One of the things that makes soccer unique in the sports world is the main thing the failed Super League tried to change: the best teams and best players in the world rarely play against each other.

Of course, that's slowly -- or suddenly, depending on your frame of reference -- changing as the Premier League continues to gobble up the best players and best coaches, but just take the top 15 from UEFA's club coefficient rankings. You've got four teams from England (Manchester City, Chelsea, Liverpool and Manchester United), four from Spain (Real Madrid, Barcelona, Sevilla and Atletico Madrid), three from Italy (Juventus, Roma, and Inter Milan), two from Germany (Bayern Munich and Borussia Dortmund), one from France (Paris Saint-Germain), and one from the Netherlands (Ajax).

This creates a special kind of uncertainty. In other sports, we generally know how good each team is because they all play each other and the same opponents, all season long. In soccer, we can only sort of tell how Manchester City compare to Real Madrid until they play each other ... and then City win 5-1 on aggregate.

It goes in the other direction, too: The best team in the Premier League should wipe the floor with the third-place team in Serie A ... and then Inter Milan hang tough for 90 minutes and outshoot City 14-7 in the Champions League final.

Now, take that team-to-team uncertainty, multiply it by 1,000 and you've got the player-to-player uncertainty. Is it harder to be a center back for Bayern Munich, or Manchester United? Is the best winger on Atletico Madrid equal to Borussia Dortmund's star wide-man? And how the hell do we even begin to contextualize what it means to perform for PSG?

Put another way, we don't really know what it means to be "world class." Everyone says it, using it as shorthand for, uh, well, something -- something like "quite good" or "one of the best." But despite all of the uncertainty about how teams and players compare, let's try to define the phrase -- and then figure out who deserves the tag.

What is 'world class'?

The phrase itself is defined, across various dictionaries, as "one of the best there are in the world," or "among the best in the world" or "as good as best in the world". Based on the going definitions, "world class" is being used properly, then. By just tossing the phrase around without any real rigor, we're honoring its meaning.

And its meaning is, well, meaningless. "Among the best in the world" could describe every professional soccer player in Europe. Per NCAA data, around 1% of American high school soccer players go on to play Division I soccer. Does that make me world class?

Of course not, so let's try to do better.

You don't really hear "world class" being used to describe other sports. For anything that peaks in importance in the Olympics, the idea is sort of implied. You win the gold medal and you're the best in the world. Silver, you're second-best, and on and on. In a less global game like American football, it's assumed that all of the best players in the NFL are the best players in the world. The same is true of in the NBA, a league mostly made up of Americans, but increasingly dominated by athletes from outside of the 50 states.

In football and basketball, players get awarded with All-NBA and All-Pro designations at the end of the season. In the NBA, five players get it. In the NFL, it goes to 22 -- 11 on offense, 11 on defense -- plus a handful of special teams players. These are, essentially, the world-class players in these sports, and they're limited to the number of players that are on the field in a given moment, and further reduced to the generalized positions these players play. As the sport has moved toward positional fluidity, the NBA is considering removing positions altogether and just selecting five players.

Both sports also have a second team, while the NBA has a third-team, too. So, across any given season, there are either two or three teams worth of world-class players.

If we take a combo of the NFL and the NBA's format and apply it to soccer, then it gives us this: at any given moment, there are 22 world-class soccer players. It breaks down to two keepers, four fullbacks, four center-backs, two defensive midfielders, four central midfielders and six forwards. That's it.

So who is world class?

I want to try to do this objectively, but that's just not possible. While data can do a decent-ish job of identifying all of the good or great players, the numbers we have still aren't precise or contextualized enough to provide any kind of ranked certainty. (They never will be, but that's another column.) So, rather than base this off of some kind of combo of numbers plus the so-called eye test plus my own subjective intuition, I'm going to do something slightly different.

