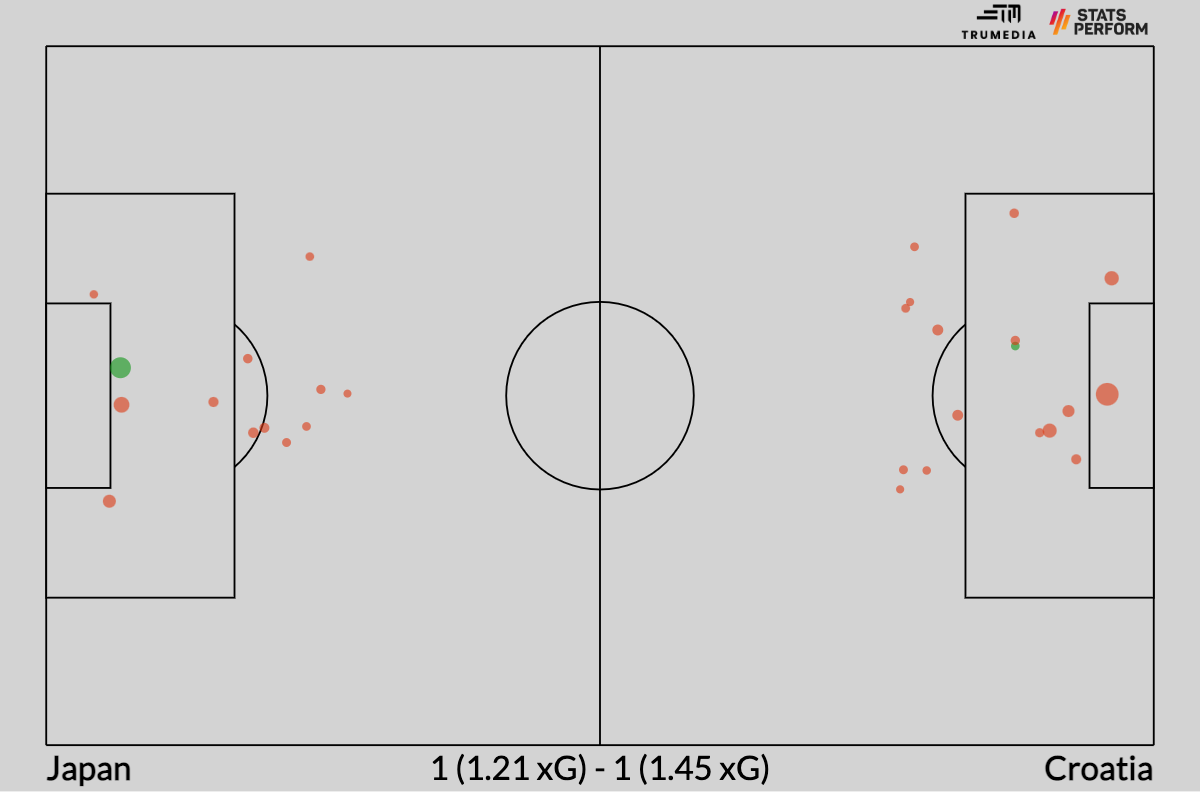

On Monday, Croatia and Japan played to a 1-1 draw across 120 minutes and over those two hours of soccer, the match was just about as even as it can possibly get. Croatia attempted more shots (17 to 14) and controlled more of the ball (58% possession), but as they have been all tournament, the Japanese were much more efficient in turning that limited possession into a collection of quality chances.

Based on expected goals, which estimates the conversion probability of every shot attempted in a match based on massive dataset of historically similar shots, this really was one of the closest games of the tournament:

That is... until you got to the shootout. Two teams with seemingly nothing between them entered into what's supposed to be a complete crapshoot tiebreaker -- and the result seemed obvious from the start. Takumi Minamino hit a meek penalty, easily saved by Dominik Livakovic, and then Nikola Vlasic smashed his spot-kick past Shuichi Gonda to put Croatia ahead. The rest of the shootout roughly followed that same pattern and Croatia were eventually through, 4-1.

- World Cup news, features, previews, and more

- Stream FC Daily and Futbol Americas on ESPN+

The result marked Croatia's third straight penalty-shootout win at the World Cup. In fact, Croatia have never lost a World Cup shootout. Is there something special going on here? Or is it just that if you flip a coin enough times, you're bound to see it land on heads or tails a couple of times?

With the quarterfinals kicking off Friday, here's everything you need to know about penalty shootouts -- you know, the thing that could well decide who wins the World Cup.

How often do penalties get scored?

Since the 2010-11 Premier League season, there have been 1,397 penalties attempted and 1,094 scored. That comes out to about a 78% conversion probability, so that's roughly what to expect whenever any top-level professional player steps up to take a penalty. He's going to score slightly more often than three out of every four times.

