Page 2

Editor's note: This article appears in the Jan. 29 issue of ESPN The Magazine.

Any late-night-cable junkie has stumbled across a movie about Steve Prefontaine and felt either excited (because it's the one with Billy Crudup) or bummed out (because it's the one with Jared Leto). I'd say this has happened to me 20 times over the past few years. If I see Crudup or Jack Bauer's dad, I'm in. If I see the blonde from "Melrose Place" or Leto wearing one of those awful wigs, I'm out. But either way, I always ask myself the same question: Why did Hollywood feel the need to release competing biopics about a long-distance runner who finished fourth in the 1972 Olympics? One would have been plenty, right?

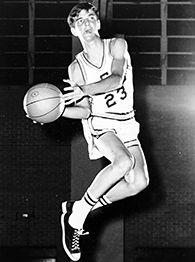

The book world has just produced a similar head-scratcher: two competing biographies of Pete Maravich, one by acclaimed author Mark Kriegel, the other by Wayne Federman and Marshall Terrill, who spent five years putting their book together in collaboration with Pete's widow, Jackie. On the surface, dueling Maravich books seems even stranger than dueling Prefontaine movies. After all, Pistol Pete died 19 years ago, didn't win anything other than some scoring titles and never played in the Final Four -- or past the second round of the NBA playoffs. His 10-year pro career spanned the depressing '70s, a decade marred by drug and alcohol abuse, overpaid head cases, tape-delayed playoff games, violent fights and sagging attendance. We always hear that Bird and Magic saved the NBA. Doesn't that mean they saved it from people like Pete Maravich?

Of course, I plowed through both Maravich books in a week. When my family owned Celtics season tickets in the 1970s, I cared about seeing only five visiting players: David Thompson, Bill Walton, George Gervin, Julius Erving and Pistol Pete. Maravich was like 12 Globetrotters rolled into one. No pass was too far-fetched, no shot too far away. He'd glide across the court -- all rubbery limbs, ball attached to his hand like a yo-yo, blank expression on his face -- and nobody knew what would happen next. The scoreboard never seemed to matter as much as the show. Kids from that era remember his appearances on CBS's halftime H-O-R-S-E contests more fondly than any of his games. Even his basketball cards were cool, like the one from 1975, when he sported an extended goatee and looked like a count.

So you can imagine my delight when Red Auerbach plucked an end-of-the-line Pistol off waivers during Larry Bird's rookie season. We picked up The Pistol for nothing? Sadly, he was woefully gaunt and out of shape. Limping around on a bum knee and wearing a gawd-awful perm that made him look like Arnold Horshack, The Pistol struggled to blend in with his first good NBA team. The Garden crowd adopted him anyway. Every time he jumped off the bench to enter the game, we roared. Every time he sank a jumper, we went bonkers. When he shared the court with Bird, Dave Cowens and Tiny Archibald -- that would be four of the 50 greatest ever -- there was always a sense that something special could happen.

But Maravich had picked up too many bad habits over the years. It was like the Celtics had adopted an abused dog from the pound -- there was just too much damage. After our coach, Bill Fitch, buried him in the 1980 playoffs, The Pistol retired the following fall, missing out on suiting up for the 1981 champs. I remember being particularly crushed by the whole thing. I felt like I'd been given an expensive TV for free, and it had broken down after two months.

