OTL: Fifth-and-goal

ANSAS CITY, Mo. -- Every day, a good-natured insurance man walks into his office restroom to wash his hands. On the walls, all over the john, are the most peculiar memorabilia. There is a matted slab of lime-green artificial turf that is harder than a mallet. There is a photo of a quarterback straining for the end zone. There is a poster signed by two football coaches. There is a down marker with a ridiculous "5" on it.

ANSAS CITY, Mo. -- Every day, a good-natured insurance man walks into his office restroom to wash his hands. On the walls, all over the john, are the most peculiar memorabilia. There is a matted slab of lime-green artificial turf that is harder than a mallet. There is a photo of a quarterback straining for the end zone. There is a poster signed by two football coaches. There is a down marker with a ridiculous "5" on it.

Every time the insurance man is in there, a 20-year-old football game comes rushing back to him. Something vanished that game, something he and college football will never get back. People ask him all the time how he could lose something so bright and loud and shiny -- "How can you lose a down in a football game?" -- and he wants to say, "I plead the fifth." Ha, that would be funny.

Then again, it's been 20 years, and if the insurance man can't laugh at arguably the biggest faux pas in college football history, a faux pas so unthinkable that it flew over the heads of seven referees, dozens of coaches and savvy radio and TV men … then when can he laugh?

So that's why, 20 years later, he keeps what he calls a Wall of Shame in, of all places, his office bathroom.

Because he'd like to flush it.

Inexplicable

He's not the only one. There are men to the north, south, east and west who deal regularly with the same flashback. There's the old coach in Westminster, Colo., who says he's sorry. There's the old coach in El Paso who says he could've called timeout to investigate. There's the old ref in Arkansas City, Kan., who says he was careless. There's the old head linesman in Jenks, Okla., who says it cost him a shot at the NFL. There's the old quarterback in Boulder, Colo., who says he was only following orders. And there's the old center in Denver who says he knew. Or thought he knew. And was told to shut up.

On Oct. 6, 1990, a football game was stolen, and the culprit was … the fates. It was a day when math teachers lost count and sure runners slipped and fell. It was a day when telephones went unanswered and a down marker played tricks with people's minds. If there were an easy explanation, it would've been explained by now. If there were any one villain, he would've surfaced. The consensus, 20 years later, is that it was a once-in-a-lifetime accident, that there will never be another football game that ends on Fifth Down. But only one man from that day is still on the playing field, only one can make sure it never happens again -- at least in his own stadium.

The insurance man.

The other 'U'

Back in the late 1980s, a high-strung Irish coach was building a powerhouse in the Rocky Mountains. He was recruiting the inner cities of Los Angeles and Detroit, waving in farm boys from Coeur D'Alene and teaching them a heartless offense designed to jam the ball down an opponent's throat. Bill McCartney wanted the University of Colorado to run the option better than it had ever been run, and he needed the fastest, slickest, most arrogant players in college football to pull it off. This wasn't going to be your grandpa's Oklahoma wishbone. Coach Mac was going to play-action you to death. He found a swift receiver from Las Vegas, Mike Pritchard, to go with a spunky L.A. running back, Eric Bieniemy. He found a magician of a quarterback from Watts, Darian Hagan, and a backup from the Motor City with a superior arm, Charles Johnson. He found a smart center from St. Louis, Jay Leeuwenburg, who could anchor the line. And he dressed them up in pitch-black uniforms.

In 1989, the Buffaloes were undefeated through the Orange Bowl before losing what was essentially a national title game to Notre Dame and Rocket Ismail 21-6. The devastated CU players made a postgame vow to return to Miami the next year at whatever cost.

One problem: The 1990 schedule was a bear. CU opened at eighth-ranked Tennessee with a tie, lost by a point at 25th-ranked Illinois but seemed to right the ship with a rousing win at 12th-ranked Texas. Teams were gearing up for the Buffs now, putting nine men in the box, and CU was trying too hard to be perfect. Hagan was dealing with a shoulder injury, too. But the Buffs defeated fifth-ranked Washington in Boulder to go 3-1-1 and finally were about to play, in their minds, a cupcake.

Missouri.

Careful what you wish for

The standard line about Mizzou football was: sleeping giant. Based in Columbia, the university had St. Louis to the east and Kansas City to the west, and if the Tigers could just recruit the in-state talent, look out.

