AUGUSTA, Ga. -- Head down and hands in his pockets, looking like he had just seen a ghost, Jordan Spieth trudged from the Augusta National cabins toward the wide circle of men, women and children surrounding the site of Danny Willett's championship ceremony. Spieth was wearing a green jacket, and trust me on this: You have never seen someone look so unhappy wearing a green jacket on a Masters Sunday.

This is always a difficult exercise for a reigning champ who had failed to defend his title, this ritual that starts with a Butler Cabin passing of the jacket to the new winner on CBS, and then more of the same for the fans and cameramen waiting near the putting green. But there never has been a more brutal exchange than this Spieth-Willett handoff, and there might never be again.

Billy Payne, club chairman, expressed his undying gratitude to Spieth for being "such a splendid champion this year." Soon enough, Spieth was conducting a group interview near the clubhouse, and conducting himself like the old pro and old soul this 22-year-old has always been while explaining the inexplicable at the 12th hole.

A club elder and the player's agent, Jay Danzi, ultimately escorted Spieth to the champions' parking lot in front of the clubhouse; the player actually nodded toward a few reporters he passed along the way. Nick Faldo stopped him at the passenger side of his waiting courtesy car to shake his hand and offer a word of reassurance. Twenty years ago, Faldo was the beneficiary of Greg Norman's epic meltdown, and just before he ran into Spieth, the three-time Masters winner agreed that this collapse made Norman's feel like a joyful stroll down Magnolia Lane. "Greg was right from the word go on a downward trend, and Jordan was on an upward trend," Faldo told a small group of reporters. He called this Shakespearean tragedy on the back nine "a mixture between disaster and torture."

Still reeling, Spieth slid into a gray Mercedes SUV and was driven out of Augusta National at 8:01 p.m. ET. Standing near the clubhouse was the Masters rookie he'd spent the day with, a kid named Smylie Kaufman, who had just shot 81 and was assuring someone standing near him, "There definitely will be a next time. The sun will come up tomorrow."

Yes, it will rise in the morning whether Jordan Spieth wants it to or not.

"It just kind of stunk to watch it," Kaufman said about the second-place finisher who had just shot 73.

Nothing on this golf course, or any golf course, has been harder on the eyes in the history of the sport than Spieth's quadruple-bogey seven at the 12th. Norman had started bleeding away his 6-stroke lead before the turn, and he was playing with a terminator, Faldo. Norman was already known to grip the club too tightly when the stakes were high.

Arnold Palmer blew a 7-shot lead with nine holes to play at the 1966 U.S. Open, but he was forever known as a go-for-broke gambler. He foolishly (but predictably) chased Ben Hogan's scoring record, and he was playing with an opportunistic Hall of Famer, Billy Casper. Jean van de Velde got wet and wild with the 72nd-hole lead at Carnoustie in 1999, but he was hardly a great player and that was more comedy than tragedy. There was nothing remotely funny about this one. This was Phil Mickelson's 72nd-hole wipeout at Winged Foot times 10, if only because Mickelson was always as reckless and as entertaining as Arnie in the choices he made.

"I can't imagine that was fun for everyone to experience," Spieth said, "other than Danny's team. And those who are fans of him."

Willett, a 28-year-old Englishman, is a talented player and deserving champ, not to mention the proud father of a newborn son; his wife's pregnancy nearly kept him out of the Masters. He was the last man in the field and the last man standing, earning his breakthrough victory with a 67 on his wife's birthday.