Each month -- as I've written about before -- a group of journalists across Europe pick a best XI known as the European Sports Media Team of the Month. It's not perfect -- and as these things usually do, it leans heavily on players from successful teams -- but it's kind of a nice little hybrid of expertise and crowd-sourcing that's not biased toward any particular country.

So far, we only have nine months' worth of voting for this season. We're still waiting for May, which, historically, is heavily tilted toward the teams -- in particular the winner -- of the Champions League final. That's not a ton of data, and a player with three amazing months and six terrible ones would grade out better than a guy who was good all year but only made two teams of the month.

So, we're also going to look at last season for a bit more information, but we'll only weigh those Team of the Month appearances as half as valuable. Then we'll add them up, throw in just a couple of subjective adjustments, and get our first set of world-class players.

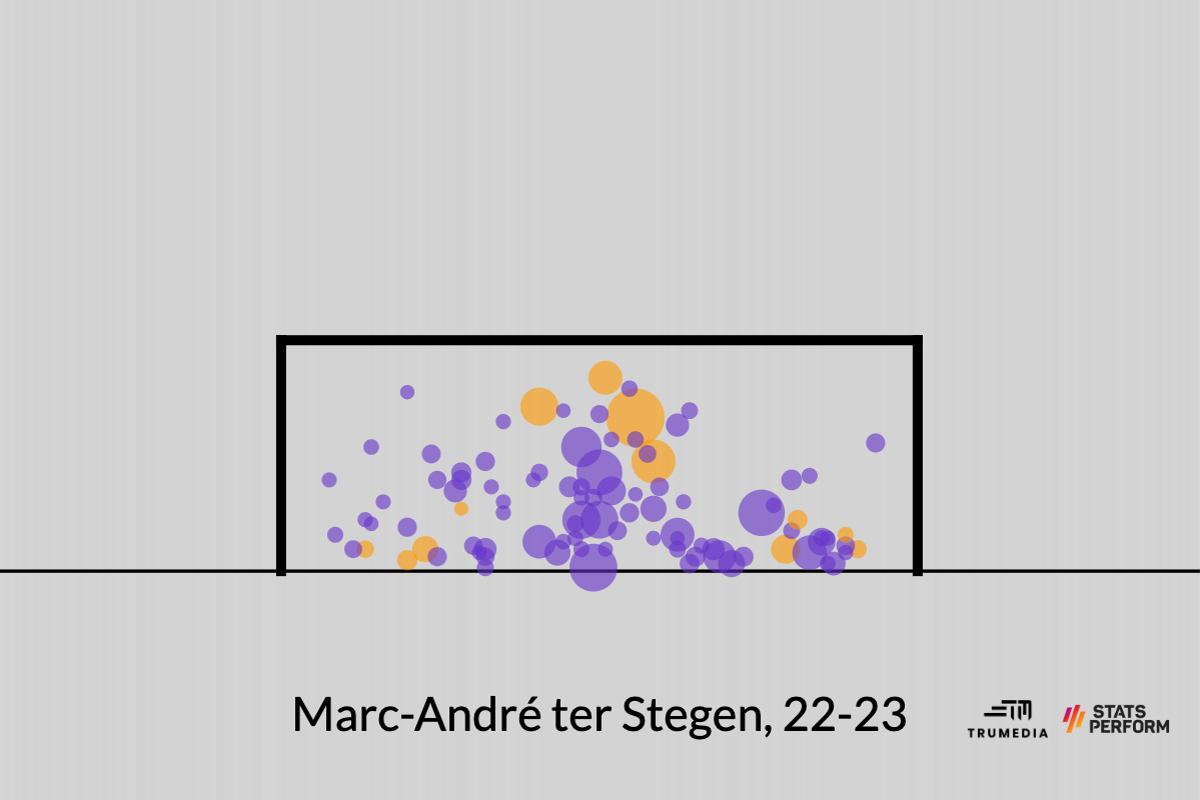

Starting in goal, the first-team nod goes to Real Madrid's Thibaut Courtois, who not only led all keepers in votes this year (three) and last year (six), but leads all keepers in team of the month appearances since 1995 with 19. Behind Courtois is Barcelona's Marc-Andre ter Stegen (two points), who conceded the fewest goals of any starting keeper in Europe this season and, per Stats Perform, saved 8.7 goals more than expected this season.