They'd had their moments throughout the years. They played in the 1960 and '61 Orange Bowls -- losing to Georgia, beating Navy -- and a guard on those teams was none other than Bill McCartney. Later, Dan Devine took the Tigers to the '70 Orange Bowl. Under Al Onofrio, they upset Bear Bryant's Alabama in '75 and John Robinson in his USC debut in '76. Under Warren Powers in '78, they shut out Joe Montana 3-0 at Notre Dame. Always a big tease, they would turn around and lose to Iowa State.

By 1989, after five straight losing seasons, Missouri brought in a coach from the University of Texas at El Paso, Bob Stull, who had a lot of newfangled ideas. He had a scheme called the jailbreak, where he would spread the field with his receivers, empty his backfield, and throw the ball underneath to anyone and everyone. If it sounded like a precursor to today's spread offense, it was, although a lot of people turned up their noses and dismissed it, run-happy Colorado being one of them.

Still, Missouri's coaches persevered. They had a young Andy Reid, now the Philadelphia Eagles' coach, tutoring the offensive line. They had a young Dirk Koetter, now the Jacksonville Jaguars' offensive coordinator, calling the plays. And they had Stull, a former University of Washington assistant, who had learned from coach Don James never to act rattled on the sideline.

Despite a 2-9 season in '89, Stull was expecting a quantum leap in 1990. At both UMass and UTEP -- his previous coaching stops -- he'd had breakthrough seasons in his second year. And early in 1990, his Tigers torched 21st-ranked Arizona State 30-9 in Columbia, creating unfettered optimism. Their record was 2-2, and with Colorado coming in to Faurot Field next, on Oct. 6, the Show-Me State's fan base couldn't help but say it: We're going to show 'em.

Turf wars

The day broke hot and dry, which had the Missouri grounds crew reaching for its hoses. In most cases you would never, ever water an artificial field before a game, but this wasn't just any field. This was an Oregon field.

The official name was Omniturf, and it was ideal for teams that played in perpetual rain: the University of Oregon and so on. In theory, the turf's sand base would absorb water and give the field better traction on damp days, which was enticing, and not only in the Pacific Northwest. The Midwest had its own share of quagmires, and Missouri -- the last team in the Big Eight with a grass field -- proudly installed the turf in August 1985.

There was a caveat, though: On steamy hot days, the field resembled an ice rink. Not only did it become rock-hard -- tearing skin off players' elbows -- but the footing also was treacherous. In the early fall, the Missouri heat could be numbing, and the grounds crew learned to water the fake field before games and practices to cool it and soften it.

Colorado had won games on the field in 1986 and 1988 with little distress or fanfare. But now, in pregame warm-ups, CU staffers felt the Omniturf was more coarse and unstable than they had remembered. "Of course, I had dress shoes on," says former Buff Dave Logan, who was broadcasting the game that day. "But I was struck by the lack of stickiness of the turf. I mean, everything was very, very smooth. It wasn't a fast track."

Maybe the groundskeepers hadn't hosed the field long enough, or maybe the 82-degree heat was too stifling. But as the game began and Colorado began revving up its option offense, wearing short-pronged cleats akin to basketball sneakers, its players began to fall down. An irked McCartney asked an equipment manager whether the team had brought longer cleats on the trip.

The answer was nope.

Nip and tuck

So that was the equalizer. Missouri's strong-armed quarterback Kent Kiefer had touchdown throws of 19 and 49 yards in the first quarter alone. On a slippery field, it's always the receivers who have the advantage because they know where they're headed. Still, turf or no turf, CU was able to counter with a 29-yard touchdown run by Bieniemy and a 68-yard TD sprint by Pritchard.

At halftime, the score was 14-all. Mizzou climbed ahead 21-17 on a 13-yard run by Mike Jones, the future Rams linebacker who would save Super Bowl XXXIV by tackling the Titans' Kevin Dyson at the goal line. Colorado answered with a 70-yard TD pass from Charles Johnson to Pritchard, and suddenly Missouri's defensive players were the ones complaining about the slick turf. "You couldn't make any quick cuts," Stull says. "Colorado was slipping every time they pitched on the option; they had a hard time making corners. But so did we. We had a hard time rushing the passer."

The teams exchanged field goals, and it began to look as if the last team to have the ball would win. With 2:32 left in the game, Missouri dialed up its jailbreak screen, and receiver Damon Mays darted 38 yards for the score. The Tigers led 31-27. They then kicked off to the Buffaloes, who were called for a clip on the return. The referee from Arkansas City, Kan., J.C. Louderback, marched the ball back to the CU 12-yard line. When he announced the penalty over his mike, his voice seemed strong and true; no one gave him a second thought. He and his crew had been anonymous all day, just how Louderback liked it. There's nothing a ref loves more than dreamy anonymity.