|

|

|---|

|

I only knew one person who died on 9/11: Holy Cross alum John Farrell, who graduated in '91 and is remembered by all as a fun-loving, generous, charismatic guy (as well as the master of the garbage put-back layup in pickup hoops). John was blessed with a terrific group of college friends (the Carlin guys), who rallied after his death to make sure nobody would ever forget him. Back in 2002, they started a "Day For Farrell" to raise money for a scholarship in John's name at the Nativity Mission Center in Manhattan (which was fully endowed within two years), then Brooklyn Jesuit Prep (where $75,000 has been raised over the past three years). Now it's become an annual tradition: His friends and family gather in New York to celebrate his life and raise money for John's scholarship fund, which allows underprivileged kids to attend a quality private school. The fifth annual "Day For Farrell" will be held this Saturday (Jan. 27) in Manhattan, kicking off with a memorial mass in the Xavier High School Chapel (12:30 p.m.) and followed by a reception at MJ Armstrong's (19th Street and 1st Avenue) at 2 p.m. that will feature a Final Four raffle and dozens of collectibles, tickets and charity items. There's also a 100-percent chance that A.) there will be beer, and B.) there will be beer. If you're a Holy Cross grad (or anyone else) in the area and you're interested in attending, just show up at one of those locations and follow the herd from there. And if you're interested in giving to Brooklyn Jesuit Prep in John's name, please click here for details. Thanks for reading. |

The point is, Pistol had an impact on me. And that's what the two Maravich books are about -- not his legacy as much as his impact. Kriegel delivers a lyrical look at Pistol's life that is well written and weighty. It's a little full of itself, but big-picture biographies work only when they're written that way. I really liked it. The Federman/Terrill effort isn't crafted as well, but it examines Maravich's life more comprehensively (better research, better detail, tons of pictures). I liked it, too.

It comes down to what you're looking for in a Maravich book. For instance, I couldn't wait to relive Pistol's stint with the Celtics, which Kriegel glossed over and Federman/Terrill recounted in more detail. Any Maravich junkie should read both, but the casual fan curious about Pistol's mystique might be better off with the Kriegel book.

After reading both, I had to admit I had absolutely underestimated Maravich's appeal as a biography subject. A child prodigy with a domineering coach for a father, Pete never seemed happy, even as he broke every conceivable college scoring record. His NBA teammates resented him for his contract and bemoaned his lack of defense, lack of toughness and relative selfishness -- all of which was his father's fault. Pete had been conditioned to shoot 40 times a game in high school and college. Carrying lousy teams, The Pistol never learned to sacrifice his own offense to make everyone else better.

His defining moment was in 1977, when he dropped 68 on the Knicks and fouled out on two dubious charge calls, just another "What if?" moment in a career of them. Poor Pistol could never catch a break. Of course, there is also substantial evidence that he was a drunk and a loon, someone who believed in UFOs and couldn't find peace until he retired and found Christianity in 1982. When he dropped dead at age 40, it was, fittingly, while playing a casual game of pickup hoops.

If you knew nothing about him and glanced at his career stats, you'd never believe he was one of the NBA's 50 Greatest. Even those who revered him have trouble putting his career in context. At dinner recently, my father was perplexed about the existence of two Maravich books until we spent the next few minutes remembering him and inadvertently making the case. Dad recalled that there was usually one nationally televised college game a week in the 1960s, and "you tuned in every weekend praying LSU was on." When my wife asked which current player reminded us of Maravich, Dad's answer was simply, "There will never be another Maravich."

We tried to describe him but couldn't express the experience of watching someone play on a completely different plane from everyone else. He made impossible shots look easy. He saw passing angles his teammates couldn't even imagine. He was the most entertaining player alive, and the most tortured one, as well. You marveled at Pete Maravich, but you worried about him too.

Stick The Pistol in the modern era and he would be the most polarizing figure in sports, someone who combined T.O.'s insanity, A-Rod's devotion to stats and Nash's flair for delighting the crowds. Skip Bayless would blow a blood vessel on "Cold Pizza" screaming about Pistol's ball-hogging. The "SportsCenter" guys would create cute catchphrases for his no-looks. Bloggers would chronicle his bizarre comments and ghastly hairdos. Fantasy owners would revere him as if he were LaDainian Tomlinson or Johan Santana. Nike would launch a line of Pistol shoes. He'd be the subject of more homemade YouTube videos than every other player combined and have a trophy case filled with ESPYs.

Yup, it's safe to say The Pistol was ahead of his time in every respect. And when Hollywood makes a movie about him someday, I hope they stop at one.

Bill Simmons is a columnist for Page 2 and ESPN The Magazine. His book "Now I Can Die In Peace" is available in paperback.