OTL: The Redemption of Billy Cannon

NGOLA, La. -- The prison dentist walks slowly down the gravel road past the warden's house. He is stooped, with a big belly, two white tufts of hair and a bald spot. He's got a bulbous nose and a creak in his step. But look closer. There are still pieces of the man he used to be. He moves with a subtle feline grace. He's got the deepest blue eyes, familiar somehow, like an old photograph. They seem to only absorb information, never giving anything away. He's alone, carefully making his way from the party to his white Ford truck. He's been on display long enough.

NGOLA, La. -- The prison dentist walks slowly down the gravel road past the warden's house. He is stooped, with a big belly, two white tufts of hair and a bald spot. He's got a bulbous nose and a creak in his step. But look closer. There are still pieces of the man he used to be. He moves with a subtle feline grace. He's got the deepest blue eyes, familiar somehow, like an old photograph. They seem to only absorb information, never giving anything away. He's alone, carefully making his way from the party to his white Ford truck. He's been on display long enough.

"I'm going to play with my horses," Dr. Billy Cannon says.

Even in his 72nd year, people can't help looking at him. They see only the broadest strokes: the LSU football hero who fell unimaginably far. Almost no one is allowed to see deeper. He doesn't like to be inspected -- once he saw me taking notes in a hotel lobby and barked, "Put that damn book up" -- because his life then becomes the property of the observer.

Of course, what he likes hasn't mattered for a long time now. For the past half century, he has existed mostly through the eyes of others, the narrative of his life in their control. They stare, they whisper, they point. They wonder what to make of his hard exterior, or the gruff responses he gives to strangers, or the fact that he has spent much of the past two decades in virtual seclusion. For years, the few people he allowed to come close were left with more questions than answers. Does he know who he is? Does he know what he means? Are his days filled with regret? Strangers yearn to know him, yet he seems unknowable, to the men who played with him, maybe even to himself. He gave me more time than he's ever given a writer before, and for every moment I thought I understood him, there were two more that made me sure I didn't know what he thought about anything. His own college coach says he didn't really like the younger, more arrogant version of this old man inching down the hill.

Still, people keep trying, like the guy earlier today, at the party before the annual prison rodeo. He spotted the dentist across the warden's front yard, began the slow but inevitable dance over, until, finally, they stood just feet apart.

"Are you Billy Cannon?" he asked.

"I'm what's left of him," the dentist said.

Recently, I invited the current LSU running back to watch The Punt Return. No other description is needed, and Charles Scott walks into the Tigers' team meeting room, ready for the video of Billy Cannon's 1959 Halloween run. I ask him if he's ever seen it before.

"Come on now," he says.

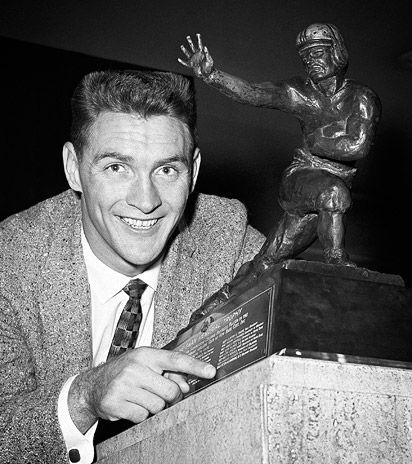

Of course. He's one of a billion to hear or see and marvel at this run in the 50 years since Cannon took that Ole Miss kick 89 yards to win the game and lock up the Heisman Trophy. The audio still plays on Louisiana radio, the video on television. Fans paint murals of the play on the sides of RVs. Once, in the hall of a New York hotel, I heard SEC basketball announcer Joe Dean, Jr., do the radio play-by-play verbatim. "The thing became a religious situation," says Paul Dietzel, Cannon's college coach.

