Here is what we've learned from the Club World Cup thus far:

The Bundesliga is a lot better than the Northern League of New Zealand. The Portuguese league is also better than New Zealand's league, but not by as much -- and it's also worse than MLS. But MLS is worse than the Tunisian league. And the Tunisian league is worse than the Brazilian league, but that's nothing to worry about because the Brazilian league is better than the Premier League and the Champions League. As for the Saudi Pro League, Spanish LaLiga, Italian Serie A and Mexico's Liga MX? They're all pretty much the same level.

If you knew nothing else about soccer and just scanned the results from the first week of matches, you could at least convince yourself of all those things: Botafogo beat Paris Saint-Germain, Flamengo beat Chelsea, Al Hilal drew with Real Madrid, Inter Miami beat FC Porto, and Inter Milan drew with Monterrey. Oh, and Bayern Munich beat a bunch of New Zealand part-timers, Auckland City, 10-0.

But those takeaways, of course, are not quite true. Were they true, we'd likely already see those shifts reflected in the betting markets. And, per ESPN BET, the five biggest favorites to make it to the final are teams from the world's five biggest leagues: Germany, Spain, England, Italy, and France.

But I'm also not sure that we haven't learned anything, either.

The atomized landscape of professional soccer makes it hard to really know anything about how one league compares to another. Sure, the Premier League is very likely the best league in the world because its teams make significantly more money than everyone else, but even just among those Big Five leagues in Europe, we don't really know where, say, Atlético Madrid would finish if they played in England, or how Brentford would perform in the German Bundesliga.

Stretch beyond Western Europe and it gets even murkier. MLS? Yeah, it might be somewhere between the ninth-best and the 35th-best league, depending on how you define the terms and whom you ask. Could the titans of South America -- the likes of Flamengo and River Plate in the region -- hang across a full season in a Big Five league? And really, what the heck happens when you create a Frankenstein's monster of a team -- a roster half-filled with above-average European pros and half-filled with guys from the country that's currently 58th in the FIFA rankings?

To get close to answering these questions, we simply need more games. And while there is plenty lacking from the Club World Cup -- top teams, fans, television ratings, a reality-based understanding of the world from the guy in charge of FIFA -- there is absolutely one thing we can all agree this tournament is providing: games. Sixty-four of them, in fact.

So, come mid-July, could the Club World Cup actually teach us something about how soccer works?

Comparing league strength vs. league translation

Even with a bad knee and an aging body, if I showed up to a random pickup soccer game in, say, Bangor, Maine, and you watched me play, you'd think I was really good at soccer. As a former mediocre Division I player, I still am better at soccer than a large majority of the American population. If you dropped, say, a League One star from England into a random Atlantic 10 game this upcoming fall, you'd think he was really good at soccer. If you dropped a solid Premier League starter into League One, you'd think he was really good at soccer.

The problem, in each of these situations, is that you have no idea exactly how good any of these people are because of the contexts in which you're seeing them play. While each example is somewhat extreme, the same idea applies between any two leagues or competitive contexts across the world.

If you're scouting players, it's crucial to understand these contexts. It can help you avoid overvalued players who look great in a league that might boost performance but doesn't translate well elsewhere.

Learn how Nicolas Jackson's sending off helped Clube de Regatas do Flamengo beat Chelsea 3-1 in the FIFA Club World Cup.

The Dutch Eredivisie is the canonical example, filled with canonical individual examples. In his age 21 and 22 seasons with Dutch side AZ Alkmaar, Jozy Altidore scored 38 goals and added six assists. Then he signed for Sunderland in England and scored one goal -- in two full Premier League seasons. Altidore's speed and physicality played up in the wide-open, less-physical Dutch league, but his impact suddenly wilted when faced up against bigger and faster players in smaller spaces.

However, the reverse can also be true: There are undervalued players in unfairly maligned leagues. Back when they were also owned by Brentford's Matthew Benham, FC Midtjylland signed lanky Finnish midfielder Tim Sparv from Greuther Furth in Germany's second division. Sparv was 27 at the time, and Greuther Furth had finished in third place in the 2.Bundesliga. Outside of maybe a few Danish reporters, no one thought anything of it.