Strangers

The truth was, it was remarkable that the officiating crew was holding it together. It was a split crew, meaning the seven of them didn't work together every week, and a few hadn't even been introduced until 10 that morning. They hailed from Kansas, Oklahoma, Nebraska and Missouri, and although that might not seem terribly significant, the head linesman -- Ron Demaree from Jenks, Okla. -- remembers worrying that there might be a "major" lack of communication that day. "Because you don't know what's inside a guy's head, where they're going to be on the field," Demaree says. Demaree felt that a great officiating crew had to know one another like the back of their hands, and he meant that literally.

Something as simple as changing the down marker from first to second down had to be done somewhat blindly. The protocol would be for Louderback to quickly signal second down to Demaree, and Demaree would follow up by signaling second down -- sometimes behind his head -- to the man holding the down marker. "I will not 100 percent of the time turn and look at the box man," Demaree says. "Because you could have players coming to the line of scrimmage, ready for the snap. And just my philosophy was that's not a good thing to do -- turn your back to the field."

For that reason, Demaree always made sure to visit with the head of the chain crew before the game just to let him know how he was going to handle a change of downs. It was just another minor but necessary detail because the chain gang is not part of the officiating crew. It's hired by the home team, which means it's also usually nuts for the home team.

But on this day, it was the other refs Demaree was wary about. He had worked with the man on the down marker countless times before -- Rich Montgomery, a Missouri alumnus, a hopeless Tigers fan but a conscientious worker. He knew Montgomery was the type of person who would have his back.

Because, after all, Montgomery was an insurance man.

Spike TV

The final drive began with Johnson shuffling into the Colorado huddle, 88 yards from the goal line, telling his teammates they all would be prancing in the end zone soon. He had started the game ahead of injured Hagan, and for a relative neophyte, he had a lot of nerve.

Early in the drive, he faced a third-and-11 at his own 23 and found Rico Smith for 22 yards over the middle. Johnson exhaled. Now he was certain the Buffs would score. Bieniemy ran for 7 and 15 yards, and with 36 seconds left, they were on the Tigers' 9-yard line. On the Missouri sideline, Stull could tell his defense was winded. He quickly called timeout, to give his players a water break if nothing else.

On the field, Louderback noticed that the clock operator had run two extra seconds off the scoreboard. While Stull and McCartney were drawing up strategy, Louderback ordered the clock reset to 38 seconds. No one thought anything of it; it was just two lousy ticks.

After the timeout, Johnson ran a play fake, rolled right and saw his tight end, Jon Boman, in the absolute clear near the sideline.

"Anybody in America would've scored," McCartney says.

"We all finally breathed a sigh of relief -- and then a gust of wind or something, he just fell," Buffs center Leeuwenburg remembers.

"I thought, 'Oh well, we still got a chance -- maybe the gods are on our side today,'" Montgomery says.

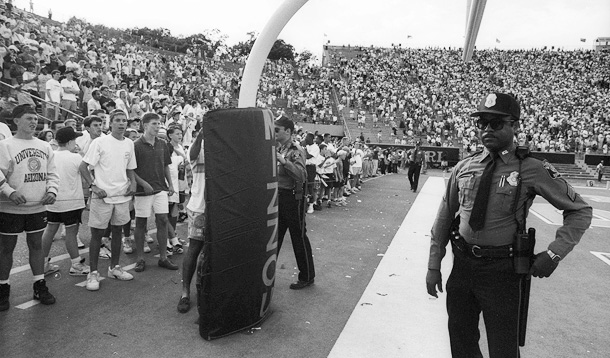

The insurance man rushed to the 3-yard line to set his down marker to first down. But the rest of his chain crew disappeared. For safety reasons, the Big Eight had instituted a new rule in goal-to-go situations, forcing the men carrying the chains to move off the sideline. Only the box man would remain. Rich Montgomery was on his own.

Johnson rushed to the line to spike the ball with 28 seconds left. Here was another new rule, one that allowed quarterbacks the chance simply to throw the ball down on the turf to stop the clock. In previous years, they'd had to throw the ball out of bounds or at a receiver's feet to stop the clock. Some of the CU-Missouri referees had never seen this done before.

