Cliff Welch/Icon SMI

Cliff Welch/Icon SMI

Holding out on history

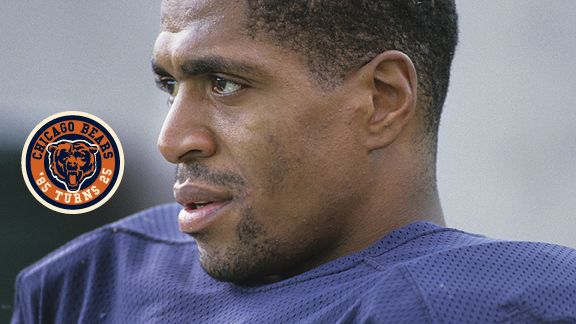

Todd Bell missed '85 season, as one of several Bears embroiled in contract disputes

Years later, Daphne Bell asked her husband if it was worth it. If missing the Super Bowl for some long-forgotten principle on the advice of an agent he would later fire still bothered him.

"Obviously, Todd didn't know what was at stake," Bell said. "He didn't know they were going to the Super Bowl that year. But he said to me, 'What if I did come back? Then I would become someone I wasn't. I could not compromise my principles because if I don't stand for something, it will hurt the next player.'

"It cost him a lot, but in the big scheme of things, he could sleep at night and look himself in the mirror the next day, even if it was with a tear in his eye. I respected him so much more than if he was MVP of the Super Bowl."

Game off the field

The Chicago Bears were 4-0 in the first week of October 1985. Their defense was quickly establishing itself as the best in the NFL, and the rest of the country had already taken notice of a team with the greatest collection of happy-go-lucky characters in all of sports.

But inside Halas Hall, angry phone calls, simmering threats and general discontent had taken hold.

On Aug. 1 in Platteville, Wis., a week and a half into the team's training camp, six Bears regulars and one future starter were at home, still mired in contract standoffs. Two months later, as the Bears readied to take on the Buccaneers in Tampa, Fla., Todd Bell, who was a contract holdout with linebacker Al Harris, asked to be traded. Defensive end Richard Dent said he would do the same, if his contract problems could not be worked out soon.

Eight years before free agency as we know it today, the players' options were limited. Today, 25 years later, Dent, the eventual MVP of Super Bowl XX, cannot hide his bitterness.

"The entire 11, 12 years I was there, walking through the doors at Halas Hall was like walking through fire," Dent said recently. "I didn't ask to come here but to me, this should be a dream story. A black kid from a small black school going from [expletive] to sugar overnight. But whatever it was, to me, no one there wanted to appreciate it. Why do I have to fight for something when you drafted me way down here [in the eighth round, 203rd overall, in the '83 NFL Draft], and I turn out to be a blue-chipper?

"To me, it was like slavery. I didn't have any chance to go work anywhere else. It was either work for the Bears or work for nobody, and there is nowhere in America where a person does not have a choice to work somewhere else, to give your service to who you want. To me, I didn't have a choice."

Dent and his agent were negotiating an extension to his contract, which was to run through the '85 season and pay him $90,000, but Dent, who like fellow training camp holdout Mike Singletary was under contract that preseason, eventually decided to play through the impasse.

First-round draft pick William Perry and veterans Steve McMichael and Keith Van Horne -- all unsigned before the season -- also reported to camp eventually. But not everyone received a warm and fuzzy reception.

Perry ended his contentious holdout on Aug. 5, when he signed a four-year, $1.35 million contract, one week after Bears general manager Jerry Vainisi declared, "I'm not planning on William Perry playing with the Bears this year."

Two days later, after muscle cramps kept Perry out of practice, defensive coordinator Buddy Ryan uttered the infamous words, "It's a wasted draft choice and a waste of money.

"We should have given the money to Todd Bell and the pros we know who can play, and brought them to camp."

Bell, who played for $77,000 the year before in a Pro Bowl season,was a Ryan favorite, but Bell was asking for $950,000 annually, which would have made him the highest-paid player on the team. The two sides were $166,000 apart, and Bell held firm to his agent's insistence that he be paid his market value.

There was no questioning his value to the Bears.

“Todd was a vicious hitter, a great team player, and it was really hard to believe that was actually happening, that here you had this team with a real chance to do something and that we were not going to have our All-Pro safety.

” -- Gary Fencik

"You talk about when things changed for the Bears," said Bell's fellow starting safety Gary Fencik. "Well, fortunes changed for the Bears on one hit by Todd Bell on [Redskins' running back] Joe Washington in the second quarter [of the '84 NFC Playoffs] in Washington."

Bell's teammates and astute fans remember the ferocious signature blow that did not just flip the momentum of the game but arguably altered the standing and course of the Bears' franchise. It was one more reason the absences of Bell and Harris the following season were so hard to take.

Fencik, who at one point went to Bears president Michael McCaskey to try to expedite the Bell and Harris negotiations, remembered the feeling of helplessness.

"Todd was a vicious hitter, a great team player, and it was really hard to believe that was actually happening, that here you had this team with a real chance to do something and that we were not going to have our All-Pro safety," Fencik said. "Once we were into the season, it was clear it was a stalemate, and the only one that was going to win this one was Todd if he came back. But he was very adamant."

Vainisi recalled the close relationship he had with Bell and Harris, and called the failed negotiations "one of my dark memories as general manager."

To tell you the truth, I don't think I ever got over it," Vainisi said

Vainisi said he simply ran out of time to get the deals done in the window required, and without the commitment of Bell's agent to come to an agreement. Vainisi told of the time Bell's agent sent him an 18-page proposal in which he failed to change the name of another client in all but the first paragraph.

Vainisi said he eventually negotiated with the fathers of Bell and Harris because "I just wanted to talk to them as fathers and not as a general manager. I wanted to find any way I could to break the stalemate."