Across the entire quantified history of the World Cup, which goes back to 1966 thanks to Stats Perform's data collection, that number is even slightly higher: 176 out of 220, or about 80%. Perhaps some of that is due to the gulf in quality in earlier tournaments -- better teams were more likely to win penalties and then convert them against worse sides -- but maybe it's just a minor difference across a relatively small sample of attempts.

Since the tournament expanded to 32 teams in 1998, the conversion rate at each tournament has tended to fluctuate wildly. See if you can figure out when they first started using VAR:

1998: 17-for-18 (99%)

2002: 13-for-18 (72%)

2006: 13-for-17 (77%)

2010: 9-for-15 (60%)

2014: 12-for-13 (92%)

2018: 22-for-29 (76%)

With eight games to go at this year's event, 16 penalties have been awarded and 11 have been converted for a 69% success rate.

OK, but I want to know about shootouts!

Good eye: everything you just read pertains only to penalties that occur over the course of a given match, whether it be regulation or extra time. It's a larger sample size, but I needed to set the table for what comes next.

In World Cup shootouts, the penalty conversion rate drops all the way down to 69%. There have been 294 shootout shots so far at the World Cup, and 203 of them ended up in the back of the net.

So, what gives? The easiest explanation is that your best penalty taker will almost always take your penalties during a match, but then he gets to take only one during a shootout. Research from Stats Perform seems to back this up, too. The conversion rates for each of the first six shooters are as follows through 2018:

First: 75%

Second: 73%

Third: 73%

Fourth: 64%

Fifth: 65%

Sixth: 50%

At the same time, pressure presumably increases the deeper you get into the shootout. It's rare that any of the first three are a "must make," meaning that if you miss the penalty, then the shootout is over. That could help to explain the large drop-off from the third to the fourth shooter. In fact, according to other research, only 62% of the penalties to extend a World Cup shootout were converted, while a whopping 92% of the penalties to win a World Cup shootout were converted.

I don't believe that the difference between a team's first- and fourth-best taker is as large as these numbers show -- I'd guess it's only a percentage point or two -- so "pressure" probably explains the rest of the discrepancy.

All right, so how often do we get to see one of these things?

Penalties were first introduced in the 1978 World Cup, but it was a 16-team tournament that featured only two knockout matches, one of which went to extra time and none of which went to penalties. Somehow, all 42 knockout-round matches between 1954 and 1974 were decided by the end of 120 minutes. The structure of the 1950 tournament didn't include knockout matches, and there were no tournaments before that and back through 1938 because of World War II. But across the 1930, 1934 and 1938 tournaments, there were 35 knockout games, with 31 of them decided after 120 minutes. As for the other four? They didn't have a shootout. No, they just replayed the entire game on another day.

From 1978 through 2018, though, there were 150 knockout-round matches and 30 of them went to penalties, or exactly 20%. Of those 150 matches, 51 (34%) went to extra time, so more than half (59%) of the matches that reached extra time ultimately extended all the way through to a shootout.

With 16 knockout matches this tournament, we were likely to see about five or six go to extra time and four head to penalties. Halfway in, we've seen two matches extend past 90 minutes, and they both went to a shootout.

Who's the best at them? Must be Messi, right?

No! Converting penalties might be the one thing Lionel Messi isn't good at.

One of the fun developments from the increasing quantification of what's happening on a soccer field is that it has shown just how great the greatest soccer player of all time actually is. Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo might be neck-and-neck in terms of goals scored, but Messi is also better at creating assists than anyone else. He's better at completing through-balls. He's better at passing into the penalty area. He's better at passing the ball upfield. He's better at dribbling. Heck, he's better at walking.

He's also better at finishing than anyone else. Across every game Messi has played for Argentina, Barcelona and Paris Saint-Germain in the Stats Perform dataset that goes back to 2010, he has scored 518 goals on 3,201 non-penalty shots, which comes out to a 16.2% conversion percentage. Across Spain's LaLiga over the same stretch, the non-penalty conversion rate is 10.2%. Given how small the numbers are, that's a massive difference.