After the spike, Louderback signaled Demaree for the change of down, then Demaree signaled Montgomery. The two key officials, Louderback and Demaree, had caught it. They both moved the rubber bands on their hands from their forefinger to their second finger, signifying second down. Rubber bands were the way most referees kept track of which down it was. But not every official had a rubber band that day, and not all of them -- especially the refs on the defensive side of the ball -- had clearly seen the spike. Some thought that the ball had been inadvertently kicked and reset; that happens all the time. "We did change the down, but everyone's mind didn't let it change," Louderback says.

On second down from the 3, with still the 28 seconds left, Johnson handed off to Bieniemy, who surged up the gut to the 1-yard line. Colorado's fullback, the 230-pound George Hemingway, got in Louderback's face to say, "Timeout! Timeout! Time! Time!" Louderback remembers the fullback just howling, remembers being startled by it. But he snapped out of it and walked to the CU bench to alert McCartney that it was his final timeout.

Problem was, he forgot to signal third down to Demaree. And Demaree, to this day, isn't quite sure what he did next. He thinks he signaled third down behind his head to Montgomery, that he just took care of the matter himself. But Montgomery swears he never saw it. Instead, he had been peering across the field at Louderback on the CU sideline, waiting for Louderback's signal, a signal that never came. And then Montgomery's attention began to drift.

Because behind the CU bench, a man was dying.

Fatal excitement

That whole last drive, the crowd had been on its feet, frenetic. Throw in the 80-degree heat, and someone was bound to be overcome.

Cheryl Hines, a Missouri fan sitting on the 40-yard line, 22 rows up from the Colorado bench, remembers the stadium noise reaching a pinnacle after Boman's catch-and-slip. Then, after Johnson's first-down spike, she says she felt a forceful bump on her shoulder. A heavyset man sitting behind her had collapsed and was now unconscious in her lap. She realized right away that he was having a heart attack. Two of her friends seated nearby were in medical school and began performing CPR. Someone rushed to the field to alert an EMT. That whole section of the stadium had to get up and move to give the emergency workers room. Montgomery watched it all.

The heart attack victim was transported to the Faurot Field track during the timeout, as the EMTs performed CPR. "I'd like to say I wasn't distracted," Montgomery says. "But even most of the Colorado players were turned around looking."

Normally, if a referee doesn't signal a change of down, Montgomery will ask the head linesman what to do; by rule, he can't switch downs on his own. But, perhaps because of the heart attack, he failed to ask. And because of a whole different sort of mayhem on the CU sideline, Louderback was just as much in the dark.

When the referee rushed over to tell McCartney he was out of timeouts -- with 18 seconds left in the game -- the coach looked at the down marker and the scoreboard, which both mistakenly still said second down. At that point, Coach Mac waved Louderback over to tell him the Buffaloes were going to run three plays -- a run up the middle, a spike and then another run. He wanted to make certain that Louderback didn't allow Missouri defenders, after the first play, to sit on the CU ball carrier, preventing the Buffaloes from lining up for the spike in time. Johnson says he heard Louderback tell Mac, "You'll be fine."

But that little conversation unintentionally seemed to cement in Louderback's mind that it was still second down. McCartney had lost track himself, and by telling the referee he was running three more plays, Louderback, a math teacher during the week, lost count, as well.

Out on the field, meanwhile, head linesman Demaree just assumed Montgomery had switched to third down. He swears he moved his rubber band over to his third finger, but he didn't turn to look at the scoreboard or the box to make sure, and none of the other officials -- possibly discombobulated by the spike -- corrected a thing. To everyone on the playing field, it was still second-and-goal with 18 seconds left.

But behind Montgomery on the sideline, a 7-foot man began to go bonkers.

The voices that roared

They weren't playing this game in a vacuum. Up in the TV booth, the color analyst Dave Logan, a former Buff and Cleveland Browns receiver, was squinching his eyes and questioning the down marker. He told his broadcast partner, Les Shapiro, that he thought it was third down, not second. But he didn't press it, saying that it was a moot point, that there wasn't enough time to run three plays anyway.

Over in the Missouri radio booth, a popular KMOX announcer, Bill Wilkerson, was a tad more pointed and began to percolate the ire of any Missouri fan who was tuned in: "Second-and-goal at the 1. That's what the stick says. I thought it was third-and-goal. It's got to be third-and-goal. The stick says second. And so does the scoreboard. Apparently, I'm wrong; it says second-and-goal."

