In 1998-99, Manchester United put together what many considered to be the greatest single season in the history of English soccer. First, they secured the Premier League title on the final day with a 2-1 comeback win against Tottenham. A week later, they took down the Premier League's greatest-ever goal-scorer, Alan Shearer, and Newcastle in the FA Cup final, winning 2-0. And then, finally and famously, they won the Champions League final against Bayern Munich, 2-1, with two goals in injury time.

Manchester United became the first English side to win the treble -- and they did it by averaging fewer points in the Premier League than Aston Villa are averaging this season under Unai Emery.

That's right. Through 13 games this year, Villa are averaging 2.15 points per match. Treble-winning Man United averaged 2.08. In fact, six other Premier League title-winners averaged fewer points per match than Villa's current rate. No team that's won points at or above Villa's current rate has ever finished below third place, and no team that's broken the two-points-per-game threshold has finished outside of the top four.

With the Saudi takeover of Newcastle, the Big Six comprising the league's top teams became the Big Seven -- and the door to the top four was supposed to be locked shut. Since Leicester City won the league in 2016 -- another team that averaged fewer points per game than this season's Villa -- no non-Big-Seven team has qualified for the Champions League. Thirteen games into this season, Villa, who haven't finished higher than seventh in over a decade, are way ahead of the pace.

How did Aston Villa do it, and is it a strategy other teams can copy? Also, how likely are Villa to keep it up?

The Aston Villa guide to crashing the Premier League top-four

If you zoom out far enough, European soccer becomes a two-track game.

The first track: finding ways to spend more money within the rules established by the Premier League and UEFA. That could be increasing sponsorship revenue, building more seats in your stadium, or simply getting purchased by a richer owner. On aggregate, spending more money will make your team better at winning soccer games.

People I've spoken to in European soccer say that new owners tend to drastically over-estimate the efficacy of track one. New owners think they can exploit advertising in under-served regions, invest in cryptocurrency, whatever -- but most of these revenue-boosting methods don't work to any significant degree because the biggest teams already eat up everyone's attention and the attendant commercial revenues. Outside of Chelsea's one cool trick to amortize contracts over an entire decade, the most effective way to increase your ability to spend is to qualify for European competition and secure Champions League television revenue.

The way you get to the Champions League brings us to the second track: being better at spending your money.

The two inputs for team performance, then, are total dollars spent and value (points or goals) per dollar. For the 2021-22 season, the gap between the fourth richest English team (Chelsea, €568.3 million) and the seventh-richest (West Ham, €301.5 million) was about €265 million. This isn't quite how it works, but it still makes the point, so just bear with me.

Over the past 10 years, the average fourth-place Premier League team has finished with 71 points. If the fourth-richest English team spends all of the money it makes, the efficiency of that spending needs to be €8 million per point for them to finish fourth. For the seventh-richest team, their efficiency of spending needs to be €4.2 million per point in order for them to hit the 71-point mark.

This is why the outsiders who have threatened to break into the top four are teams like Leicester and Brighton. The former acquired three different world-class players -- Jamie Vardy, N'Golo Kanté, and Riyad Mahrez -- for a little over €10 million combined. Brighton, meanwhile, are turning little-known prospects from lesser-scouted areas into stars, season after season. A team with, say, Manchester United's spending power and Brighton's spending efficiency would quite easily be the best soccer team in the world.

The non-Big-Seven Premier League teams, though, occupy a strange place in the soccer pyramid. They're mainly locked out of the Champions League, and they have way less money than the biggest teams in England. At the same time, they're all richer than almost everyone else in Europe. So, there's a whole class of players -- ones who'd typically play for, say, the third- or fourth-best teams in France or Spain or Germany or Italy, starters for mid-tier national teams and squad guys for the global powerhouses -- who are suddenly available to England's middle class of teams.

Villa are the perfect example of this. According to the estimates at FBref, they have the sixth-highest wage bill in the Premier League -- and the 11th-highest wage bill in Europe. Outside of England, only Real Madrid, Paris Saint-Germain, Bayern Munich, Barcelona, and Atletico Madrid spend more on player wages, per the FBref estimates. Again, these are estimates, but they show how Villa's strategy differs from the other recent top-four challengers. They're pretty much spending as much as they possibly can.

Per analysis by Kieron O'Connor in his newsletter the Swiss Ramble, Villa's squad cost -- player wages + transfer fees -- nearly doubled from 2021 to 2022. That gave them the eighth-most expensive squad in the league. But the club's spending has only continued since its latest financial numbers were reported.

Since then, they've signed France international winger Mousa Diaby for €55 million and Spain international center back Pau Torres for €33 million. And while there was no transfer fee attached to the arrival of Belgium international midfielder Youri Tielemans, he's the highest paid player on the team, per FBref. Diaby is on Big Seven-level wages; so is striker Ollie Watkins, who signed a new contract in early October.

