It used to be pretty easy to predict the Premier League table before the season even started. You could just say "Manchester City, Liverpool, Arsenal, Chelsea, Manchester United and Tottenham -- in some order," and you'd usually be right.

In five seasons from 2009-10 through 2018-19, those six were the top six, and so they became known as the Big Six. In two other seasons, they all finished top seven, and in one other it was top eight. The only real outlier was the outlier, when Chelsea plummeted to 10th a year after winning the league and Leicester City won the whole thing. This was also the only season during this stretch when a club from outside the Big Six finished inside the top four.

As if in response to someone showing the world that the Premier League might actually be an open competition that anyone could win, the Big Six followed up 2015-16 by cordoning off the top six in three consecutive seasons. During those years, the average point gap between sixth and seventh was more than eight points. Over those three seasons, only four total non-Big Six teams finished a 38-game campaign with a positive goal differential.

What was happening? Per Deloitte's accounting, Arsenal brought in €445.2 million of revenue during the 2018-19 season. West Ham United, meanwhile, made €216.4m. Those were the sixth- and seventh-richest teams in the Premier League, and one earned more than twice as much money as the other. Revenue tends to be destiny in European soccer -- or at least it used to be.

Since 2018-19, the Big Six has finished as the top six only one time. An outsider has broken into the top four in each of the previous two seasons. And as of now, Nottingham Forest are tied with second-place Arsenal on points, Newcastle United are tied with fourth-place Manchester City on points and Bournemouth are only one point back of both of them. Oh, and Manchester United are 13th, and Tottenham are 15th.

So, is the "Big Six" officially dead? And if so, what killed it?

Theory No. 1: Everyone else in the Premier League got rich, too

You've read me write these words before, but the Premier League is, for all intents and purposes, the Super League.

For the 2022-23 season, per analysis by Kieran O'Connor of The Swiss Ramble, English clubs brought in a combined revenue of €7 billion. Next closest was the Bundesliga's €3.8 billion. And if you combined the revenues for LaLiga (€3.5 billion) and Serie A (€2.9 billion), those 40 clubs would've still brought in less money than the 20 Premier League sides.

Even with clubs massively cutting back on transfer spending over the summer, Premier League teams still spent more on transfer fees than Bundesliga (second-highest spend) and Serie A (third highest) -- combined.

Taking the summer and the current window together, Brighton have spent more on transfers than every other club in the world. And the net spend for just-promoted Ipswich Town, currently in 18th in the Premier League, is more than net spend of Bayern Munich, Real Madrid and Barcelona -- yes, combined. Or take Nottingham Forest, who signed multiple starting 11s worth of players over the past few seasons, gave the keys to a manager with Champions League experience and told him to just figure it out. And so far, he has!

With almost everyone in the Premier League spending at levels commensurate with Europe's super-clubs, then obviously the rest of the Premier League is going to improve. Seems pretty obvious, no?

Yes, and well, no. Wages tend to be the most powerful predictor of results, while transfer fees have only a tiny correlation with on-field success. And per data from the consultancy Twenty First Group, the ratio of wage spend from the Big Six to the rest of the Premier League hasn't really changed all that much.

In the 2013-14 season, the wage bill for the average Big Six side was 2.5 times the size of the average non-Big Six side. Last season, the ratio wasn't too different: 2.46 to 1.

Theory No. 2: Everyone else in the Premier League got smarter

This one pulls in multiple directions. First, it makes the bottom of the league less competitive.

Fewer promoted teams are really going for it: selling out -- er, rather buying out? -- and trying to revamp their Championship rosters into a team that can compete in the Premier League. Instead, promoted sides have begun to opt for younger signings who might stay at the club for a while and will retain transfer value but also might not be able to contribute right away.

Promoted clubs now know the risks of overspending on older players -- and the Premier League's Profit and Sustainability Regulations essentially force them to think longer term than they used to -- so they view promotion less as a last-chance for glory and more as a, say, short-term revenue infusion. With the parachute payments given to relegated sides, getting promoted, not overextended, raking in a ton of cash, getting sent down to the Championship, and then trying to repeat the process again makes a lot more financial sense.

This, then, leads to a situation where there are fewer competitive teams in the league. Last season, all three newly promoted sides were relegated, and all three this season are favorites to go down again. The Big Six was always expected to take tons of points from the six matches against the newly promoted teams. But now, so too are all of the other teams.