Saturday's Game

No. 24 Missouri will host Colorado on Saturday, 7 p.m. ET.

Big 12 blog: ESPN.com's David Ubben writes about all things Big 12 in his conference blog.

Wilkerson couldn't run this thought by his broadcast partner -- former Mizzou basketball player Tom Dore -- because Dore already had headed down to the sideline for the postgame coach's show. But 7-foot Dore did have a headset on and could hear Wilkerson's ruminations. So Dore began to jabber at Montgomery, who was just 2 yards away: "Hey, it's third down, not second down," Dore claims he said. "You forgot to change the down marker. You missed this!"

Montgomery claims he didn't hear Dore, but the fact is, confusion was starting to build all over Faurot Field. As the CU timeout was expiring, McCartney pulled all the Buffaloes players together to explain that they were running three plays: a run, a spike and a run. All of them nodded except Leeuwenburg.

As the starting center -- and team brain -- it was Leeuwenburg's job to always know the down and distance. So he raised his hand to say, "I don't think we can do that, Coach. I think that's going to be fourth down when we spike the ball."

McCartney's response: "Shut up and play center, Leeuwenburg."

What was the center supposed to do? McCartney's veins were popping out; the coach was adamant it was second down. The center figured that the spike must have been blown dead or that the timeout had come before the second-down snap. How could all these professionals be wrong? How could two sidelines, a box man and seven refs all swing and miss?

So, he just shut up and snapped the ball.

Six seconds of pure frustration

After the timeout, Colorado got its second second down. Johnson again handed off to Bieniemy, who dove for the end zone but was stopped short at the 1. The clock was still running; CU was out of timeouts; and, up in the booth, Wilkerson was howling:

"No! No! No! He did not get in. Tremendous charge. Tremendous charge. 9, 8, 7 … the clock has been stopped. Why? Why is the clock stopped? 7, 6, 5, 4, 3 …"

Just as McCartney had hoped, Louderback and his crew had halted the clock for six full seconds to let the players unpile. The Missouri bench was incensed; the Tigers could see no clear evidence of their players holding Bieniemy or Buffaloes linemen down. They felt the game clock should've expired. But Johnson now had time to take the snap and down the ball … with two seconds left, the two seconds Louderback had restored what seemed like years earlier.

Pandemonium set in. Fans were crowding the sideline, ready to yank down a goalpost. There would be one final play. Or would there?

Three feet behind Montgomery, Dore was now beside himself, shouting at the insurance man: "Hey, it's fifth down! It is fifth down! It's Missouri's ball! They spiked the ball on fourth down! You have to stop this game! There are only four downs in football! This is fifth down!"

Montgomery says he heard nothing as he stared straight ahead. "I bleed black and gold," he says, "and I guarantee if I'd known about it, I would've said something." He claims that the Missouri fans who were creeping toward the field distracted him. He says he was worried about getting trampled. He says the crowd noise was palpable.

But the fact is, the crowd was chanting "Fifth down," too. The fans were bellowing it at the refs, and they were hollering it at the Missouri coaches, who seemed perplexed themselves. Caught up in the moment, Stull had lost track of the downs. But Andy Reid and another assistant, Steve Telander, began grumbling that the spike might have come on fourth down. The Tigers' backup quarterback, a 4.0 student named Phil Johnson, also tugged on the coach's sleeve, saying, "Fifth down." But no one seemed indignant about it. No one was sprinting on the field, waving his arms, kidnapping the football.

The play clock for down No. 5 was winding down, and Stull contemplated calling his last timeout to sort it all out. But first he looked down toward Montgomery, one of the most rabid Tigers fans he knew. Montgomery's personalized license plate read "BGTIGR." If anyone was going to protect Stull's interests, it would be Montgomery. "He was my guy," Stull says. "I mean, you cut his arms, little Tigers run out, OK? But he's standing there. There doesn't seem to be any problem with him."

Dore remembers that same helpless look on Stull's face, remembers thinking Stull was looking down to him for advice. Dore hosted Stull's postgame coach's show. They were pals, too. But Dore didn't know what to do or say. He wanted to flash a timeout signal to the coach, but he was frozen. "Bob's mouth was open, his eyes very wide," Dore says. "But I'm sure in Bob's mind it was, 'These guys are not going to make this kind of mistake. This can't happen.'"