Backed both by the powerful Premier League television revenues and by more owner investment than any other club in the league according to O'Connor, Villa have built a team that features the following players among its 11 most-used:

Argentina's starting goalkeeper (Emi Martinez)

England international center back (Ezri Konsa)

Spain international center back (Torres)

Poland international right back (Matty Cash)

France international left back (Lucas Digne)

Brazil international defensive midfielder (Douglas Luiz)

France international central midfielder (Boubacar Kamara)

Scotland international central midfielder (John McGinn

Italy international left winger (Nicolò Zaniolo)

France international right winger (Diaby)

England international center forward (Watkins)

Oh, and their coach? Unai Emery has managed Paris Saint-Germain and Arsenal, he's won the Europa League four times (three with Sevilla, one with Villarreal), and he took Villarreal to the Champions League semifinals less than two years ago.

Can Aston Villa hold on?

Although they're tied with Liverpool for third place in the league table, and just two points behind Arsenal in first, that doesn't quite reflect Villa's true level of performance this season.

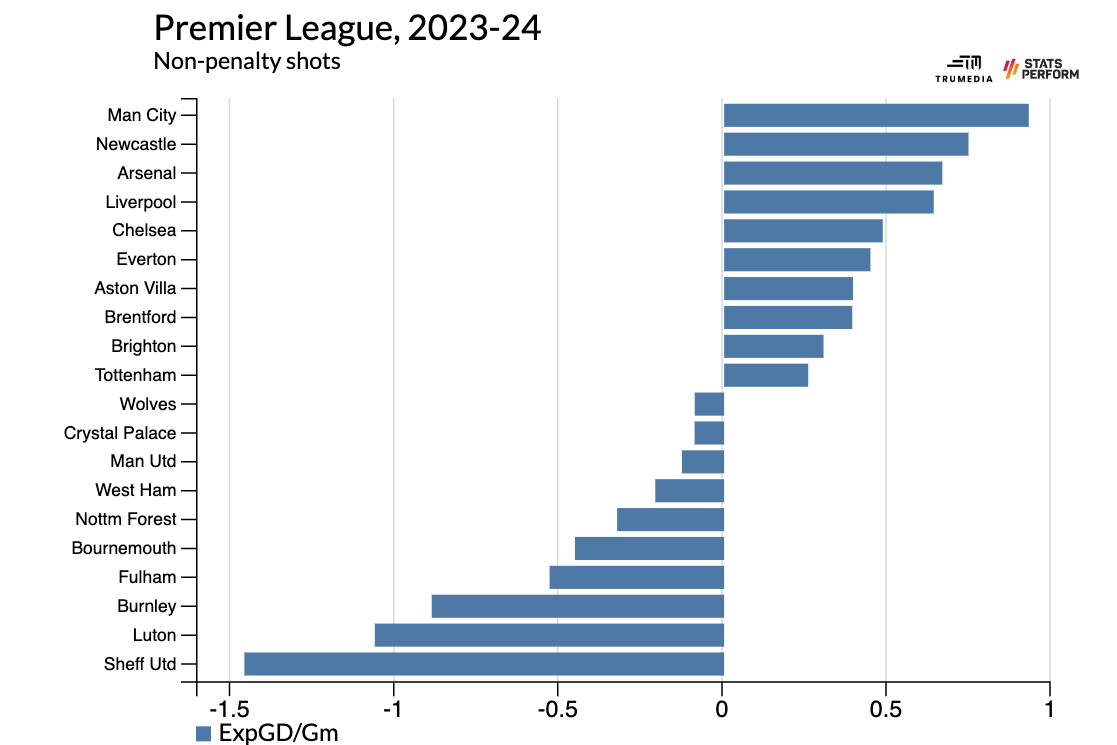

On the attacking end, they've scored 28 non-penalty goals. That's tied for second in the league. Compared to every team that's ever finished fourth in the Premier League, it'd be the second-best per game rate behind the 2017-18 Liverpool side that made the Champions League final. However, that total comes from 23.5 non-penalty expected goals, or xG. Although we should expect their attack to cool down, those underlying numbers are still third-best in the league behind Liverpool and Newcastle. This is one of the best attacking teams in the league.