The black and white flickers, and Scott sees the familiar beginning: the ball bouncing at the 16, Cannon ignoring his coach's rule about catching balls that close to the end zone and fielding it at the 11, turning upfield. At the 20, he meets the first group of tacklers. He runs through them, legs pumping.

"Wow," Scott says softly.

Cannon breaks the second tackle, then the third, then the fourth, fifth, sixth. Scott can't believe how small a crack Cannon needs. The two running backs met once, a year or so ago.

"I brought a picture of me," Cannon told him then. "If you don't appreciate it, your daddy will."

"Oh, I appreciate it," Scott said. "Trust me."

Scott saw through the old body and white, thinning hair. He saw what a lion Cannon must have been, recognized the things that don't ever leave a star.

"He has swag," Scott says now.

On the screen in the LSU meeting room, Cannon breaks free, as he always does, running alone down the sideline. Scott is like generations of Tigers who've seen The Punt Return and dreamed of becoming legends themselves, too young to realize what something like that costs. "When you look at a play like that Halloween run," Scott says, "you get a picture of yourself doing something that people remember forever."

Once, Cannon was like Scott: young and strong, invincible, sure he could handle being a hero on Saturday night. After reaching the end zone 50 years ago, he limped toward the sideline, no doubt thinking the hardest part of running that punt back was finished. The radio announcer said, "Listen to the cheer for Billy Cannon as he comes off the field. Great All-American." The crowd's roar will make the hair stand up on your arm.

Late in the fourth quarter, Cannon led a goal-line stand and made the game-saving tackle. Exhausted, he lay down in the tunnel, unable to make it to the locker room. Finally, he sprawled out on a training table, holding an ice pack to his bruised face. He gave credit to his blockers, changed into street clothes and left for a double-date with his quarterback, Warren Rabb. They pulled up to a blue-collar joint on the tough side of Baton Rouge, near where Cannon grew up the son of a janitor, in the shadow of the refineries.

When they walked through the door, the place buzzed with excitement. The conqueror had arrived. People came to the table all night, in awe. Cannon seemed uncomfortable with the attention, Rabb would remember, and didn't really want to talk about the run. His life was changing in that room, at that table, and there was nothing he could do to stop it. Folks imagined anyone capable of heroics must be a hero, and he was treated that way. Eating dinner, with people pushing and crowding just to touch him, did he realize they didn't love him as much as they loved his run? Did he realize he was beginning a new journey, one that would take the rest of his life to complete?

The men who played with Billy Cannon are old now, still answering questions about The Punt Return. They try their best to tell fascinating stories about those years, but a common thread emerges: These aren't stories of things they did with Billy, they're stories of things they watched Billy do.

Mostly, they watched him perform mythic feats of strength. Once, in a track meet, he ran the 100-yard dash in 9.4 seconds and threw the shot 54 feet. He knocked a defender cold with a forearm. He took a kickoff back at Texas Tech as a sophomore, and when he reached the end zone, only nine seconds had run off the clock. The play stunned opposing players and mascot alike. "That damn black horse," teammate Scooter Purvis says, "he was even looking at Cannon."

Cannon married as a freshman and lived in married student housing. His teammates saw him in practice and in meetings, but few felt as if they ever saw inside. Looking back, they realize they didn't really know him at all. Even then, he was a mystery. Dietzel describes him as "aloof" and "not one of the guys."