Stull's split-second decision was to forgo the timeout. He was worried that if he called time and was wrong about the number of downs, Colorado would be able to set up a well-conceived play and score easily. Or if he ran onto the field and waved his arms hysterically, he was concerned about getting a penalty, moving CU half the distance closer to the goal line. But if he made the Buffaloes just run a play, with a backup quarterback staring into a hostile crowd … maybe that was the ticket. He told his defensive coaches, "Even if it's 10th down, we've got to stop 'em. Let's stop 'em."

And maybe they did.

Did he or didn't he?

Who has a fifth-down play in his playbook? Colorado didn't. But the Buffaloes' huddle -- all but a suspicious Leeuwenburg -- still thought it was fourth down, and they were going to run their bread and butter: the option.

The play was named "38 Block H," and it called for Johnson to either pitch wide to Bieniemy or improvise himself. But he was frightened of the turf, didn't want the game to end with another catastrophic slip. So after taking the snap, he took a trio of baby steps to the right and burrowed straight for the end zone. He took a direct hit, twisted and started falling back-first to the turf. He seemed to land on his shoulder blades, a hair short of the goal line, with the ball on his chest. Under that scenario, it's no touchdown. But, as he hit the turf, Johnson had the wherewithal to arch his lower back and reach the ball over the goal line. Photos taken by the Columbia Daily Tribune showed him short of the end zone. But photos taken by Sports Illustrated showed him conceivably in. Video was inconclusive, and there wasn't instant replay back then, anyway. What there was … was Ron Demaree.

At first, not one official on the field signaled touchdown. But Demaree, standing a few feet in front of Montgomery on the Missouri sideline, ran three … four … five … six steps in, found the ball over the goal line and threw his arms up. Right away, Demaree was nearly tackled by an angry Missouri defensive back, Harry Colon. After that, it was a free-for-all. A mob of Missouri fans rushed the end zone -- half of them to tear down the goalposts, thinking they'd won, the other half to tell Demaree, "That was fifth down!"

Demaree heard them loud and clear, and his mind began to race. After the second second down, he had properly moved his rubber band to his fourth finger, meaning he should've known Johnson's ensuing spike was the last down. But before the spike, he had seen Louderback signal third down. He had noticed third down on the scoreboard and on Montgomery's box. "So I pulled my rubber band back to three, thinking I was the only one wrong out of the bunch," Demaree says. "I just didn't trust my rubber band."

Of course, now that the fans were yelling fifth down, Demaree went scrambling to find Louderback for clarification. And Louderback wasn't sure about anything now. Immediately after the touchdown, Louderback says a "little old man" had accosted him at midfield, saying, "You screwed this one up! You allowed them five downs!" Louderback told him, "Get the heck out of here," but it panicked him nonetheless.

When he and Demaree spoke on the field after the touchdown, Demaree said, "J.C., I think we've got a fifth-down situation here, or at least the students do."

"What do you show?" Louderback asked.

"I'm showing four, not a five," Demaree said. "But I could be wrong."

By now, Colorado and Missouri were already in their locker rooms, thinking the final score was 33-31. The TV broadcast was already off the air. But in the middle of Faurot Field, Louderback was standing with his six other officials, taking a poll. "Do any of you guys recall us allowing too many downs?" he asked. "We better get this right, or it's going to get ugly."

They compared rubber bands but Demaree says not one of them could confirm there'd been five downs. The two spikes had played tricks with their minds. Louderback went to a sideline phone to call the Big Eight observer in the press box, but nobody answered because the observer had been on an elevator to the field during the whole five-down sequence. The liaison to the TV booth was no help, either, because the broadcast was over and he had packed up his headset. Louderback was on his own.

The ref never called the press box because he says it wasn't protocol. But if he had, he would've received some colorful responses. Writers and sports information directors seemed to be on top of the mistake; Colorado's Dave Plati had shouted an F-bomb when Johnson spiked the ball on the real fourth down. And when Buffaloes offensive coordinator Gerry DiNardo stopped by the CU radio booth, where Plati was sitting, the coach asked, "How many plays did we just run there?"

"I think five," Plati said.

Eventually, after close to 20 minutes, a pale Louderback made a decision. He wanted the teams back on the field.

Misery (and Missouri) loves company

Leeuwenburg, in front of his locker, was already ripping tape off his wrists. He had bumped into DiNardo in the locker room and had asked the coordinator, "Gerry, did you know?"

DiNardo, having already bumped into Plati, answered, "Jay, it's my job to know." Which is when Leeuwenburg realized he'd been right all along.