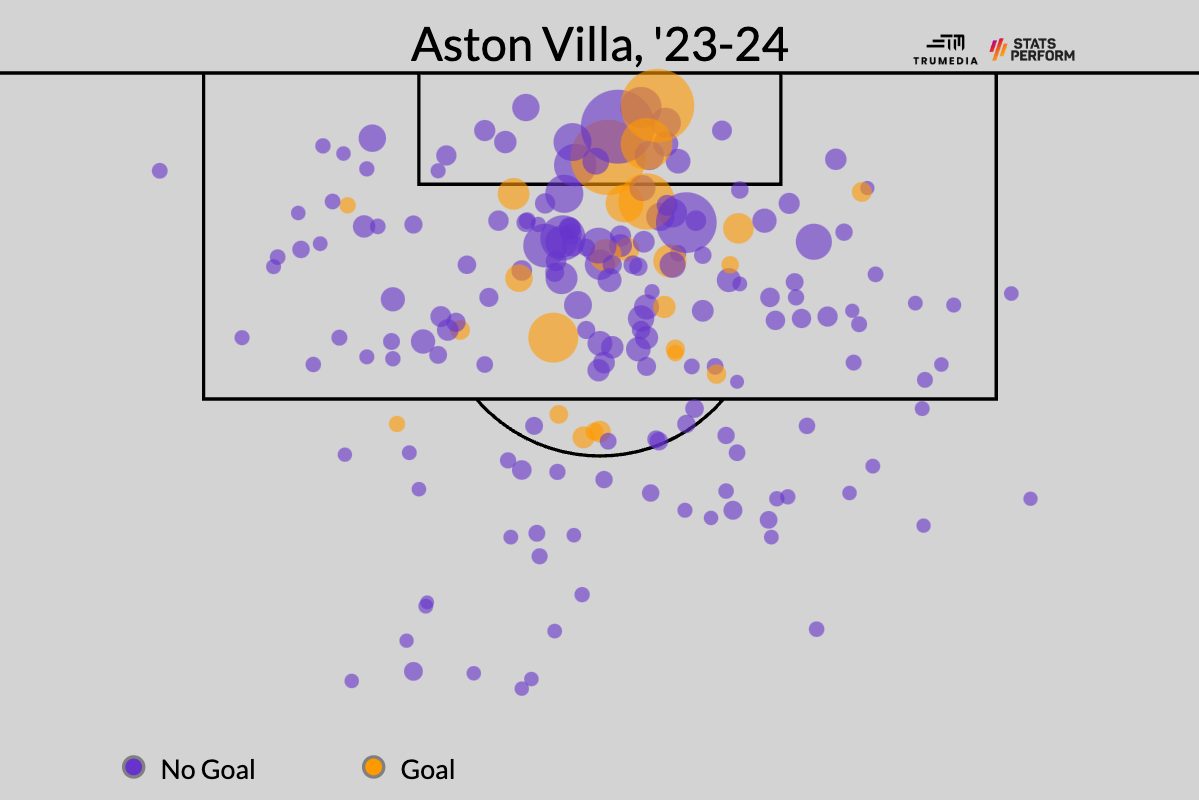

These are all of their shots, sized by the xG value of each attempt:

The main issue, then, is the defense, which has allowed 18 non-penalty goals from 18.4 xG -- just the 10th- and the 11th-best marks in the league. Emery has the team playing in a really strange way and frankly, it should not work.