But this signing was quite interesting for two reasons. The first is that Midtjylland signed Sparv not because they liked watching him play, but because their in-house statistical model said they should. "It was something new and foreign to me," Sparv told me. "I was bought because of stats and data."

The second interesting thing is what the statistical model actually said.

Based on a cross-section of games between different leagues in various domestic and continental cups, Midtjylland felt that the German second division was severely undervalued. They also felt that Greuther Furth's results were unluckier than their underlying performances. And on top of all that, they found that the team played worse when Sparv wasn't on the field.

"In their eyes, the league was undervalued compared to others, so they felt like, 'OK, we can find some gems in this league,'" Sparv said. "We were doing really well back then. I was playing and doing fine myself. They could see, 'OK, this is someone we like,' and also that when I was in the team, we were winning more than when I was not playing."

Sparv went on to win three league titles in Denmark -- the first three Midtjylland had ever won -- and he captained the team in its 2-1 UEFA Europa League win over Manchester United in February 2016.

Another source who works in one of Europe's Big Five leagues told me that a large part of the reason his team excels in acquiring talent is because it's better able to translate contexts than most of its competitors. Interestingly, he added that league-to-league translation isn't quite the same as league-to-league strength. Figuring out whether or not a player will do well if he moves from League A to League B isn't the same thing as trying to figure out whether a team from League A or League B is more likely to win a given game.

What the Club World Cup could teach us

Both Midtjylland and my other source's club have access to much more advanced data than is available publicly. They're able to analyze league translations and league strength by looking at the handful of games where there's cross-competition pollination. Perhaps by using more fine-grained datasets that include things like tracking data, they're also able to mine some cross-continental information out of national team games -- even if that's a wildly different context to what we see in almost any major league.

Throw it all together with the right philosophical assumptions and savvy data science, and you can probably make some reasonably confident predictions as to which league is better than which, and which players might scale up to whatever league you're playing in.

But whatever your dataset, the thing that would make all of this way easier -- and the thing that helps fans understand what they're watching -- is more games between teams in these different leagues.

"The Club World Cup historically has been the only competitive competition across continents, but the sample of matches has typically been very small, only eight a season," Aurel Nazmiu, senior data scientist at the consultancy Twenty First Group, told ESPN. "The 2025 Club World Cup is going to give us eight times more matches (64) to better understand team performance globally."

Stevie Nicol believes fans are struggling to back the Club World Cup as attendances remain relatively low.

Twenty First Group maintains a global team-rating system that also doubles as a global league-rating system. Coming into this tournament, it rated the Brazilian Serie A as the sixth-best league in the world and Flamengo as the best non-European team. Again, it did this before the tournament, and the prediction seems pretty accurate based on what we've seen so far.

MLS, meanwhile, entered the event ranked as the 32nd-best league in the world. That will seem low to many fans and followers of the league, but when a rating system depends on cross-pollination, your league isn't going to rate well when your league never really beats teams from other leagues. While we're talking about relatively complex algorithms here, there is a "shut up and win the darn games" aspect of all of this, too.

Now, perhaps Inter Miami's performance at the Club World Cup will boost the league's standings in these global rating systems -- or maybe LAFC's relatively unimpressive showing will cancel it out. But there is one problem with these games: The data might be corrupt. Put more plainly, we don't actually know how hard any of the biggest teams are trying in any given match.

The overall winner of the Club World Cup will win a cash prize of up to around $125 million -- more than the roughly $100 million on offer to the winner of the UEFA Champions League, and dwarfing the roughly $30 million for the winner of the Europa League. But money can't buy prestige -- or at least it hasn't so far -- and the Club World Cup lacks the reputation or fan enthusiasm that the UEFA Champions League has.

"There is a big question mark around how seriously teams will be taking this competition, especially European ones," Nazmiu said. "The financial rewards on offer certainly provide incentive for teams, but given this tournament is taking place in the summer after a long European season where a number of players also participated in the Euros last summer means there's a risk some players lack motivation.

"As the tournament progresses we'll begin to get a better sense of this, but for now it's worth being mindful and not overcommitting to what individual results mean for global quality. Tournament football is much noisier than league football: The best teams typically win the league given it's over a longer period of time, whereas in knockout tournaments there's more surprises."