A few minutes later, the Buffaloes learned of Louderback's request. He was ordering them back onto the field for an extra-point attempt. The fifth down Louderback still wasn't sure about. But in college football, a team can score two points if it returns a blocked PAT for a touchdown. So he waved both squads back.

Stull had spoken to Dore by then and had been informed again of the possible fifth down. But no one on the Mizzou staff could document this to Louderback on paper. Demaree says he asked the Tigers' bench whether it had a staffer who charted plays. He was told it did, but Demaree says the kid had been caught up in the tension of the final drive and had stopped keeping track.

Even if there had been a fifth down, Louderback was under the impression that Missouri would've had to dispute it before the actual play. He did not believe it was a correctable error under NCAA rules. And this was all part of what he relayed to Stull, who, true to his Don James roots, stayed relatively under control. The fact was, he still wasn't 100 percent certain of the fifth down.

"I tried to keep my composure because we didn't know for sure," Stull says. "Some of our coaches and players had argued the point before the fifth-down play, and then we went back and challenged it even more after. But nobody had the answer, and the officials were still convinced they were right. My point to them was, 'You better be right because if you're not, it's not gonna be pretty.'"

It was ugly, all right. McCartney told his offensive unit to go back out there and kneel on the ball, to not even risk a blocked kick. So 11 Colorado players walked back onto a football field that was covered in hate. "That was the most insane one play of football I've ever been a part of," Leeuwenburg says of the extra-point play. "We had the 11 starters on our offense go out; everyone else stayed in the locker room. And at this point, we knew we had gotten five downs. After we'd taken a knee and were running off the field, we had a circle of police around us, and there was a guy that came up and he was so furious, he had something in his hand. I don't know if it was a bottle or a battery, but he was trying to go for one of our players and knocked a cop out. I can remember four cops just beating the hell out of this guy. It scared me to death. I thought there was truly a chance I wouldn't make it back to the locker room."

On his way off the field, Montgomery crossed paths with Louderback. They were moving quickly -- escorted by police -- and Louderback told Montgomery, "They're saying we had an extra down."

"No way," Montgomery answered. "No way."

In his postgame news conference, McCartney only exacerbated matters. Rather than admit that a fifth-down scoring play was a regrettable error, he ranted about the field conditions, saying Missouri should've alerted his staff ahead of time so it could've brought the proper cleats. He said he wasn't going to forfeit because had he known it was third down during that timeout, he'd have called just two plays -- a pass and then a run. But considering he was a Missouri alumnus, considering he'd been a sore winner, considering he was founder of the moral religious group, Promise Keepers, he was crucified nationally. Called a hypocrite, and worse.

It was a somber day all around. The unidentified man who'd suffered the heart attack died. Fans pelted the referees' locker room with rocks. Demaree heard definitive word about the fifth down while driving to St. Louis that night on business, listening to Wilkerson's postgame show. He ended up getting a death threat at home. He became depressed. An NFL official actually had been in the stands that day evaluating him, but he never heard from the league again. The next day, he offered to resign.

Louderback drove home to Kansas after the game and didn't arrive until close to midnight. His wife had taped the game, and as he watched the final seconds, he realized he was going to live in infamy. Why hadn't anyone helped him? Why hadn't the other refs realized his mistake? Why hadn't the Missouri coaches caught on? Why did that tight end have to slip when he could've waltzed into the end zone? Why didn't the Big Eight observer stay in the press box? Why was there that new rule removing other members of the chain gang from the sideline, leaving Montgomery there by himself? Why … why … had he put those two harmless seconds back on the clock in the middle of the final drive? That last one ate at him. Fifth down had taken place with two seconds left. If he had never changed the clock from 36 to 38 seconds -- when no one was looking -- fifth down never would have happened.

As for Montgomery, he drove home to Kansas City with his oldest son, Jeff, a former Missouri walk-on who was in his first year on the chain crew. They were pulling onto I-70 West, about to leave Columbia, when they, too, heard Wilkerson recount the five downs. Rich felt sick. It dawned on him that a Missouri man had helped cost Missouri a game, that "BGTIGR" had hurt the place he loved the most.

Montgomery pulled over, got out of the car and threw up.

Life goes on

Colorado didn't lose again that season, and, in the Orange Bowl, it took a rematch with Notre Dame to become co-national champion with Georgia Tech.

The Buffs were more than deserving. They had future NFL players such as Pritchard, Alfred Williams, Chad Brown and Deon Figures. They had played a wicked schedule. They had blasted Nebraska by 15 points on the road. But they also had been 1-for-1 on fifth-down conversions.

