If you don't shoot, you don't score. It's a basic mantra you probably heard from your under-8s coach.

Well, there are 139 players in the Premier League alone who shoot more than the center forward of Manchester United. That's right: One hundred one footballers who have played as many minutes or more as Rasmus Højlund, but have a higher shots-per-90 number.

Put differently, there are 187 outfield players who have played at least 1,200 minutes, like Højlund. More than half of them have taken more shots on goal than he has -- a list that includes defenders, holding midfielders and other players who don't spend much time at all in the opposing penalty area.

When it comes to understanding why Manchester United have trouble scoring goals -- only four teams have scored fewer than their 28 -- one reason could be that number: 1.20, the number of shots their center forward takes every 90 minutes.

If you don't shoot, you don't score.

Compare Højlund's 1.20 to his peers at other top clubs: Erling Haaland (3.82), Nicolas Jackson (3.24), Ollie Watkins (3.26), Alexander Isak (3.09), Luis Díaz (2.71), Darwin Núñez (2.60), Dominic Solanke (2.59). Heck, even the much-maligned Kai Havertz clocks in at 2.54.

Obviously goals (let alone shots) aren't the only metric to judge a center forward. But when you have a central striker -- especially in a 3-4-2-1 system -- who doesn't score much (he has two league goals) in part because he rarely shoots, it's worth diving into further. Because you're tempted to conclude that the issue is either Højlund or Ruben Amorim's system or some combination of the two.

Is it the system? Well, Amorim played the same system at Sporting CP, and his center forward there, Viktor Gyökeres, is averaging 4.59 shots per 90 minutes this season after notching 3.52 last season (and scoring 51 league goals since August 2023, which is more than four times as many as Højlund). Sometimes Amorim uses another center forward, Joshua Zirkzee. He isn't having the sort of season to write home about -- and has spent time in attacking midfield too, further away from goal -- but he still manages 1.96 per game, nearly twice as many as Højlund.

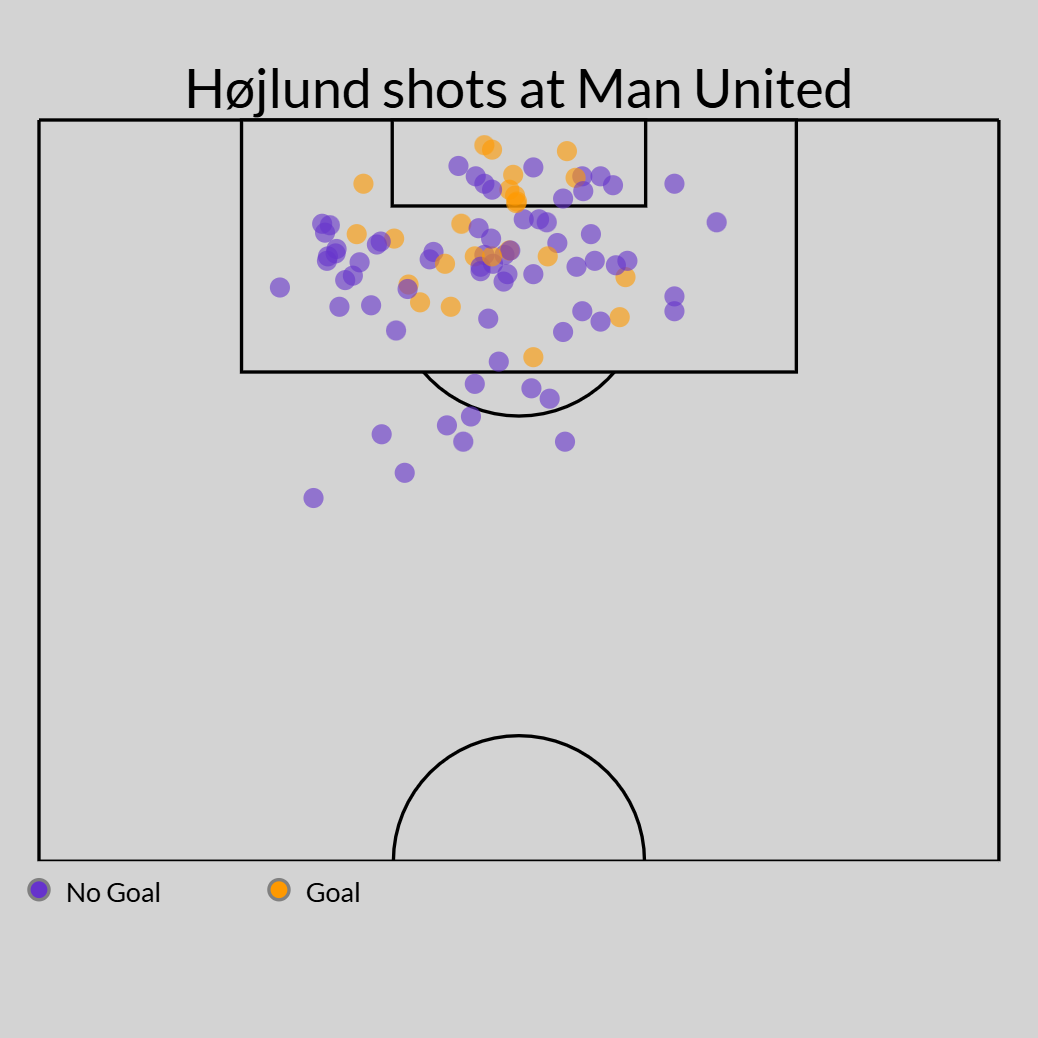

So is it Højlund? You're tempted to think so. He doesn't shoot much under Amorim and didn't shoot much under Erik ten Hag (it was marginally better at 1.40, but still very much subpar.) For that matter, he didn't shoot much in the season he spent at Sturm Graz in Austria, either, registering 2.10 shots per 90. The only time his number nosed above 2.5 is in the six months he was at Atalanta, when he reached 2.65, albeit on a far more attacking, high-tempo team.

If you don't shoot, you don't score.

Does this make Højlund the culprit of all the club's attacking woes? No. Obviously, there are other factors at play here. At United, he's alongside midfielder Bruno Fernandes, who averages 2.98 per 90, and that's bound to drive down his numbers. Not to mention, of course, that a center forward's job isn't just shooting on goal: Roberto Firmino didn't shoot much or score much for Liverpool, and he did rather well. Plus, Højlund just turned 22, and it's safe to assume he can improve with age.

That said, there's clearly a problem here. A central striker who shoots so infrequently either isn't getting himself into positions to shoot, lacks the confidence to shoot, or plays for a team that doesn't provide him the right kind of service to get into scoring situations. (Or, possibly, all of the above.)

It's up to Højlund to improve. It's up to Amorim to fix what United do in the final third. And if there is no uptick in his shots (and because they're correlated, his goals), it's up to the club to decide when to cut their losses and find somebody who will fire on goal at the right time.

If you don't shoot, you don't score.