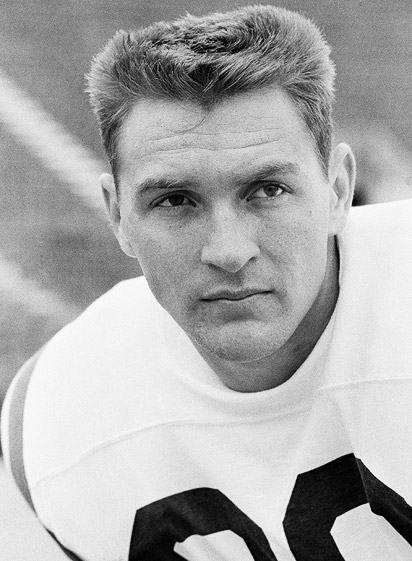

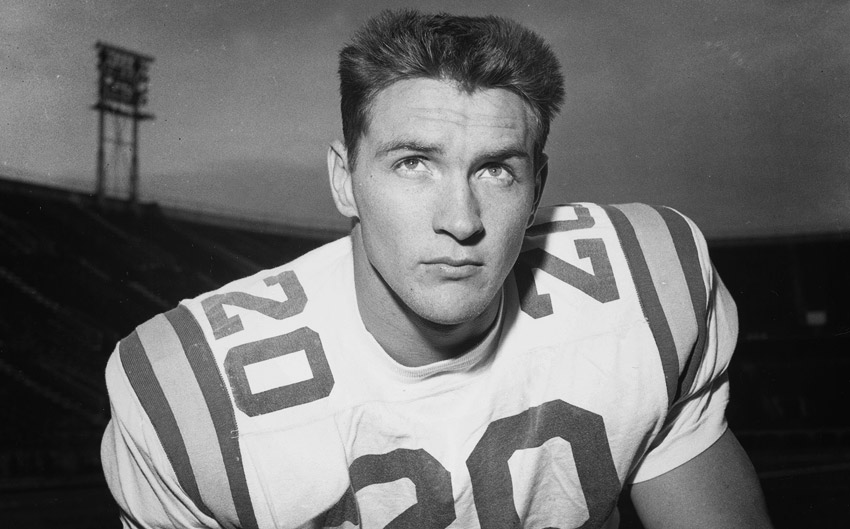

They were college boys. He was a man. In high school, they all heard, he got arrested for going downtown and beating up local gay men for fun. They heard whispers he worked for and ran with local union leaders and suspected mafia bosses. He didn't seem to be controlled by the mundane human emotions and fears that consumed their lives. Before a game, the story goes, a shaky teammate asked Billy if he was nervous. Cannon, who made money by selling off an entire section of Tiger Stadium seats, looked up and saw his area full. He smiled. No, he said, he wasn't nervous a bit. There are dozens of stories like that, and who knows now whether they are true. But they all have the same center: Rules did not apply when you could run the ball like Billy Cannon. He had movie-star looks; 50 years later, two coeds saw his framed college-aged picture, with that F-You jaw and unknowable eyes, and one gushed, "What a stud!"