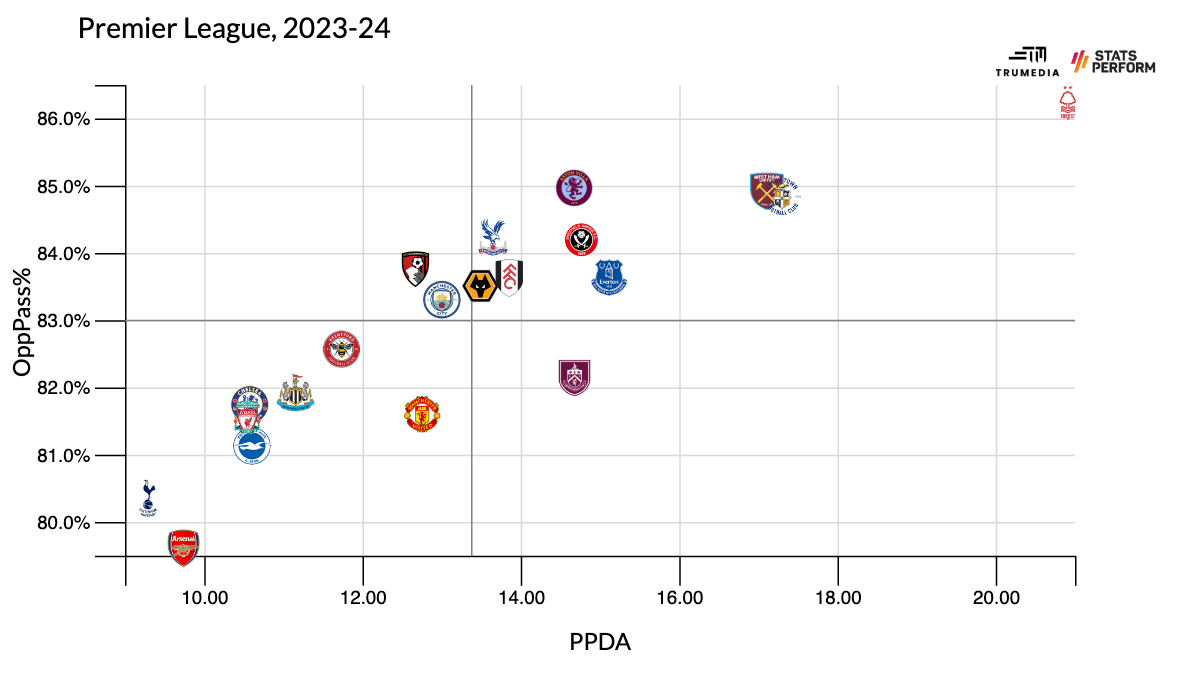

They're holding a very high defensive line, as evidenced by the fact that they've drawn opponents offside 63 times -- 20 more times than any other team in the league. Normally, you pair a high line with a high press so as not to give your opponents time to pick out runners behind your line. Villa, however, do not do that. Statistically, we can think of passes allowed per defensive action (PPDA) as representative of how much a team presses. And then we can think of opposition pass-completion percentage as representative of how effectively a team presses. Villa rank 14th in PPDA and 19th in opposition pass-completion percentage.

And so while Villa are only allowing the third-fewest shots in the league (10.8 per 90 minutes), they're also allowing the second-highest-quality shots in the league (0.132 xG per attempt) to their opponents. That's what happens when there's no pressure on the ball and tons of space for opposing attackers to run into. Villa keep a decent amount of possession (52.5%) and stay organized behind the ball in order to limit chances, but when they do give up shots, they tend to come from free runs in on goal.

All in all, the attack and the defense combine to generate the seventh-best non-penalty xG differential in the league:

By operating how Villa have, I think there's a cap on the quality of the team you can create. They're constantly spending a lot of money on already-established good players. Their average age, weighted by minutes played, is 27.2 -- slightly above league average. These players are unlikely to become superstars who could massively boost the team's performance level. For Villa, the way to find a superstar would-be through internal development (which is what happened with Jack Grealish) or making bets on younger, riskier players like Brighton do or Leicester did.

Villa's team-building approach is unlikely to produce a team that performs at an underlying level better than four of Manchester City, Manchester United, Liverpool, Arsenal, Tottenham, Chelsea, and Newcastle because they're essentially acquiring all of the players who those teams don't want.

However, this approach is also more likely to produce a team that performs at the level of its spending, which is essentially what Villa have been doing. And if you can be pretty sure that you're going to be the seventh- or eighth-best team in the league, you really just need a little bit of hot finishing or goalkeeping and a couple poor seasons from the richer clubs in order to bounce up into fourth. And that's exactly what's happened so far this year.

Villa have genuinely been a better team than both Tottenham and Manchester United this season. And thanks to some game-to-game volatility from both of the clubs, Newcastle sit five points back of Emery & Co., while Chelsea have a 12-point gap to make up. Throw in the, say, 75% likelihood that the Premier League gets a fifth spot in next year's Champions League, and Villa have a great shot at qualifying for next year's competition.

The biggest risk facing the club over the final 25 games is the lack of squad depth. The 10 most-used players have all played at least 85% of the minutes. While Torres and Martinez each missed one start, the other eight (Konsa, Cash, Digne, Luiz, Kamara, McGinn, Diaby, and Watkins) have all started every match. Newcastle were the least-rotated team in the league last season, with only five players who reached the 85-minute mark. What will happen to Villa's performance level once players outside of this 10-man core inevitably start to eat up a bigger chunk of the available minutes?

It's a tight path to walk, much like the club's broader strategy. Rather than attempting to build sustainable long-term success, Villa lost more money than any Premier League club from 2011 through 2021. They turned a small profit for the following season, but only because of the €117.5 million departure of Jack Grealish to Manchester City. Since Grealish came through the Villa system, his transfer fee gets booked as a pure, one-time profit, as opposed to the difference between his departure fee and the fee paid to acquire him. In the two seasons since, they've spent significantly more than they made in the transfer market, and they've boosted the overall wage bill.

That strategy got them here, to a point where they have enough talent to be sitting in the top four, with a ton of points through 13 matches. It might work -- they're projected to finish even on points with Newcastle in fourth by the Sporting Index betting-market right now -- and it might have to. When you spend this much money for a roster of prime-age players, you get a season or two where everyone is at their peak, but eventually, they all start to age. A number of your key players start to decline, and suddenly the team gets worse. The big wages that allowed you to bring them in suddenly prevents you from moving them on.

If Villa hang on for fourth or fifth, the revenue boost from the Champions League might allow them to break free from that cycle by allowing them to do even more of what they've been doing: spending. If not? It could be a long time until they're ever this high in the table again.