to say the league is struggling. There is no lockout looming; the league's new collective bargaining deal runs through 2024. Critics of the system want to tweak it, not blow it up.

The 30 teams combined to earn more than $530 million in net income in the 2016-17 season, the documents show. What's more, these numbers focus only on basketball operations; several teams own their arenas, and revenue they generate from hosting non-basketball events is not included in the league's basic financial reporting. For example, the Nets lost about $44 million last season, the documents show, but that doesn't account for revenues from the Barclays Center, which the team's parent company owns.

And as we've seen, NBA franchise valuations continue to soar. Leslie Alexander bought the Rockets for $85 million in 1993 and sold them this month for $2.2 billion. After accounting for inflation, Alexander got more than 15 times what he paid. Driving this value is the fact that the big-market Rockets are a moneymaker; they had $53 million in net income last season, according to league figures.

The players union and its economists have long claimed that teams use accounting techniques to make them appear less profitable than they really are. The union, which is focused on basketball-related income more than teams' balance sheets because that is what determines their split, has the power to review some team's books by conducting its own audit of five teams per season. It rarely exercised that power until 2015. According to several sources familiar with the matter, the union audited five teams for the 2016-17 season. The new CBA will allow it to audit 10 teams, starting this season.

How did we get here?

The new TV deal, worth about $2.7 billion per season, created new challenges only a few teams foresaw -- challenges at the heart of the intensifying revenue-sharing debate.

The salary cap rises and falls in lockstep with overall league revenue; after years of hovering around $60 million, it leapt from $63 million to $94 million over just two seasons thanks to the new TV cash, taking overall player salaries with it.

The league and players union initially projected the cap would quickly rise toward $120 million in annual midsized jumps. Teams splurged on free agents during the unprecedented summer of 2016, when the cap jumped by $24 million, assuming those bloated contracts would be palatable as the cap ballooned.

Those projections turned out to be high. The cap sits at about $99 million for 2017-18, with a small jump to about $102 million currently projected for the following season. Teams that never expected to be around the luxury tax are staring at $100 million-plus rosters and potential tax payments over the next few seasons. Plus, teams are required to have salaries totaling 90 percent of the salary cap, which means a salary floor of $89 million for the upcoming season.

Combined revenue from all 30 teams determines the salary cap, and the biggest teams make the most money -- and therefore drag the cap up for everyone else. Consider the Warriors, who have become a business juggernaut. (They had $92 million in net income last season despite playing in the oldest arena in the league and sending $42 million out in revenue sharing.)

Every Golden State home playoff game generates revenue -- about $15 million a pop in the NBA Finals last season, sources say -- that nudges the cap up a notch for the rest of the league. The Warriors don't get to keep all that money, as playoff revenues are shared with the league, but the documents show they netted $44.3 million from just nine playoff games last season, more than twice as much as the second-place Cavs, who netted $20 million.

The biggest local TV deals also raise the cap level for everyone. The Lakers and Knicks both made more than $100 million from local media deals last season. Only four teams even came within $100 million of the Lakers' local media revenue. The Knicks alone made $10 million more from TV than the six lowest-earning teams combined.

Even Golden State's $20 million-per-year deal (reported by ESPN last week) to wear jersey patches from Rakuten, easily the league's largest such deal so far, has a small impact on the overall salary cap. (The Warriors keep only 25 percent of that money; half goes to the players and 25 percent is shared with the other teams.)

Every team shares equally in the national TV money bonanza, so that has helped offset increased costs. But key sources of local revenue have remained stagnant in some markets, creating an unexpected money crunch. Hence the larger-than-ever revenue sharing, and the tension over that increase.

Is expansion or relocation inevitable?

At least one owner raised the idea of expansion in a recent Board of Governors session, citing the massive expansion fee the 30 current teams would split, sources say. The concept of an expansion fee of potentially more than $1 billion can be tempting because it is not subject to splitting 50/50 with the players.

Adam Silver, the league's commissioner, has repeatedly said the league has no short-term plans to expand, though he labeled expansion at some point "inevitable" during a recent interview in The Players Tribune.