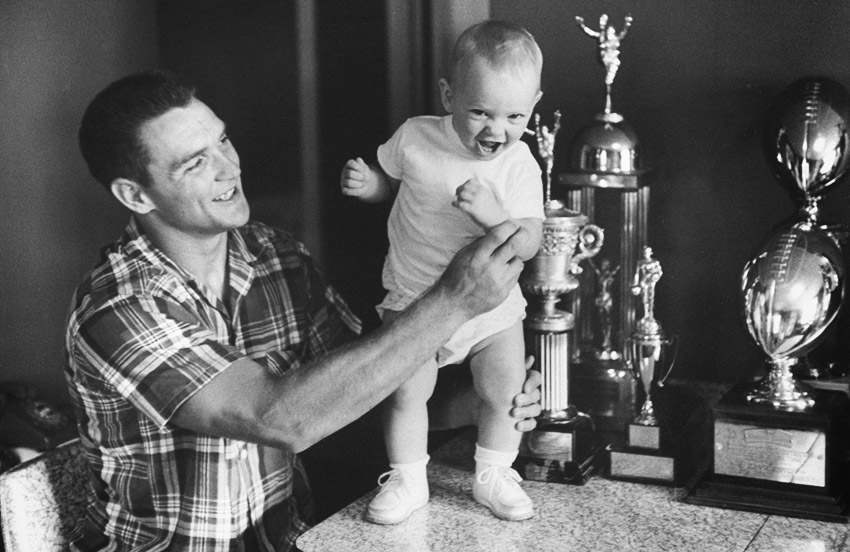

After college, he signed with both the AFL and the NFL, prompting a lawsuit. He played 11 years in the pros, with Houston, Oakland and Kansas City, then came home to become an orthodontist. Every kid in Louisiana wanted to have their teeth fixed by Billy Cannon. The cash rolled in. But not everything was magical: He publicly criticized Charles McClendon, the LSU coach, and people imagined him arrogant, though their baseline of comparison was the icon they had constructed in the first place; Billy was judged against a person he never claimed to be. Regardless, the boy who grew up poor found himself welcome in all the private clubs, with more money than he'd ever imagined, married to his high school sweetheart, Dot, with five healthy, well-adjusted kids. In 1983, he was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame. Everything seemed so easy.

Maybe, his closest friends would think in years to come, too easy.

On July 9, 1983, after a lengthy surveillance, the U.S. Secret Service knocked on Dr. Billy Cannon's door, and suddenly nothing seemed too easy anymore.

The dark news spread all over the state. Cannon, hero of Halloween night, favorite of children all over Louisiana, had been arrested for counterfeiting. He and a gang of friends turned amateurish crooks manufactured more than $6 million in $100 bills. They'd passed several hundred thousand into circulation, and Cannon buried the rest of the fake money in Igloo coolers. It was the seventh largest counterfeiting scheme in U.S. history. Prosecutors called Cannon the ringleader.

He immediately confessed.

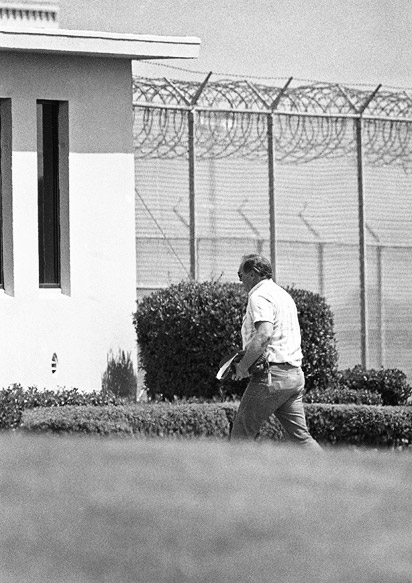

A different Billy Cannon emerged in the months that followed. People read stories of investments turned sour and of properties auctioned by the sheriff. They tuned into the news to see him walking through a phalanx of cameramen, his lawyer pushing the aggressive ones aside. Over and over, people asked why. Over and over, he declined to answer. He stared straight ahead, giving away nothing, more of a mystery than ever.

Finally, Cannon stood before the judge to be sentenced. He got five years.

Cannon left the courthouse via a back door, took off his suit jacket and, wearing a short-sleeve dress shirt, climbed into the backseat of a waiting car. Only cameras witnessed his exit, none of the usual fans or kids pleading for autographs. Stories ran about fathers not telling their sons the news. The state felt betrayed. Cannon had broken faith with the people, and they broke faith with him in return. A stadium of fans once stood to see him run down the sideline, but people remember only a single member of the LSU family, longtime sports information director Paul Manasseh, showing up in the courtroom to support him.

The world couldn't run from Billy Cannon fast enough. The College Football Hall of Fame rescinded its honor. Time Magazine called him "A Bogus Hero." His greatest moment -- The Punt Return -- became the source of his humiliation. They showed it over and over again, not in celebration, but to set up his downfall. Something strange began happening: The fans who loved him because of The Punt Return found they could continue to idolize the moment while rejecting the man. They didn't need Billy Cannon. They just needed the run.