If you cut out the promoted teams and the Big Six, you're left with 11 clubs. Of those 11, two of them, Brentford and Brighton, are probably the two best-run clubs in England -- both owned by former professional sports bettors who run their clubs with a top-down mandate to make more objective decisions by using advanced data.

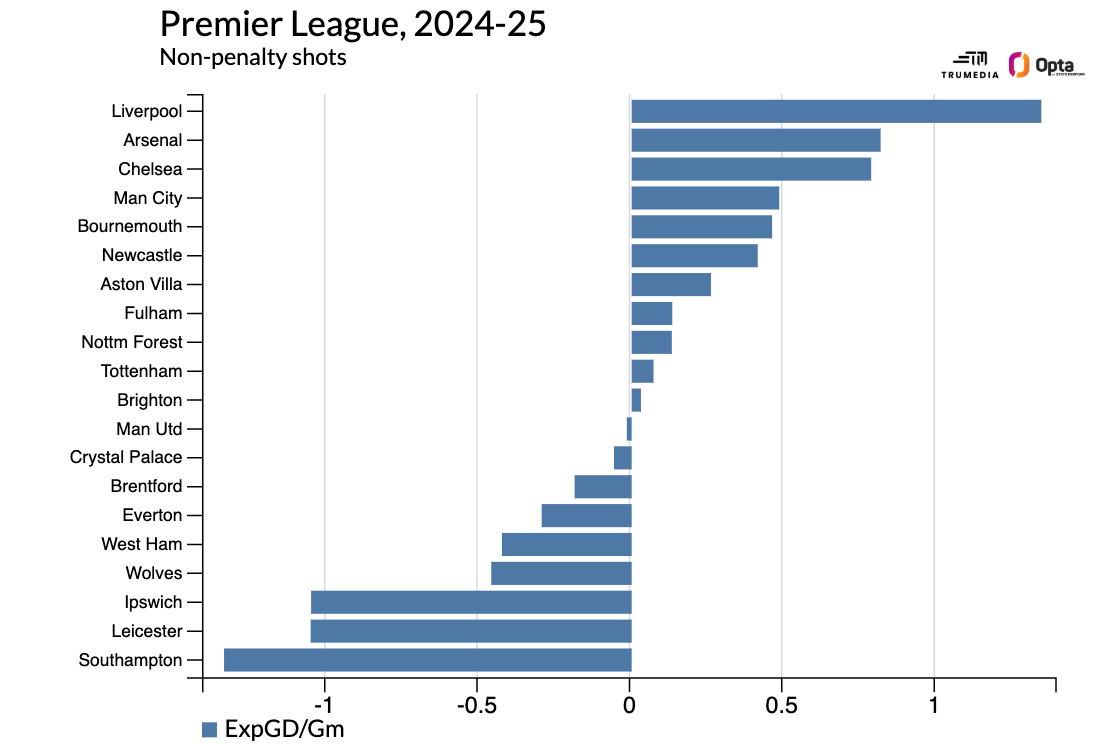

Bournemouth, too, have begun to lean in this direction under their new ownership. And according to some underlying data, they're currently one of the best teams in the league:

Crystal Palace seem like they've finally escaped the "retread British manager treadmill," and have become one of the most aggressive Premier League clubs at scouring the Championship for undervalued talent. As I wrote about in my book, "Net Gains," Fulham have always tried to use some kind of analytically informed decision-making process, albeit a frequently dysfunctional one.

This would all seem to be borne out in the results. Per Twenty First Group, the non-Big Six clubs were inefficient with their wage spend from 2013-14 through 2018-19. You can determine how many points the average team would be expected to win based on their payroll, and non-Big Six clubs were below that average. However, their inefficiency declined with each passing season, and since 2019-20, the non-Big Six clubs have been winning more points than expected based on their wage spend.

Except, all of that includes these noncompetitive promoted teams, plus the likes of Everton, West Ham, and Wolverhampton -- three poorly run clubs in very different ways. And while data is becoming a much bigger part of the game, it's still vastly overstated how much of an impact these numbers actually have on the way teams are run. And it's not like most of the big clubs aren't hiring some of the best analysts out there, too.

Theory No. 3: This is just a Manchester United story

There's only one real underperformer among the Big Six, and we all know who it is: Manchester United make as much money as any club, they pay wages that are competitive with every other club, they finished eighth last season and they're currently in 13th.

Rob Dawson reacts to Ruben Amorim's comments about his Man United team potentially being the worst in the club's history.