(Purple are saves, orange are goals, circles are sized by the probability of a goal being scored from the shot:)

On the whole, I think ter Stegen was better than Courtois this season -- and I think Liverpool's Alisson, who saved 10.1 goals more than expected (best in Europe), was probably better than both of them. But Courtois does seem to have a knack for big saves in big moments, and ter Stegen's saves -- in a La Liga title race -- ended up being a lot more valuable than Alisson's were this season.

These are the three best keepers in the world, but we can only say two are world class. Now, to the fullbacks, where there's one clear standout, and it's ... Joao Cancelo?

The Man City defender made eight of nine teams of the month last year, and he made the first three teams this season, too. In fact, only two other players -- at any position -- have accrued more points since the start of last season than Cancelo's seven. Of course, he was first benched by Manchester City and then sent out on loan to Bayern Munich, where he bounced in and out of the lineup for maybe the worst Bayern team in a decade.

City also, you know, went on an absolute tear -- and won the treble -- after Cancelo went out on loan, so we're disqualifying him from consideration. By our definition, world-class players simply don't get benched and sent away in the middle of the season.

With no Cancelo, the first-team fullbacks are then AC Milan's Theo Hernandez (4.5 points) and Liverpool's Trent Alexander-Arnold (four points). The former is one of the best ball-carriers in the world from the fullback position, while the latter is one of the best passers in the world, full stop.

On the second team, we've got Napoli's Giovanni Di Lorenzo (2 points) filling one slot. He played almost every minute for title-winning Napoli this season and was the team's most valuable player per Edvin Hoac's Estimated Impact metric, which tries to combine on-off team-performance stats with individual player statistics.

The other slot requires me to step in and make an editorial decision. Both Real Madrid's Dani Carvajal and PSG's Achraf Hakimi are tied with 1.5 points, but neither one feels quite right. And neither does what I'm about to do, which is: give the spot to Real Madrid's David Alaba, who has two points.

The Austrian super-utility defender only started 11 games at left back this season, per the site FBref, but I think we need at least one representative of that new kinda-fullback-kinda-center-back role that's taking over backlines across Europe. Alaba hasn't played it, per se, but he'd do it better than anyone out there.

At center-back, Napoli's Kim Min-jae leads the way with four points -- all accrued this year in his first season in a Big Five league after arriving from Fenerbahce last summer. Two years ago around this time, he was playing for Beijing Guoan; now he's a world-class center-back.

His partner on the first team -- for now -- is Real Madrid's Eder Militao with three points. I say "for now" because Manchester City's Ruben Dias is a lock to get another vote for May, which would bring him even with Militao. And given how the seasons went -- Real Madrid didn't win LaLiga or the Champions League; Manchester City won everything and thumped Madrid along the way -- I'd give Dias the first-team nod.

For now, though, he's on the second team with Liverpool's Virgil van Dijk, who didn't earn any points this year, but accrued four votes (two points) last season. He hangs onto world-class status -- again -- for now. No one else stood out for long enough to take it from VVD.

In the midfield, I had to decide to just go with any old midfielders or to divvy it up by roles. I think defensive midfield is a categorically different position from the more advanced midfield roles, so we're going to chop it up.

The first-team defensive midfielder is Manchester United's Casemiro, who earned two points this season and then half a point last year. After him, there are only four theoretically "holding midfielders" with a full point. (The first three: Liverpool's Thiago, Chelsea's Enzo Fernandez, and Fiorentina's Sofyan Amrabat. Thiago is barely a holding midfielder and barely played soccer this year, while the other two earned their votes mainly because of World Cup performances.)