The feds took him to a minimum-security facility in Texas, and the "CBS Evening News" broadcast his walk from a two-tone Ford van into the prison. He wore jeans and carried something small under his left arm. The news cut from the prison to The Punt Return, and the reporter's closing words sounded like a eulogy: "LSU faithful say they will fix not on this lonely walk but on those joyous autumn runs when they think of him. This, they say, is the real Billy Cannon. The one they want to hold in their memory."

Teammates called each other, trying to figure out why. They'd never understood the dark places that birthed his success, and now they did not understand his failure. Did he owe the wrong people money? Did his race horses get him in trouble? Was he desperate? Did he feel above the law? Did he just not think it through? Cannon never has offered an explanation, except to call himself and his fellow co-conspirators the dumbest criminals ever, which only adds to his mystery. People wondered if he had an undiagnosed mental illness. What else made sense?

They all worried about his future. What would happen to him? Would he become so guarded, retreat so far into himself, that he could never come out?

Two and a half years later, his sentence halved thanks to good behavior, he returned home. Just about everything he'd worked for was gone. Other dentists stopped referring patients. Some folks in Baton Rouge were gleeful that Cannon had been knocked off his pedestal; toasts were raised to his demise. Cannon, friends believe, imagined that everyone was looking at him with disgust. Somewhere along the line, adoration for The Punt Return had been conflated with adoration of a man, and now it was confusing to everyone. Cannon seemed to feel people no longer loved him. Maybe they had never loved him to begin with. The run kept playing on radio and television, but people acted as if he wasn't the man who did it. He turned inward. "He almost went into a shell," Purvis says. "It hurt him so, so, so deeply that he avoided the public as much as he could."

Years passed. Lawsuits piled up. Cannon owed everyone money, it seemed, and almost none was coming in. He couldn't restart his life. He spent his days in his office, a reminder of what he'd been, alone, few patients, no staff, no working X-ray machine, out-of-date magazines, rust on the toilet. Almost a decade after he'd gotten out of jail, a Sporting News article, headlined "An Utter Disaster," signaled how far he'd fallen. Friends were quoted saying hurtful things about him. He felt betrayed.

One of those quoted, Paul Manasseh, came by to visit. He discovered Cannon by himself, reading the article. Cannon found the offending quote -- "It's a very depressing place. Billy sits in that office all day long, all by himself. He had to get an answering machine because of bill collectors. He never picks up the phone until he knows who it is." -- then, according to a friend of Cannon's, asked if Manasseh really said that.

Manasseh acknowledged he had.

Cannon just stared at him.

Manasseh asked whether it meant their friendship was over.

Cannon just stared.

Manasseh -- the one LSU person who'd shown up at Cannon's sentencing -- left. The door closed behind him.

They would never speak again.

The Louisiana State Penitentiary rises out of the fields at the end of the highway, tucked into a bend in the Mississippi River. It's been 14 years since Cannon sat in his dental office, alone, stewing over the betrayal, and now he walks through the front gate at Angola and everyone says hello. When he enters the main building, inmates pepper him with questions about The Punt Return. It lives on even behind prison walls.

"I saw you on TV when you made that runback and scored that touchdown," one convict says.

"My film is turning yellow," Cannon jokes.

"I said, 'Look at old Billy Cannon,'" the convict says. "He can run that thing."

So how did he get here?

In 1995, nearly out of options, Cannon managed to get himself hired at Angola. Warden Burl Cain wasn't expecting much. The dental program was in shambles, with dentists seldom coming to work and prisoners unable to get appointments. Cain figured it couldn't get any worse and that Cannon had something to prove. Worst-case scenario? They had their own Heisman Trophy winner.

Cannon got right to it, firing dentists who wouldn't work, hiring others who would. First as a contractor, then as a full-time employee, he scheduled all inmates for appointments, forcing them to decline if they didn't want treatment. Cain saw all the complaints disappear. When Billy talked about his work at the prison, you could hear the pride in his voice. The standard glory-days stories and aw-shucks one-liners disappeared when he discussed the ins and outs of treatment. He began to sound less like a former legend and more like a hardworking dentist.