But in the end, it was still a negotiation.

"Al Harris' father felt that Al had beaten out Wilber Marshall the year before and that he should be paid accordingly," Vainisi said. "But he really didn't beat him out. That was Buddy's way of hazing a rookie. The only rookie who ever started for him was [Dan] Hampton. But Mr. Harris couldn't see that.

"For a short period of time, Wilber was the highest paid player on the team (having signed a contract worth then a whopping $492,000 a year due to leverage from being drafted by the USFL, a league that closed its doors in '86). So Mr. Harris felt Al was entitled to a dollar more than Wilber. Al would not go against his father and his father was locked into a dollar or more."

Vainisi said the emotional aspect of the negotiation was the worst part.

"I knew what Todd and Al were missing and I kept telling them this was going to be a special year," he said. "Anything short of winning the Super Bowl was going to be a disappointing season and everybody was totally committed to that one goal. . . . Al is a wonderful person and so was Todd and that probably bothered me as much as anything. They deserved to be on that team. They were an integral part of that team, and it was just unfortunate they weren't able to partake."

For Vainisi, the Bell and Harris' talks took up only a portion of his agenda. The Dent talks were going nowhere, and frustration that began the previous summer came to a head in Week 5 of the regular season when Dent first mentioned the "T" word.

Vainisi, now chairman of the board and CEO of Forest Park National Bank & Trust Co., sounded frustrated when discussing the Dent situation.

"[Everett Glenn, Dent's agent] never seemed to get focused on where we had to go to get the job done," Vainisi said. "We had agreed to a contract two or three times, and he reneged on the deal. It was just a joke and so sad that negotiation, it really was."

Dent, who felt equally sad that he was unappreciated, said playing through the contentious negotiations fueled him.

"But mostly the guys fueled me," he said. "The guys and the town and the love of the game fueled me. How much more could they have gotten out of me? Who knows if one felt like they were appreciated?"

Dave Duerson did not necessarily feel appreciated either. But for the strong safety who, with Marshall, repalced Bell and Harris in the starting lineup, '85 was an opportunity to prove himself. With four consecutive Pro Bowl appearances at both safety positions going into the Super Bowl year, Duerson did prove himself, despite the treatment he received from Ryan.

"There was not a day Buddy Ryan didn't make me aware of [his faith in Bell] on some level because I was not his choice," Duerson said. "But I had absolute respect for Todd, whether it was principle or economics or whatever it was, I respected the fact that he was standing up and drawing a line in the stand."

Shortly after Bell signed a new contract following the season, the two went to dinner, Duerson said.

"Todd said, 'I just want you to know I have no hard feelings toward you,'" recalled Duerson, who started ahead of Bell in '86 before moving to free safety so Bell could start at strong in '87. "I told him thanks and how much I appreciated it. And I said, 'Just so you know, I was coming after your job or Gary's.'"

'Learn from me'

Years later, Daphne got some insight into how her husband coped with missing the most magical of football seasons.

"You can't unring a Bell, that's how Todd lived," she said. "If he heard on the news about a young player in a contract dispute, he used to find a way to call and tell them, 'I understand how you feel but learn from me. Remember my story and take my advice. Go in, get your money and go home.'

"He wanted them to understand what they were sacrificing. Are you willing to stand by your sacrifice? If not, re-think this thing because you have to look yourself in the mirror and live with it."

Bell retired from football in '89 after playing two years under Ryan for the Philadelphia Eagles. He has since devoted himself to a life of charitable endeavors and good deeds.

He created and ran a program at his alma mater, Ohio State, with the goal of increasing the rate at which African American males return to the university to complete their degrees. Todd and Daphne also founded an organization called Builders of Dreams for Youth in which they reached out to troubled students and gave them incentives for staying in school and improving their grades.

Bell coached high school football and mentored at-risk males in Columbus area high schools, facilitated a young scholars program at OSU and was the director of several youth organizations.

Daphne said Todd "never once cried or whined" about missing out on the championship season, and he told her he couldn't be bitter.

"Todd loved football, he loved the organization, and he loved Chicago," she said. "It was home to him. He was really disappointed because he had grown to be attached to the organization and to the city. It's why he wanted to be buried in Chicago."

“Todd is most remembered for his holdout but no one really knows why he held out Everyone put a dollar sign on it, but there was so much more to it than that for Todd . . .

” -- Daphne Bell

Sadly, Todd's death at the age of 46 from a heart attack while driving to one of his daily workouts came way too soon on March 16, 2005. At the time of his death, he looked as if he could suit up and pop some receivers coming across the middle. He was the picture of health. Daphne sent her husband's autopsy report to a specialist, who determined that Todd was in the beginning stages of heart disease.

Todd had been to a doctor three weeks before his death and was advised to get a heart scan, which he planned to do. "The specialist said all he needed was stents in his chest, and he would have lived happily ever after," Daphne said.

She has since created a foundation in Todd's memory called "Keeping TABS (for Todd Anthony Bell) on your Heart," which enables uninsured men to have genetic histories and testing done to detect the type of condition that caused her husband's death.

That program at OSU that Todd created to mentor, tutor and encourage African American men to return to school is now called the Todd Bell Resource Center, and the retention rate at the school has since soared.

Daphne has written a book, "The Pain Didn't Kill Me" about her relationship with Todd and the value of life.

"Todd is most remembered for his holdout, but no one really knows why he held out," Daphne said. "Everyone put a dollar sign on it, but there was so much more to it than that for Todd. . . The holdout was so minute in the whole scheme of things. It doesn't even make it on the scale, because at the end of day what does it really matter?"

Melissa Isaacson is a columnist for ESPNChicago.com.