McCartney and his staff didn't want to hear that their title was tarnished, and they continued to harbor resentment over the way they were portrayed. When Mizzou came to Boulder the next season, the staff considered punting to the Tigers on a third down -- "To say, 'Here's your friggin' down back,'" Plati says -- but instead simply pummeled them 55-7.

Clearly, the incident was still resonating. The entire fifth-down officiating crew was suspended for a week, and, not long after, Demaree and Louderback -- who'd been 57 and 56, respectively, in 1990 -- reached the Big Eight Conference's retirement age and were replaced. Demaree, whose regular job was with the phone company, actually got transferred from Oklahoma to Missouri at one point. "It wasn't easy living in Missouri as the 'fifth-down man,'" he says. "But when I'm wrong, I'm wrong. If you screw up, you pay the piper."

Louderback went on to officiate in Conference USA, got to do an Army-Navy game. All in all, he had a stellar career. He had calmly refereed the infamous 1986 Oklahoma-Miami game, where police dogs were needed to quell a fight on the field. He had never made excuses about the extra down. By and large, his reputation hadn't been trashed.

It was actually Charles Johnson who ended up living the charmed life. He didn't start another game that 1990 regular season, but replaced Hagan in the ensuing Orange Bowl against Notre Dame and took home MVP honors after leading the team to the winning touchdown. He later became a sports talk radio host. As for Leeuwenburg, he wound up playing nine seasons in the NFL and, predictably, became a third-grade teacher at a private school in Denver -- where he makes sure his students never lose count.

Stull never really recovered from the gaffe. Missouri won only two more games in 1990 to finish 4-7, then followed with 3-7-1, 3-8 and 3-7-1 seasons. He knew his offensive system worked (and his friend and fellow James disciple Gary Pinkel would make it work at Mizzou years later). But not only did Missouri fire Stull after the '93 season but it also fired the Omniturf with him.

The next Tigers coach, Larry Smith, wanted a grass field, and a Rolling Stones concert at Faurot Field in September '94 helped the Mizzou administration raise $100,000 to help pay for the sod. A sordid era was over, and Jeff Montgomery, who had become a graduate assistant under Smith, asked whether he could take a piece of the Omniturf home.

He gave it to his dad, who chuckled and had it framed. The truth was, Rich Montgomery was carrying on. Jeff says he thought his dad might not be invited back to run the chain crew, but the pink slip never came. Demaree and Louderback had taken full responsibility, and Stull liked Montgomery and had never held a grudge. Montgomery returned for the 1991 season, and began to look back at Oct. 6, 1990, with a wan smile.

He asked Stull to autograph a fifth-down poster he had, and the coach -- who is now the AD at UTEP -- signed it, "Rich, did you know?" Montgomery took the same poster to a Promise Keepers event and introduced himself to McCartney.

"I was the box man for the fifth-down game," Montgomery said.

"You?" McCartney asked.

The coach signed the poster: "They tend to even out." But as the years passed, McCartney softened … and softened. And now he sits in his Westminster, Colo., home, apologizing, wishing he could take back all his indignation for the Omniturf. "I went to school at Missouri, OK?" McCartney says. "I'm an alum, OK? And all of this has tarnished that. That is a regret that I'll carry with me to my grave. I wasn't gracious in victory. When you win, be humble. You know? So I say this to all the people of Missouri, I'm sorry for the way I behaved. I behaved with immaturity. I should've handled that graciously, and I regret I didn't uphold the tradition of being a Missouri Tiger better in that time of struggle."

Twenty long years later, the one who seems most at peace is Montgomery. At his State Farm insurance agency, he'll give friends a tour of the Wall of Shame in his bathroom: the signed poster … the slab of Omniturf … the photo of Charles Johnson … the specially made fifth-down marker.

Maybe it's easier for him because he has a game almost every Saturday. Twenty long years later, Montgomery is still carrying the downs marker at the University of Missouri … joined on the chain crew by his two sons, Jeff and Mark.

All the head linesmen know Rich Montgomery by name. They all say, "No fifth downs" in their pregame meetings, and to this day, Montgomery and his two sons meet in the end zone before every Faurot Field kickoff to fist-bump and say, "Break a leg. Let's keep it at four."

But just to be certain, Montgomery uses a magic marker to keep track of every play.

Insurance.

Tom Friend is a senior writer at ESPN.com.Join the conversation about "Fifth and Goal."