"The man cares," Cain says. "The inmates love him, and because they love him, he cares more and won't dare let 'em down."

Cain figured if Cannon could do that, he might be able to fix an even bigger problem: the prison's entire medical system. Lawsuits from prisoners plagued Cain -- the disorganized units couldn't work together so he couldn't provide adequate treatment to the prisoners.

"I put him over the whole hospital," Cain says. "Look, he's a leader of men. He got that whole thing organized like a team. Here we go. We got all legal and fixed up, and he went back to the dental office."

The legend of The Punt Return continued to grow outside Angola, but inside, Cannon found peace, a place to keep the lives of the man and the icon separate. "He was reclusive," Cain says. "It just made sense. Don't do interviews. Don't talk to anybody. Stay out of sight, out of mind."

The man the prisoners call "Legend" bristles at any suggestion that he's ever not known who he is or that he's had to change, but people close to him say something wonderful happened out here at the end of the road. For the first time since his arrest, Billy Cannon was a success.

"Once he got that job at Angola," Purvis says, "he began to feed off that. When he saw he could get ahold of something and start giving, start coming back, start building back, I think that was the beginning of the resurrection."

Cannon is eating in a Baton Rouge sports bar, just feet from where his Heisman Trophy is on display, when The Punt Return comes on television. He watches, amused, as patrons stop eating and cheer each broken tackle as if seeing it for the first time, never realizing the man who actually broke those tackles is just a table away. He can protest all he wants, but there no way anymore to deny the truth he didn't understand 50 years ago in that restaurant out on Airline Highway: There are two of him. Mostly, they are strangers, but the man and the icon have a responsibility to each other. The icon can't stay safely at Angola forever; he needs to take baby steps back into the world. The two Billy Cannons, it seems, are beginning to understand each other at long last.

"Where do you buy experience?" he says. "You have to live it."

Just a few years ago, Cannon voluntarily appeared in public, at a banquet for the LSU and Southern University football coaches. It was the first time he'd been out with Cain, and the warden saw how the reception surprised Billy. The most powerful people in Louisiana packed the room. Instead of funny looks or whispers, Cannon found cheering people who loved him. They probably had always loved him, everywhere except inside his own head.

Certainly, the disgrace lasted longer in Cannon's imagination than it did for the folks who wanted their hero back. They didn't need to understand him; they just needed to see him, for him to see them, so they could remember. "People in Louisiana were very anxious to forgive Billy Cannon," Dietzel says, "because it didn't match up with this wonderful thing he did."

Cannon came out gradually. He appeared at events where he knew he'd be received well, and each successful appearance led to another. It was almost as though he was desperate to make up for all that lost time. He spoke at charity functions. He signed autographs. He even gave an interview or two. As the 50th anniversary of the 1958 national title approached, his phone rang constantly. Billy Cannon found himself saying yes. He seemed to be enjoying his fame instead of needing to hide from it. The people around Cannon noticed. They saw the rough edges of his gruffness rounded off, his smile quicker to appear, a man growing comfortable with his life -- with all his life. Nobody understood why this was happening. Cannon's openness is as mysterious as his exile. Ultimately, the whys don't really matter. There are things people want to see in their heroes and, finally, as an old man, Cannon seems willing to give them what they want. He does so with a smile and a disarming story. It makes them happy and, surprisingly, at least to those around Cannon, makes him happy, too.

"I really like him," says Dietzel. "I like him a whole lot more than I did when he was younger. He's much more friendly. He is a lot more humble than he used to be. I've been to several signings with him. He carries on a very pleasant conversation with everyone who comes up. I can't imagine the Billy Cannon of yesteryear doing that. He's just become a more genuine person."