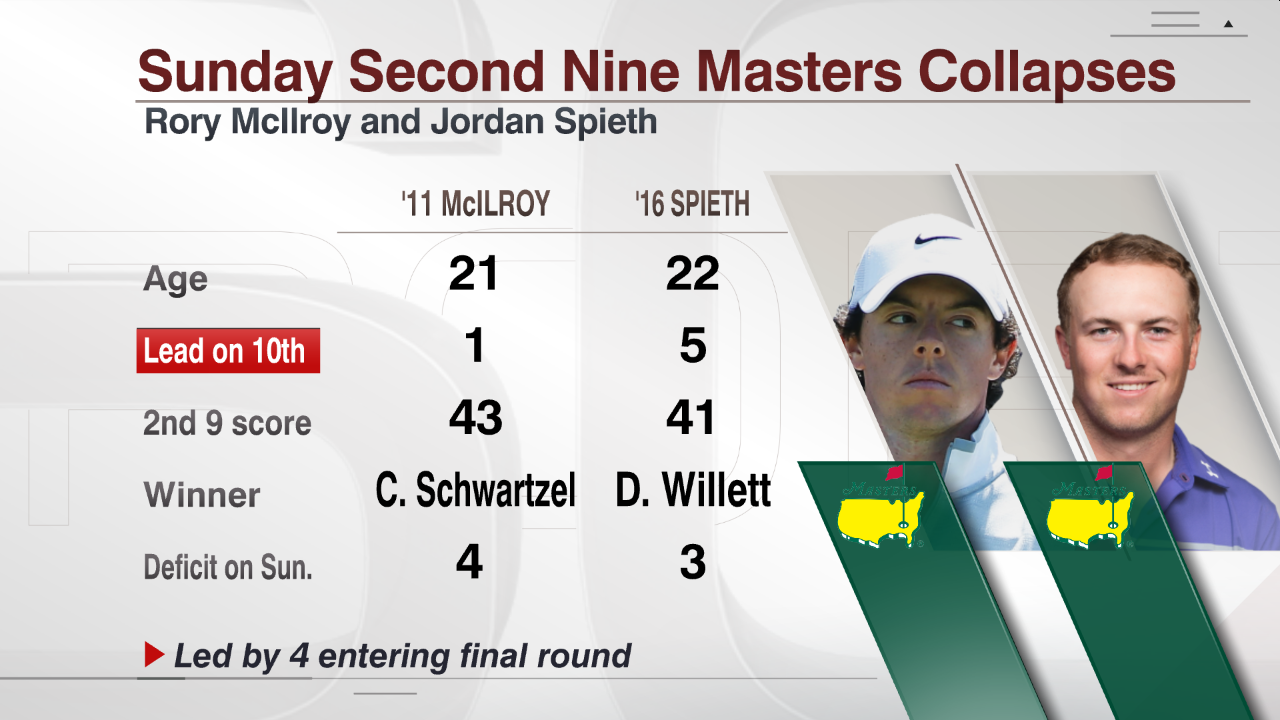

But this was Jordan Spieth's Masters to lose, and lose it he did in a staggering way. He closed out the front nine with four straight birdies to wipe out Kaufman and, it appeared, the rest of the field. "A dream-come-true front nine," Spieth called it. And this is what awaited him as he stood on the 10th tee with a 5-shot lead and the whole world expecting that the back nine would amount to a tap-in putt for the leader:

Spieth was going to become the youngest player in the Masters era to have claimed three majors. He was going to become the game's first back-to-back, wire-to-wire major winner. He was going to win a second Masters in his third appearance after it took Tiger Woods seven appearances to win his second, and after it took Jack Nicklaus and Palmer six appearances to win their second.

At 22, Spieth was going to match the number of green jackets won by Ben Hogan, Byron Nelson, Seve Ballesteros and Tom Watson. He was going to join Woods, Nicklaus and Faldo as the only players to win two consecutive Masters, and he was going to become the first Masters champion since World War II to have overcome at least three double-bogeys.

You know what people would've said about Jordan Spieth if he did all that, don't you? They would've said Spieth could someday surpass Nicklaus' six Masters titles and become the greatest Augusta National player of all time.

Instead, they will talk about a different kind of history that started taking shape on the 10th and 11th holes, when Spieth began playing prevent defense and lost his aggression and focus. He could've survived his bogeys on those holes; everyone knew that. Just as everyone knew he couldn't survive his self-destructive decisions at the famously evil 12th.

He had a 9-iron in his hands and a 150-yard tee shot to execute. Spieth and his caddie, Michael Greller, agreed that a draw was the right call, but when the defending champ stood over the ball, he started listening to a devilish voice in his head telling him to hit a cut. "And that's what I did in 2014," Spieth said, "and it cost me the tournament then, too."

The ball landed short and bounced into Rae's Creek, but guess what? That shot didn't cost him the tournament, and for what it's worth, Spieth is a far more experienced player than the 2014 rookie he was on Bubba Watson's watch. Just like Mickelson's second swing on the final hole at Winged Foot proved far more costly than his first, Spieth blew it on his second swing, too, after taking a drop 80 yards from the pin.

"I'm not really sure what happened on the next shot," Spieth said.

Millions of flabbergasted viewers knew exactly what went down. Spieth choked, and sometimes it happens to the best of 'em. It's a tough thing to say about perhaps the world's toughest player, but there's no better way to describe this 25-handicapper hack. His divot was the size of a three-car garage, and it nearly traveled as far as the ball that barely reached the water.

The unbreakable Spieth was broken. He put his next shot into the bunker, made 7 and arrived at the 13th tee 3 strokes behind Willett. "Buddy," Spieth told his caddie, "it seems like we're collapsing."

What he did to the 12th hole on Sunday was more shocking than what Ernie Els did to the first hole on Thursday, and Faldo estimated that Spieth went from commanding leader to zombie film victim in 12 minutes that no witness will ever forget.

Let's face it: There's losing the way the Seattle Seahawks lost to the New England Patriots on the Super Bowl goal line, and then there's losing like this. I've been writing about sports for 30 years, and this is the most shocking event I've ever covered, with the 2004 American League Championship Series between the New York Yankees and supposedly haunted Boston Red Sox running a close second.

"This is going to hurt badly," said Faldo, who comforted Norman 20 years before doing a little of the same for Spieth. "He was on the steps of doing something to join our little club, which would've been great. I would've welcomed him to our little club of those who have defended. The good news is he's 22. You regroup. He's way too talented. ... He's got a lot of majors he's going to have a shot to win."

Norman never won a Masters, and Palmer didn't win any majors after the U.S. Open at Olympic in '66. Spieth is too young and too resilient to suffer the same fate, and his birdies on 13 and 15 and near-bird on 16 explain why. The kid's a winner; that hasn't changed. Spieth surprised nobody when he got a bit choked up thanking those who cheered his rally. "And they almost brought me back into it," he said.

Almost. Out of left field, the 80th Masters turned into the craziest, and Spieth was left to wear a look of torment as he headed up the 72nd fairway with his hat off, rubbing his head. Suddenly the boy wonder looked every bit as old as his receding hairline suggested.

He'd shot that opening 66 with his new driver Thursday and pulled off that wild shot from the trees on 11, and everyone figured it was all over then. "Jordan's on a mission," his father told ESPN.com after that round. "He's not talking a lot."

He was quietly, but forcefully, playing angry to prove to everyone he was still the same guy who nearly won last year's Grand Slam. But the only player ever to reach 19-under at Augusta National (in 2015, before finishing with a share of Woods' record at 18-under) was instead given the cruelest lesson about the cruelest game on earth.

Golf defeated Spieth because golf eventually defeated everyone. And when this Masters was finally in the books, Spieth still had to put a green jacket on another man's shoulders.

"As you can imagine," he said, "I can't think of anybody else who may have had a tougher ceremony to experience."

The only thing tougher than the ceremony was the pain suffered before it. Jordan Spieth might someday own four, five, six Masters titles. But even at the age of 22, this much is true about his 2016 Augusta National Sunday: He will take it to his grave.