Man United were the only Big Six club who didn't finish in the top six last season, and when they finished sixth two seasons prior, they did so with a goal difference (zero) that ranked just eighth in the league. Even in their one successful season over the past three, they finished third despite producing only the sixth-best expected goal difference in the league.

Otherwise, this season, four of the Big Six are in the top six. Tottenham aren't there, but despite the growing number of calls for manager Ange Postecoglou to be sacked, they've been quite unlucky in a number of ways.

It seems like everyone for Spurs is injured -- some of which, sure, can be chalked up to Postecoglou's physical demands -- and they've also just distributed their goals in a very strange way. They've outscored their opponents by 10 goals this season, and yet they're in 15th. Only six teams have a better goal difference and 14 teams have more points. Without an injury crisis, Spurs comfortably finished fifth last season.

Theory No. 4: This is just a Newcastle United story

Obviously there isn't a Big Six anymore. There's a Big Seven.

Newcastle is now owned by Saudi Arabia's Public Investment Fund, which controls nearly a trillion dollars worth of assets. This makes Newcastle's owners the wealthiest owners in all of professional sports.

In their first full season under new ownership (2022-23), Newcastle finished fourth. Last season, they finished seventh -- but produced the fourth-best goal difference in the league. This year, they're in sixth place through 22 games.

During the heyday of the Big Six, there just wasn't another club like Newcastle in the Premier League -- or really, in all of professional sports.

Theory No. 5: It's everything, and it's all just random, man

Since 2018-19, a couple of larger shake-ups have hit the Big Six. Arsenal have tried to replace Arsene Wenger, who managed the club for 22 years. After a couple of seasons outside the top six, they've reestablished themselves as one of the best teams in the world under Mikel Arteta.

Because of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, former Chelsea owner Roman Abramovich -- under whom all of the club's modern successes occurred -- was forced to sell the club. The new owners, Todd Boehly and Clearlake Capital, have tried to reinvent the wheel with how they run the club, and while there were some initial struggles, they look like they're back to being one of the top six teams in the league.

And Tottenham ... well, Tottenham were always the least likely member of the Big Six. A Golden Generation of players, led by Harry Kane, perhaps the best center forward of the past decade, pushed the club into constant Champions League qualification. That added revenue, plus the construction of a new stadium, solidified their financial status as a top-six club, but now they're trying to build their first competitive team with an obvious superstar like Kane or Gareth Bale at the center of it.