Close friend Boots Garland saw it two years ago, when members of the 1958 team got together in Natchitoches. He's spent as much time around Cannon as anyone not related to him, and he's able to read his moods, spot the storm clouds rolling in. Cannon signed all night, and just when he thought he was done, someone showed up with an entire box of stuff. Garland figured an eruption was coming. He watched, amazed, as his friend smiled and signed every last thing. In the car back to the hotel, Garland turned to Cannon and said, "Big boy, you ain't bad."

"That's when it dawned on me how well he'd adjusted to being Billy Cannon," Garland says, "and the obligation he had."

The effort paid off. Once Cannon opened himself up, so many things came back to him. Twenty-five years after revoking his membership, in 2008, the College Football Hall of Fame elected him again. In late November, he walked onto the field at Tiger Stadium. His family had told him he was being honored at halftime for his re-induction. They had lied.

After a short presentation for the Hall of Fame, the public-address man turned everyone's attention to the southeast corner. A black drape fell to reveal Cannon's No. 20, forever looking out on the field where he made his run. The rumble started at the top of the upper deck, and by the time it reached the field, the old stadium shook. The announcer used the same words from so many years ago -- "Billy Cannon … Great All-American" -- and the crowd got louder. The roar would make the hair stand up on your arm.

There was poignancy in the crisp fall air, and redemption and forgiveness, too. But there was also order: This was how the story of The Punt Return was supposed to end. Cannon played his role, and the fans played theirs. Everyone felt the love in that stadium. The fans, his friends, his family. The people stood and screamed and clapped, and down near the end zone, Billy Cannon stared up at them, the mass of blurry colors and noise. He licked his lips. He swallowed hard and blinked. "Somebody told me he had tears in his eyes," Rabb would say later. "I tell you what. I've never seen tears in Billy Cannon's eyes."

Two weeks later, Cannon and his family flew to New York for the Hall of Fame celebration. The Southeastern Conference threw him a party in a fancy Manhattan hotel. Cannon acted blasť about recognition, but when I arrived at the ballroom early, I found the doors locked and one guy waiting to get in -- Billy Cannon. "This ain't me," he insisted, ever a contradiction.

Later, bouncing from party to party, he seemed to revel in his acceptance, in the reclaiming of things he'd imagined gone forever. But his daughter Bunnie Cannon, who traveled with him, said they had worried about losing him in the Atlanta airport and was happy to have gotten him to the Big Apple at all. He'd considered not coming. "He likes his family," Bunnie said. "It's peaceful. All of this, it's very different."

At the news conference, with a room full of New York reporters in person and more on the phone, he wiped his forehead and then his hands. He sweated. This was the part his family worried about. What if all anyone cared about was his conviction? What if it ruined the entire trip for him?

Instead, predictably unpredictable, Cannon brought up his past himself. "You should be happy you didn't have to be elected twice," he said.

Only a few people laughed, but there was something wonderful about the silence. The joke fell flat, but only because people didn't get it. Some didn't remember. Others didn't care. They weren't seeing a disgraced legend, just someone who had won the 1959 Heisman Trophy thanks to the most famous punt return in football history. The schism of the moment and the man was over.

When the news conference was finished, Cannon noticed an Associated Press reporter lingering, the poor guy whose job it was to ask an old man about the worst thing he'd ever done. Now, Cannon might be a lot of things, but he's no dummy. He knows no news story about him can ever run without something about the counterfeiting. So instead of hiding from his past, he confronted it.

"The people of Louisiana are quick to love," Cannon told the AP guy. "They are also quick to forgive."

When the reporter asked the question, Cannon said, "I did the crime and I did the time. I haven't had a speeding ticket since."

And that was it.

"You ready?" his wife, Dot, asked.

"I'm ready to eat," he said.

They walked out of the hotel together, headed to lunch, two generations in tow. It hadn't been easy, but Billy Cannon seemed to have emerged from his ups and downs mostly intact.

"I haven't lost anything," he says. "My family loves me."