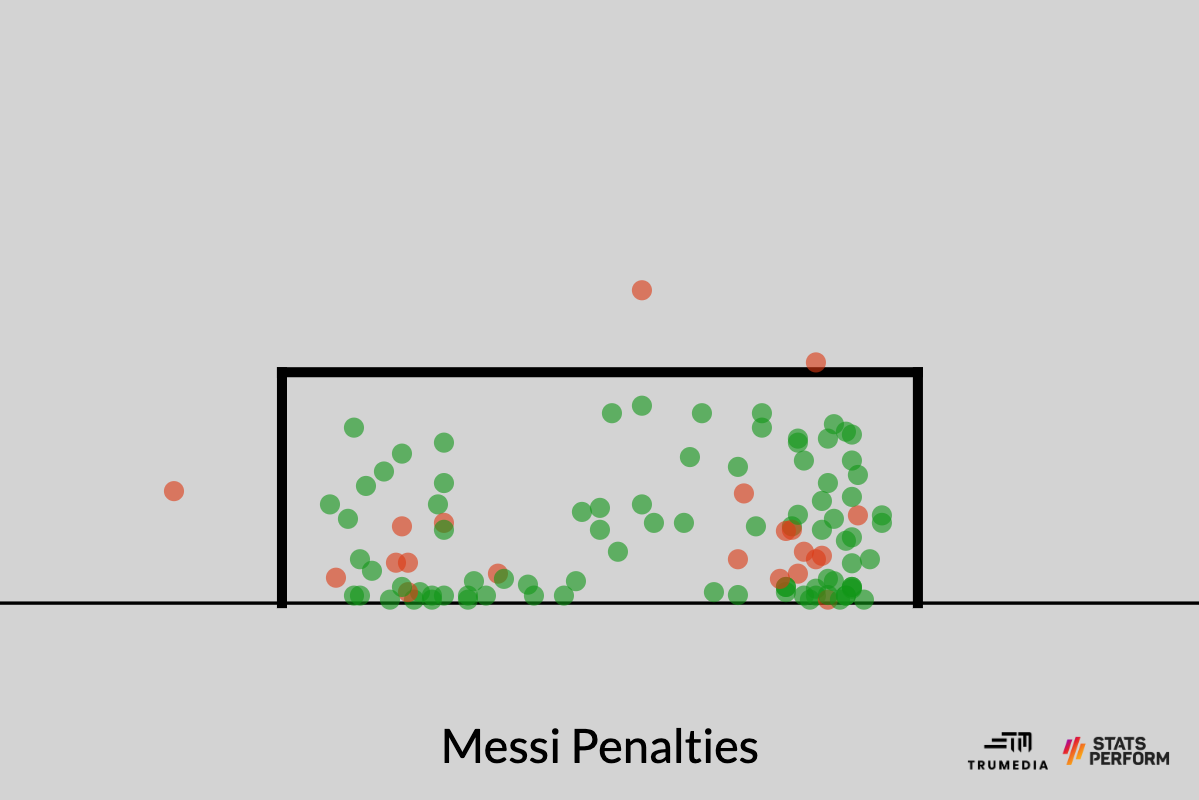

However, Messi has had 108 penalties coded into the Stats Perform data and converted 86 of them into goals -- or 79.6%, right around the average we went over earlier.

It's baffling that Messi could be so good at striking a ball -- he's also the world's best free kick taker! -- but not be better than average from the spot. Interestingly, the economist Ignacio Palacios-Huerta found that there's actually zero correlation between a player's salary and his penalty-conversion rate. To me, this speaks to how little your comparative skill of being able to kick a ball accurately goes into goal-scoring, but that's a conversation for another day.

So who is good at them?

Among players who are still at the World Cup and have attempted at least 20 penalties in the Stats Perform dataset, France's Olivier Giroud and Brazil's Fabinho lead the way with 22 of 24 converted at a 91.7% clip. Here's the rest of the top 10:

3. Bruno Fernandes, Portugal: 40-for-44 (90.9%)

4. Harry Kane, England: 56-for-64 (87.5%)

5. Paulo Dybala, Argentina: 27-for-31 (87.1%)

T-6. Steven Berghuis, Netherlands: 26-for-30 (86.7%)

T-6. Jordan Veretout, France: 26-for-30 (86.7%)

9. Andrej Kramaric, Croatia: 28-for-33 (84.8%)

10. Teun Koopmeiners, Netherlands: 33-for-39 (84.6%)

Of those 10, half of them -- Fabinho, Dybala, Berghuis, Veretout and Koopmeiners -- don't seem likely to start their next matches, but don't be shocked if their managers find to get a way to get them out there before the 120 minutes are up.

One player who will definitely not be out there, though, is Ivan Toney, who could've represented England... but has since been charged with, um, 232 violations regarding betting rules. Among all the players in the dataset, Toney is the only one to attempt 20 penalties (or more) and not miss a single one.

At the other end of the spectrum, France's Antoine Griezmann (21 for 32, 65.6%) and Wout Weghorst of the Netherlands (17 for 25, 68%) are the only remaining players in the field with at least 20 penalties attempted and a conversion rate below 70%.

Do the better players do anything special?

Penalty-taking analysis is rife with pseudoscience -- things like looking at the posture of a player as he approaches the ball and claiming it has some kind of connection with his likelihood of kicking the ball into the net. I'm sure if you went and tracked all of the astrological signs for each kicker and keeper and then connected it with what time of year the penalty happened you'd be able to find some kind of tenuous connection with the data, too.