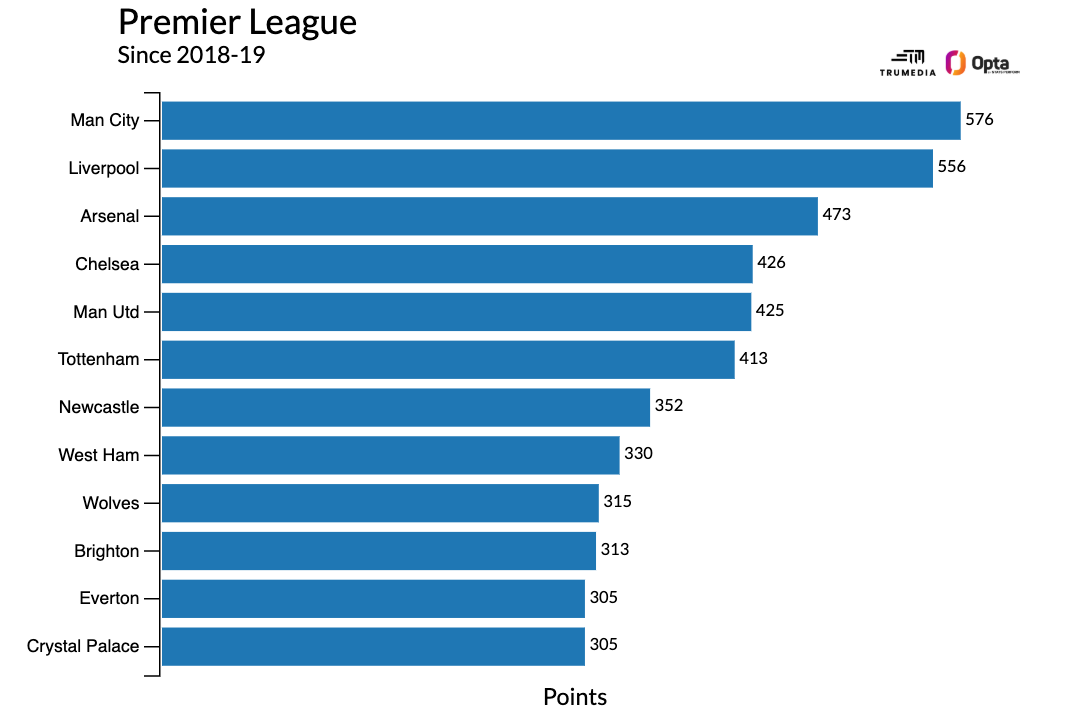

In other words, all three clubs have needed to spend some time rebuilding, and that has led to a few seasons in which each one fell out of the top six. Although these teams have all finished in the top six only once since 2018-19, they're still quite easily the six most successful Premier League teams since 2018-19:

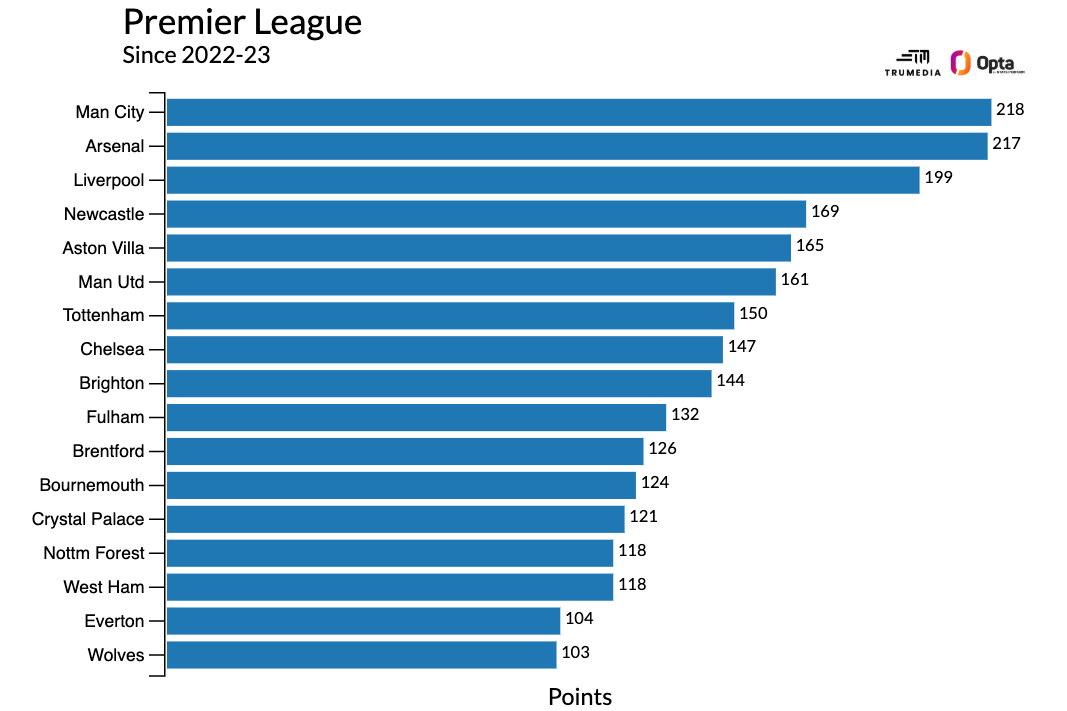

Zoom into the past three seasons, though, and it's not quite as obvious:

But that does a nice job of summing up the current landscape. Newcastle represent the rise of a seventh uber-rich club. Aston Villa, a club filled with players who would normally be playing for a top team in another country, coached by a guy who you could say the exact same thing about, represent the increased appeal of the salaries in the middle tier of the league. (While midtier Premier League teams aren't spending more relative to the Big Six, they are spending more relative to the rest of Europe.) And lastly, Brighton represent the increased willingness of not-as-rich clubs to try an alternative approach to winning soccer games.

It might not be long, if it hasn't happened already, until there's a new Big Six: one where Newcastle United replace Manchester United. But that Big Six will be different from the one we're used to.

The most likely individual outcome to any season will remain: the Big Six is the top six. But thanks to the rise in comparative spending power and a growing number of competent decision-making structures, it's more likely than not that, in a given season, one or two other teams get everything right -- enough transfers hit, enough starters develop at the same time, they find the ideal manager for their collection of talent -- and break the Big Six apart.