He uses the word "beautiful" a lot these days. He laughs even more. A few weeks ago, he called Garland. He wanted to know the height of a goalpost and the thickness of a crossbar.

"Why?" Garland asked.

It seems Cannon was trying to figure out whether he could have dunked a football over it in his prime. These are the things that take up the spare time of a Louisiana legend. He hangs out with Dot and plays with his horses and looks forward to the holidays when his home fills up with grandchildren. "My old daddy had a saying," he says. "It's not how high the peak or how low the valley. It's how far across this valley we're in. Think about that sometime before you go to bed at night. It's not how high or how low. It's how far across."

There is a balance now. He goes to all sorts of public events. He makes jokes about his stint in prison; at a press event not long ago, he looked at the tape recorders and cracked, "The last time I saw those, the FBI was in town." He goes to LSU games, with grandchildren in tow, and he loves it when The Punt Return is played on the video board, not to watch himself run but to watch the faces of the little ones, see their eyes widen with each broken tackle, as the stories they've heard about their granddaddy become real. He enjoys that time, but he won't let it consume him, just as there are parts of himself he will not share with the world. He's seen the nature of public adoration, how it's fickle, how it's more about moments than men. He guards the places in his life that might solve the mystery he presents to the world. More than a year ago, when I asked whether I could come see his horses and his house, he snapped that he didn't want anyone there. His horses are private. His home is private.

He knows he's an enigma to many -- "I think I'm pretty self-aware," he says -- and he uses that to protect himself. He cultivates an image of floating above his own legend; when he let the sports bar display his trophy, he asked the guy picking it up to fib and tell reporters they found it beneath an old oil-cloth in the garage, which he did, which became another chapter in the myth. There is utility in his persona, value in the way he interacts with the world. "I'm a little gruff with people I don't know and don't know what their ulterior motive is and don't know what the want," he says. "Or what they want you to do for them. I'm a little gruff and defensive. It works. Because they will keep their distance."

His antenna about people -- the thing that got him into so much trouble for much of his adult life -- is more finely tuned now.

"There was times right when I got out of school when everybody was a friend and everybody was a good guy," he says. "After a while, you say, they're not friends and they're really not good guys. Now how much did it cost you to make that decision? Sometimes more than you want to talk about."

That's his journey. He's a 72-year-old man sitting in a white rocking chair outside the main gate of Angola. The sky is huge, the air hot and muggy, just like Halloween 50 years ago. That night still hangs around him, as if dawn only just took it away. The legend is his life, the broken tackles, the Tiger Stadium roar, the adoring restaurant, all of it. Cannon still remembers The Punt Return. He ran so fast it was a blur. Run toward your colors and away from theirs. That's what he kept telling himself as he headed toward the sideline.

The first time he saw the replay, more than a dozen years after the run, something seemed off. Then he realized: He remembers it in color.

His vision of his own life has always held little in common with the people who clamor to know him. When presented with evidence that he's changed, he just smiles and insists that he's always known who he is. He is man who ran through tackles. He is a man who survived five heart bypasses and cancer. He is a man who made millions of dollars of fake money and never really explained why. He is a man who spent years avoiding the public, then, suddenly, handled it with ease. He can be surrounded by people, yet remain alone inside his own mind. He was born a mystery, and he remains one.

He stands up from the rocking chair. He's like a puff of smoke when he wants to disappear, just gone, a memory. He's headed home to his beloved horses. He feels safe with them. He likes to groom them alone, to watch them work their muscles. Horses can't be known; they can only be watched with awe. They don't have pasts or futures. They only have the run. They are at peace at full speed, the world around them a blur. Sometimes horses win every race and pass gracefully into old age. Sometimes even the best horses break down.

"I've been there, done that," he says. "I know what it is to be the horse."

Join the conversation about "The Redemption Of Billy Cannon."

Wright Thompson is a senior writer for ESPN.com and ESPN The Magazine. He can be reached at wrightespn@gmail.com.