When legendary point guard Gary Payton is inducted to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame on Sunday, it also will be a triumph for late bloomers everywhere.

In the NBA, where the draft often yields immediate returns, most superstar players are instant contributors. Such were the expectations for Payton, drafted second overall by the Seattle SuperSonics in the 1990 draft after earning consensus All-America first-team honors as a senior at Oregon State. But during his first two NBA seasons, Payton hardly looked like he was on a path to Springfield.

Although he started every game as a rookie -- wearing No. 2 before switching to his trademark No. 20 after the season -- and 79 more in Year 2, the player who would eventually score more points than any full-time point guard since Oscar Robertson averaged less than 10 points per game early in his career.

Payton's slow start is fairly unusual among modern Hall of Famers. Of the 24 NBA players who have been voted into the Hall and began their career after 1977, Payton is one of five to total fewer than nine wins above replacement (WARP) during his first two seasons.

There are explanations for why several of these players started slowly. Petrovic was adjusting to a new country and league and was stuck on the bench behind Hall of Famer Clyde Drexler before a trade gave him an opportunity to show his skills. Mullin, who dealt with alcoholism, broke out after entering rehab during his third season. And Dumars and Pippen were both making the transition from small schools; Pippen already rated better than league average (.500) on a per-minute basis by his second year.

No such easy narrative exists for Payton, a four-year college player given the opportunity to start from day one. In part, Payton clashed with Sonics coach K.C. Jones, a controlling figure who discouraged his point guard from playing to his strengths in transition. During his pre-Hall media tour, Payton told NBA.com he disliked playing for Jones so much he actually considered retirement.

Midway through Payton's second season, Seattle fired Jones and replaced him with George Karl. As fruitful as the Payton-Karl relationship eventually would be, it initially did little to pick up Payton's play, at least offensively. Karl's more aggressive defense yielded more steals for "the Glove," but Payton actually scored less per 36 minutes after the coaching change. He scored double figures just twice in eight playoff games.

As late as October 1992, just before the start of Payton's third season, the Sonics reportedly offered him to the Dallas Mavericks as part of a package for veteran point guard Derek Harper. But after spending the summer working with assistant coach Tim Grgurich, who followed Karl to Seattle, Payton returned a different player. He improved both his usage rate and his efficiency and helped the Sonics reach within a game of the NBA Finals.

By Payton's fourth season, he was an All-Star. By his sixth, he was part of Dream Team 3, earning a spot on the 1996 U.S. Olympic roster after the Sonics lost to the Chicago Bulls in the NBA Finals. Yet his improvement would continue. With Grgurich's help, Payton rebuilt his jumper. After making 26 3-pointers in his first four seasons combined, Payton would make at least 70 each of the next eight seasons and lead the league in triples in 1999-2000.

Payton's best play would come after Karl and running mate Shawn Kemp were gone and Kemp's replacement, Vin Baker, battled weight and alcohol issues. That left Payton as the lone star trying to carry a young Sonics team to the playoffs. He pushed his usage to newfound heights while maintaining his assist rate, creating more offense than anyone else in the league. In 1999-2000, between points and assists, Payton was responsible for producing 42 percent of the Sonics' points, far and away the NBA's highest total (Stephon Marbury was second at 36 percent).

At age 30, Payton posted a career-high 20.0 WARP after the lockout (that figure is prorated to 82 games). He was almost equally as good the season before and the following season. In fact, Payton's three-year total of 58 WARP from ages 29-31 is surpassed by just four players since 1977-78: Magic Johnson (69), Larry Bird (66), Hakeem Olajuwon (64) and John Stockton (62).

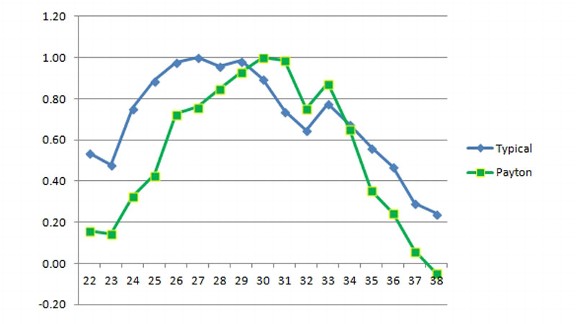

Among the group of Hall of Famers who began their career after 1977, just Dumars (33), Karl Malone (33) and Dominique Wilkins (31) peaked in terms of value later than Payton. Comparing his career path to the typical post-merger Hall of Famer, who top out at about age 27, shows Payton started much slower but continued developing much longer.

Of course, Payton couldn't entirely defeat Father Time. After the Sonics dealt him to the Milwaukee Bucks at the 2003 trade deadline, Payton's production dropped off quickly. While his post-Seattle career featured two more trips to the Finals and a long-desired championship as a reserve on the 2005-06 Miami Heat, it ended up with him dipping below replacement level during his 17th and final season.

Still, Payton's unusual career path offers hope to high draft picks who struggle early in their careers. There's still time for them to improve and join Payton in Springfield someday.