Meanwhile, some profitable teams have bristled at the notion they should share more, and even suggested that teams that lose money every season -- and depend on revenue-sharing to stay afloat -- should consider relocating to stronger markets, sources say.

The concept of changing the placement of teams could become more of a focal point as Seattle nears its decision on a plan to renovate KeyArena or clear the way for a new building to be constructed in the city's SoDo district. A decision could come by the end of the year. If a viable building emerges in Seattle, it could kick-start a deeper expansion/relocation debate within ownership.

Relocation of a different sort is taking place in Detroit. The Pistons lost $63.2 million before collecting revenue sharing last season, the largest loss by a wide margin, despite being one of the NBA's larger markets. (The team received $17.6 million in revenue sharing to help offset the losses.)

Such shortfalls help explain why the Pistons wanted to move out of a building their parent company owned far into the suburbs and relocate to a new arena in downtown Detroit this season, hoping that it helps boost revenue.

And the LA Clippers, in contrast to the Lakers, with whom they share Staples Center, are looking to move locally as well. According to the NBA documents, the Clippers made just $2.1 million in net income last season despite a new media rights deal that paid them $51 million, in part because they make a lot less in arena income (based on tickets and other revenue) than the Lakers.

That was the impetus for owner Steve Ballmer's recent deal with the City of Inglewood to develop a new arena plan if he can't get more favorable lease terms at Staples (the current pact is up in 2024).

Local movement aside, will relocating teams from small markets to larger markets like Seattle clear up some of the NBA's revenue-sharing issues? Will expansion be part of the solution? For now, both ideas appear to be only hypothetical.

Where do we go from here?

While some of the gripes about the revenue-sharing system come from the large-market teams, they are outnumbered, and they're not driving most of the conversation.

There was much jealous eye-rolling around the league when the Warriors announced they would sell their version of personal seat licenses as a barrier of entry to their new arena, which is set to open in 2019.

Some owners have argued that teams should share enough that all 30 finish in the black. Paul Allen, the owner of the Blazers and the NFL's Seattle Seahawks and one of the world's richest people, is among the loudest voices urging more robust revenue-sharing, sources say. One owner even pitched the idea at a recent meeting of the Board of Governors session in Las Vegas that all teams should be guaranteed $20 million in profit, sources said.

There will be pushback to those ideas.

"This is a club where everyone knows the rules when they buy in," one owner told ESPN.com.

Some have even floated the idea of shrinking the amount a team can receive in revenue sharing if it has taken in such payments for several consecutive years, sources say.

Five teams -- Memphis, Charlotte, Indiana, Milwaukee, and Utah -- have received at least $15 million in each of the past four seasons, the documents show.

The revenue-sharing formula is a byzantine maze of calculations based on market size, expected revenue for each team, expense levels and other variables. It includes adjustments that can reduce a team's payout based on various performance criteria. Complicating matters further, team fortunes can fluctuate wildly from year to year.

For instance, the NBA documents showed the remarkable LeBron James effect. In their last season without James, 2013-14, the Cavs received $10.8 million in revenue sharing. Over the past three seasons, the Cavs have paid a total of $29 million into the system. The Cavs made $21.7 million in net income before revenue sharing last season but moved into the red after paying $24.8 million in luxury taxes and $15.2 million in a revenue-sharing check they wrote.

If a team overperforms expectations based on market size and past data, it effectively forfeits some of its revenue-sharing bounty.

That is how the Thunder, playing in one of the NBA's smallest markets, have paid into the system for six consecutive seasons, records show. The Spurs have, too. Meanwhile, the larger-market Nuggets were around the break-even mark by the league's calculations but received an eight-figure check from their partners that pushed them deep into the black. The Nuggets' total expense bill, including player salaries and administrative costs, was the lowest in the league, records show.

The Board of Governors can tweak the revenue-sharing system by a majority 16-14 vote. Between 2011, when this system was installed, and 2014, any change required a supermajority of 20 of the 30 votes, sources say.

Expect several such changes to be the subject of vigorous debate later this month, and going forward.

"It will make for great theater," one team source said.