So, instead, it goes to Manchester City's Rodri, who for my money is the best defensive midfielder in the world. He'll get another vote in May, which will bump him above the other three. He scored the winning goal in the Champions League final, and Estimated Impact rates him as ... the most valuable player in the world.

("Estimated impact" is defined as "a player's impact on their team's goal difference per 90 minutes, compared to the average player" in the Premier League.)

Now for the advanced midfield roles, which are led by Manchester City's Kevin De Bruyne, who leads all players with eight points. Like his countryman Courtois, he also leads all midfielders in TOTW appearances since 1995 with 30; Xavi is second with 24 and Zinedine Zidane is third with 23. Pretty good, huh?

Joining him on the first team is Real Madrid's Luka Modric (4.5 points). This feels like a bit of a legacy vote -- he's 37 and only started 19 league games this season -- but he was also lights-out at the World Cup, and it's his spot until someone else comes and takes it. Some potential usurpers: the two second-team midfielders, Barcelona's Pedri (three points) and Arsenal's Martin Odegaard (three points).

Lastly, the forwards. In the NBA, there's been an issue with the center position. Denver's Nikola Jokic and Philadelphia's Joel Embiid have finished first and second in MVP voting in each of the past three seasons. But since the All-NBA ballot only has one center slot, the second-best player in the world continues to be left off the team that's supposed to represent the five best players in the world.

To avoid that problem here, we're not worrying about positions or footed-ness or whatever. Forwards are the most valuable players in the sport, and we're making room for the three best and three second-best regardless of how they might fit together in real life.

Leading the way up top is Manchester City's Erling Haaland, with approximately 900 goals and 7.5 points. He's joined by his former Bundesliga rival, Robert Lewandowski, who led La Liga in goals and led Barcelona to their first league title in four years in his first season in Spain. And then there's Real Madrid's Vinicius Junior, who I think is the most consistent attacker in the world. Some of these other players can disappear for matches at a time, but I haven't seen a single Madrid game over the past two seasons in which Vini didn't impact the outcome in some way.

It's not Haaland vs Mbappe; it's Haaland vs Mbappe vs Vini.

Kylian Mbappe, of course, comes in on the second team. He would also be joined by Karim Benzema and Lionel Messi (four points each) -- imagine that front three! -- but with Benzema cashing out in Saudi Arabia and Messi moving on to Inter Miami, they sacrifice their world-class designations by giving up "Big Five" soccer, as far as I'm concerned. So in slides the (for now) Napoli duo of Victor Osimhen and Khvicha Kvaratskhelia.

Is it a perfect list? Not quite. (Jude Bellingham, anyone?) But I think it's a pretty good encapsulation of who would be considered world-class if we figured out what we actually meant when we said it.

The specific definition I settled on here reveals something larger, too: There are tons of great players who aren't quite world class. After all, if you want to add any names onto this list, you still have to take some others out.

Our World Class First-Team selections

GK: Thibaut Courtois (Real Madrid)

DF: Trent Alexander-Arnold (Liverpool), Kim Min-Jae (Napoli), Eder Militao (Real Madrid), Theo Hernandez (AC Milan)

MF: Casemiro (Man United), Kevin de Bruyne (Man City), Luka Modric (Real Madrid)

FW: Erling Haaland (Man City), Robert Lewandowski (Barcelona), Vinicius Jr. (Real Madrid)

Our World Class Second-Team selections

GK: Marc-Andre ter Stegen (Barcelona)

DF: Giovanni Di Lorenzo (Napoli), Ruben Dias (Man City), Virgil van Dijk (Liverpool), David Alaba (Real Madrid)

MF: Rodri (Man City), Martin Odegaard (Arsenal), Pedri (Barcelona)

FW: Kylian Mbappe (PSG), Victor Osimhen (Napoli), Khvicha Kvaratskhelia (Napoli)