The main problem with all of this is that it's purely result-based: we're working back from what the outcome of the penalty was to then try to explain why it happened, rather than trying to isolate any controllable factors that tend to lead to penalty goals more often and then seeing which players are best at doing that. But even that is hard to do because there's also a little game between the keeper and the taker, so sometimes a softly hit penalty down the middle is a terrible process, while other times -- if that taker gets the keeper to dive early -- it's essentially a guaranteed goal.

So rather than dipping into whether you should pause before you shoot or stutter your run-up or hop up in the air before kicking or lick your fingers and pat down your eyebrows before slaloming toward the ball, let's just try to keep it simple: kicking it higher is better.

According to an analysis of 536 penalties attempted in the Champions League and Europa League highlighted by Ben Lyttleton, who literally wrote the book on penalties, 82% of high penalties turned into goals while only 70% of low penalties were converted. Interestingly, high penalties missed the goal way more often -- 13%, compared to 2.7% of low shots -- which makes sense since you can't, you know, kick the ball under the goal line.

However, it suggests that players should be more willing to risk the ignominy of skying one over the bar because it'll make them more likely to score over the long run. In other words, justice for Roberto Baggio.

The other thing that players should do is change where they're aiming across the goal at random. Maybe you still want to go high, but you don't want there to be any tendencies for the opposition coaching staff to pick up on. It's practically impossible for the average person to purposefully act randomly, but according to early research from Palacios-Huerta, most penalty takers do actually select their locations at random.

Professional athletes: they're not like us!

And keepers?

It's the same thing. There's some research that contends that acting like a circus performer on the line or messing around with the ball so the player has to delay his attempt will lead to a decrease in penalties being scored. Much like the other analyses I mentioned earlier, I do not consider this to be scientifically rigorous analysis.

Some teams have better penalty prep, some keepers have an ability to pick up on tells better than others, some are just better at saving shots, and some have just faced a bunch of good or bad penalties over their careers. So rather than trying to draw any kind of lessons here, I'm just going to list the save rates of all eight starters against regular and shootout penalties.

Before we get there, some base rates: the save rate on World Cup penalties is 13.7%, while the save rate in shootouts leaps all the way up to 24.5%. Now for the eight guys left:

Hugo Lloris, France: 11 saves on 87 PKs (13.4%); 0-for-13 in shootouts (0%)

Jordan Pickford, England: 9 saves on 38 PKs (17.6%); 6-for-25 in shootouts (24%)

Yassine Bounou, Morocco: 5 saves on 37 PKs (15.2%); 2-for-7 in shootouts (28.6%)

Alisson, Brazil: 8 saves on 35 PKs (26.7%); 2-for-30 in shootouts (6.7%)

Emiliano Martinez, Argentina: 7 saves on 30 PKs (25%); 7-for-26 in shootouts (26.7%)

Diogo Costa, Portugal: 4 saves on 13 PKs (36.4%); 0-for-5 in shootouts (0%)

Dominik Livakovic, Croatia: 1 save on 10 PKs (10%); 3-for-4 in shootouts (75%)

Andries Noppert, Netherlands: 0 saves on 1 PK (0%); 0-for-0 in shootouts

The site FBref has additional data for Noppert in two seasons he spent in Italy's second division, where he faced two penalties and saved one, so we can bump that number up to 1-for-3 (33.3%). At the 2014 World Cup, current Netherlands manager Louis Van Gaal brought on a specialist penalty keeper Tim Krul for both of their shootouts, so perhaps we'll see something similar if they get there again.

One last point: Bounou didn't give up a goal in the shootout against Spain in the round of 16 -- two saves and one miss -- but he was 0-for-4 in shootouts before that.

One last thing: What if you win the coin toss?

Palacios-Huerta's research also found that the team that shoots first in the shootout wins 60% of the time. This would seem to play into the pressure effect; if you shoot first, you're a little freer because the other team hasn't scored yet, and then if you score, you immediately push all of the pressure onto your opponent.

If you accept that penalties should be 50-50, then a team that wins the toss and elects to go second is passing up a 10% edge. I don't think there's any other kind of individual coaching decision across a single match that could increase your win probability by that much, so it's essentially managerial malpractice to leave it on the table.

However, at the World Cup, this pattern just hasn't held true. Accounting for the Croatia-Japan game, there have been 31 shootouts in tournament history, and 16 of them... were won by the team that shot second. But even if these findings don't apply to the World Cup or no longer properly project at the highest levels of professional soccer, then you might as well still go first, right?

Best case, you're giving your team a slightly better chance of winning. Worst case? It's back to being a coin flip.