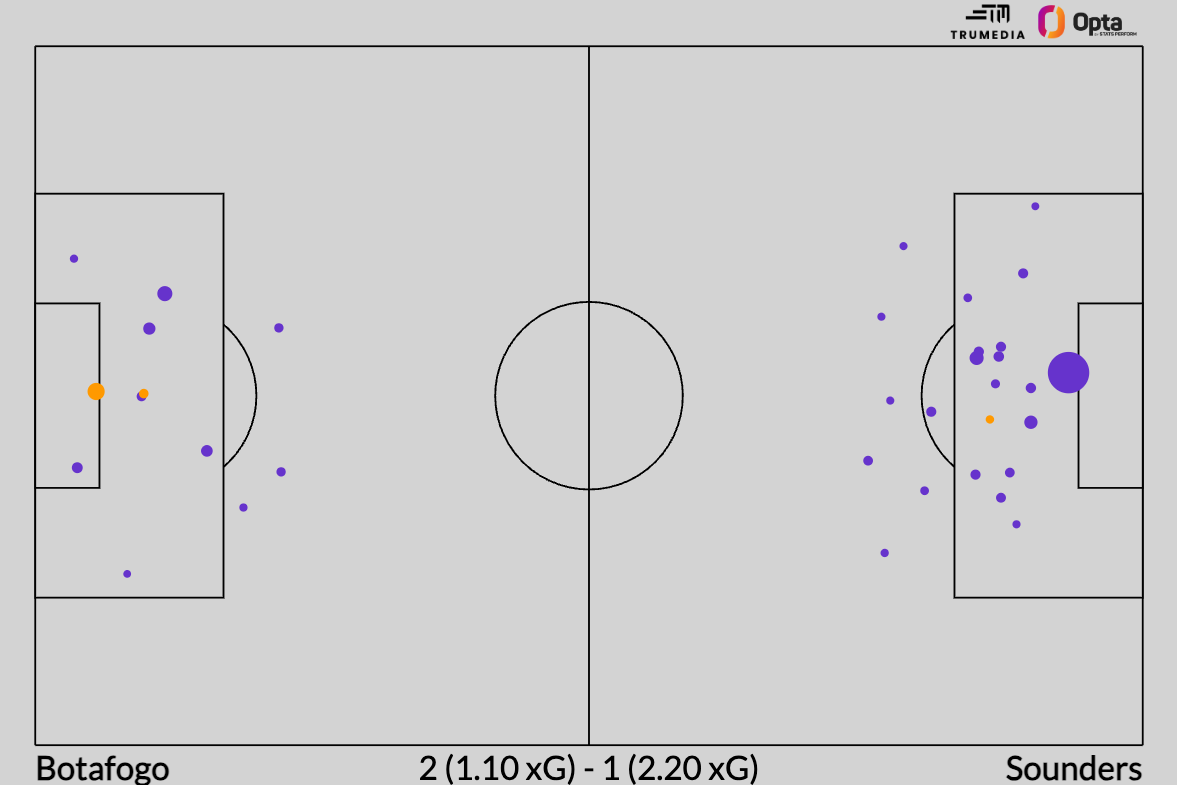

Take both of Botafogo's matches so far. They were outshot 23 to 12 by the Seattle Sounders in their opening game. And yet they won 2-1:

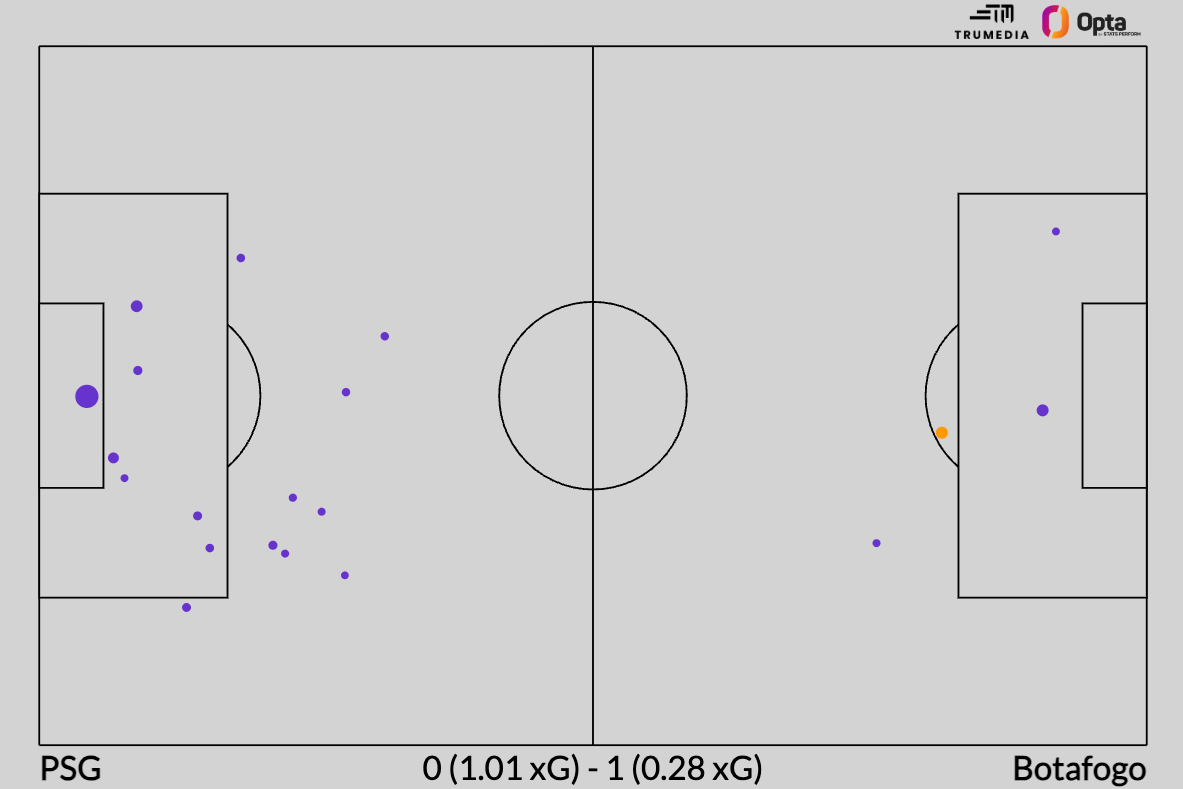

And then, they beat the presumptive best team in the world -- reigning UEFA Champions League winners Paris Saint-Germain -- in their second match despite creating barely any chances:

In modeling this out, do you reward Botafogo for a score-and-hold-on-for-dear-life victory against an MLS side? Do you actually reward the Sounders for creating better chances? Remember, we're not trying to hand out trophies based on these models; we're trying to use them to accurately predict the future. Now, a predictive stat like expected goals (xG) becomes a little less relevant as goalkeeper and finishing skill starts to diverge the further you go down the competitive ladder, but this wasn't a dominant victory like the scoreline suggests, either.

The vague state of play at this tournament, though, brings us to a more interesting juncture: This has to be a combination of art and science. Deciding how much these games should matter in modeling our understanding of the global landscape of the sport is not dissimilar to watching these games and trying to figure out how impressive any given individual performance actually is.

"Competitive matches between clubs from different confederations will create rare, high-value reference points that can calibrate both team and player strength across markets," Nazmiu said. "For example, if a midfielder from Asia outperforms their opposite number from a European team over 90 minutes, that's not definitive, but it becomes a meaningful data point when contextualized with performance trends from league and international play."

The same process applies to the teams as a whole: When Al Hilal tie a game with Real Madrid or Flamengo beat Chelsea, we shouldn't make sweeping conclusions about anything. The Saudi Pro League hasn't arrived, and Flamengo wouldn't necessarily qualify for the UEFA Champions League if they played in England. But at the same time, it would be just as silly to do the opposite: Ignore the results and act like they can't tell us anything, either.

We'll have to see how the results shake out as the Club World Cup stretches on and the biggest teams start to field stronger lineups and get serious about winning, but the first week of the tournament has at least opened up a possibility that not many people were really considering before the tournament began. That the gap between Europe and the rest of the world might not be quite as big as we previously thought.